Eric Franklin Wood, a world-renowned hydrologist who did groundbreaking work in drought prediction and served on the Princeton faculty for 43 years, died from cancer in Brooklyn, New York, on Nov. 3. He was 74.

Eric Wood, 2017

Wood, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering(Link is external) (Link opens in new window), Emeritus, pioneered research in hydrology, remote sensing, climate and meteorology. He also led the Terrestrial Hydrology Research Group, which investigated land-atmosphere interactions for climate models and for water resource management. He was considered a visionary who shed new light on the role of water in the climate system and developed innovative analytical tools.

Wood was also known for his large and influential research group at Princeton, serving as a mentor to more than 30 Ph.D. students, plus more than 30 postdoctoral researchers and staff.

“He was a giant in the field. He had a tremendous impact on the profession and certainly in the department at Princeton,” said Michael Celia, the Theodora Shelton Pitney Professor of Environmental Studies and professor of civil and environmental engineering. He noted that Wood was instrumental in developing the department and the Water Resources Program.

Wood was born in Vancouver, Canada, in 1947. He earned his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the University of British Columbia in 1970 and his doctorate from MIT in 1974.

After two years in Laxenburg, Austria, as a research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Wood joined Princeton’s faculty in 1976. He transferred to emeritus status in 2019, continuing to develop hyper-resolution land surface models.

Early in his career, Wood worked on groundwater hydrology but then shifted to examining hydrologic atmospheric interactions in the evaporation of water and how that fits into the climate cycle.

“That was a relatively new field, and kudos to him that he identified it early on as something that would be of interest,” said Peter Jaffé, the William L. Knapp ’47 Professor of Civil Engineering.

Wood was also a pioneer in developing spatially distributed hydrologic models of watersheds to account for the effects of topography. He introduced the concept of a “representative elementary area” and quantified the minimum area needed to resolve watershed hydrologic response.

Wood’s work tackled practical problems, such as the field work he did at the Love Canal hazardous waste site in Niagara Falls, New York. Wood designed a soil sampling protocol that would enable the Environmental Protection Agency to decide whether the land could be resold and people could move back in. Wood took a lead role in planning for the NASA Earth observing system satellites, and he was part of the first team that proposed a soil moisture observation mission, opening up satellite remote sensing as a source of valuable data in the field of hydrology.

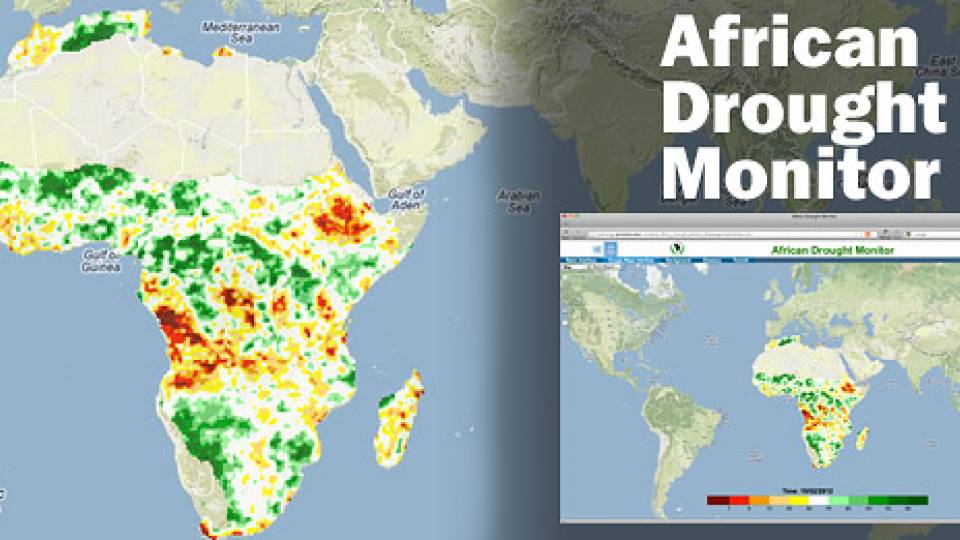

Around 2010, Wood proposed the development of hyper-resolution land-surface models with spatial resolution smaller than 100 meters, which could be applied at continental scales. The approach enabled discovery of patterns of river flows, floods and drought at scales ranging from regional to global. In 2017, in recognition of these advancements, Wood was awarded the American Geophysical Union’s highest honor in hydrology, the Robert E. Horton Medal for “major advances toward process-based representation of global hydrology.” It was one of 17 major awards Wood received over the course of his career. He also was elected to the National Academy of Engineering.

Wood developed large-scale hydrologic models to link measurements of soil moisture content from satellites and airplanes to activity deeper underground for an overall mass balance of water.

“He [studied] desertification, how changes in atmospheric conditions and ground-soil moisture translated to desertification, and, in that field, he became one of the top leaders,” Jaffé said.

These interactions of land, atmosphere and water are proving to have major repercussions on water supplies in a changing climate.

“He worked on important problems, not only scientifically interesting ones,” Jaffé said.

Wood, his students and co-researchers developed unique databases for large-scale hydrology models often used by other researchers.

Justin Sheffield, one of Wood’s longtime co-researchers and head of geography and environmental science at the University of Southampton, England, said Wood had great insight into the major issues that defined water use on a global scale.

“Eric made a tremendous impact on the field of hydrology through his group’s research at Princeton over 40 years, including fundamental advances in how we observe, model and understand the global water cycle,” Sheffield said. “Perhaps more importantly, he pushed the international research community to collaborate on some of the biggest water-related challenges under global change.”

Wood had a very active and large research program that attracted significant external funding, boosting visibility for the department and University in the field of hydrology.

Mark Zondlo, who joined the department in 2008 and is now a professor of civil and environmental engineering, recalled being immediately impressed by Wood’s group. “His group meetings were the size of a faculty meeting,” Zondlo said. “It was the epitome of what I wanted my research group to be.”

Wood mentored Zondlo, now the department’s director of graduate studies, and emphasized the importance of graduate students because of their creativity, intelligence and openness to new approaches to problems. Zondlo recalled that Wood often advised listening closely to younger researchers, saying “graduate students take you to new places.”

Even this past summer, as his health declined, Wood was lobbying to be part of an upcoming faculty seminar.

“That says a lot about who he was,” Celia said. “He had this incredible dedication to what he saw as his craft, and right up until the end, he wanted to be able to get up and talk about the work he was doing that he felt strongly about.”

Kaiyu Guan, a 2013 graduate alumnus in environmental engineering and an associate professor in ecohydrology and remote sensing at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, remembers a hydrology class he took with Wood; Guan was the only student registered. All semester, Wood stood in the front of the classroom, drawing on the blackboard and lecturing passionately for an audience of one.

Guan said Wood could be tough but that the work in what turned out to be a one-on-one seminar gave Guan a deep understanding of the field, and their shared interest led to a strong bond. Guan went on to collaborate on several more projects with Wood while at Princeton.

Guan said Wood hated fake science and disliked people doing superficial things. But his attitude was instrumental in training students to be creative and independent thinkers. Guan called Wood his “academic father.”

“He gave students space to be independent, to think, to come up with their own ideas. He purposefully didn’t give you the answer. He gave you hints and guided you. He was patient,” Guan said. “He really wanted to give you the space to think for yourself. We are always proud we were trained by Eric, that we were Eric’s students.”

Outside the classroom, Wood loved the outdoors. His devotion to fishing was legendary, as the professor would invite colleagues to his house to sample large quantities of cured and smoked salmon he had caught. “When he didn’t talk hydrology, he often talked fishing,” Jaffé said.

He is survived by his siblings John Wood, Elizabeth Wood and Peter Wood; former spouse Katharine Wood; his children, Alex Wood and Emily Wood; and his grandchildren Clementine Crouch, August Wood, Elliott Wood and Silas Wood.

View or share comments on a blog(Link is external) intended to honor Wood’s life and legacy.