If immigrants to the United States formed their own country, their pre-COVID-19 life expectancies would exceed or match those of the world’s leaders in longevity — Swiss men and Japanese women.

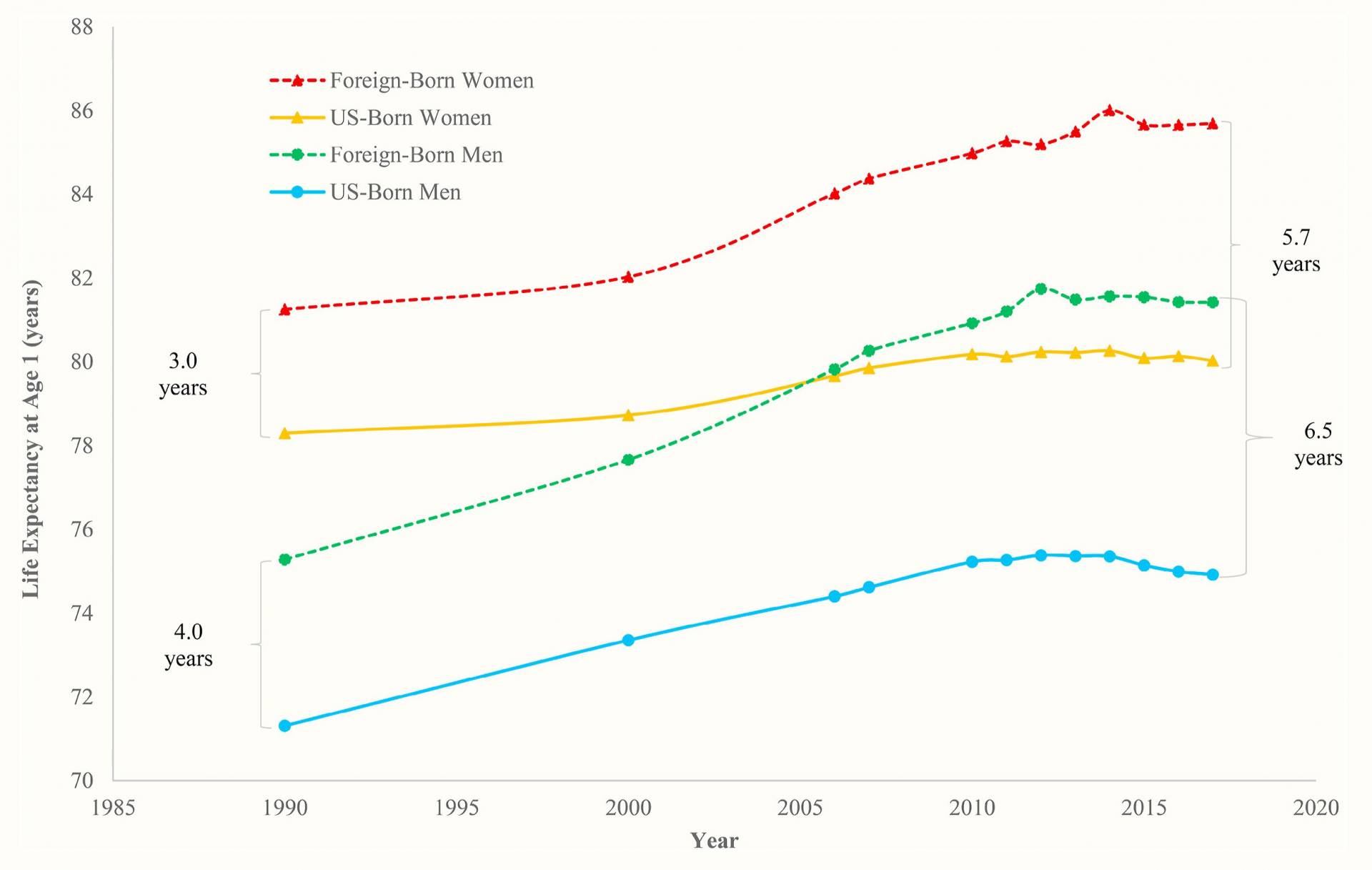

A new study by Princeton University and University of Southern California researchers estimates that immigration adds 1.4 to 1.5 years to U.S. life expectancy at birth. In 2017, foreign-born life expectancy reached 81.4 and 85.7 years for men and women, respectively. That’s about 7 and 6.2 years longer than the average lifespan of their U.S.-born counterparts.

“Demographers knew that immigrants lived longer. The main question that we set out to answer was, ‘How much is this really contributing to national life expectancy trends?’” said Arun Hendi, the lead author of the study and an assistant professor of sociology and public affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. “Our results show that they're making an outsized contribution to national life expectancy.”

The study was published in the September 2021 issue of SSM Population Health, by Hendi and Jessica Ho, an assistant professor of gerontology and sociology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. Their work provides new insights on how immigrants contributed to national life expectancy trends over nearly three decades, from 1990 to 2017.

The research suggests that immigrants are responsible for approximately half of the recent U.S. gains in life expectancy. Moreover, the gap in life expectancy between foreign-born and native-born residents is widening.

In fact, the researchers say, Americans’ life expectancy would steeply decline if it weren’t for immigrants and their children. Under that scenario, U.S. life expectancy in 2017 would have reverted to levels last seen in 2003 — 74.4 years for men and 79.5 years for women — more closely resembling the average lifespans of Tunisia and Ecuador.

Diverging trends during the last decade

Prior research has shown that between 2010 and 2017, overall U.S. life expectancies saw an unprecedented stagnation. The plateau has been largely attributed to drug overdose deaths among adults in their prime working ages and slowdowns in the rate of improvement in cardiovascular disease mortality. But this new study shows that immigrants experienced life expectancy gains during this period, while the U.S.-born population experienced declines.

“If it weren't for immigrants, our national life expectancy stagnation that we experienced since 2010 would instead be a national decline in life expectancy,” Ho said. “For them to have that large an impact is unexpected because they represent a relatively small proportion of the U.S. population.”

In addition, while the immigrant advantage was already present in 1990, the research shows that the difference between immigrants and the U.S.-born has widened substantially over time, with the ratio of American-born to foreign-born mortality rates nearly doubling by 2017.

“When compared to immigrants’ life expectancy, the U.S.-born are doing poorly. Much of this is related to their very high mortality at the prime adult ages,” said Ho, an expert in the social determinants of health and mortality. “Low mortality among prime-aged immigrants doesn’t just help the foreign-born — it helps the U.S.-born too. Prime-aged adults are likely to be in the labor force and raising children. This means that they contribute to higher tax revenues and slower population aging.”

Hendi says this is particularly relevant today because those prime adult ages are where the country is losing years of life due to drug overdose mortality and other preventable causes of death.

“The fact that immigrants are doing well suggests that there is a capacity to thrive in the U.S., but the U.S.-born aren't fulfilling that potential,” he said.

Life expectancy at age 1 by sex and nativity, 1990–2017. The gaps between the foreign-born and US-born life expectancies in 1990 and 2017 are indicated by brackets, with gap values adjacent to the brackets.

Immigrants a small but influential share of the U.S. population

Immigrants make up under 15% of the U.S. population, up from around 8% in 1990 but still a small percentage of the total. Hendi and Ho cite healthy behaviors and the changing selectivity of the immigrant population as factors that may contribute to their influence on total life expectancy.

“Immigrants tend to be healthier in part due to the selective migration of those who have the health, resources and stamina to migrate to the U.S., and this selectivity may have grown stronger,” Ho said.

The researchers highlight the role of increases in high-skilled immigration, which is partly reflected in changes in countries of origin as immigrant streams shift from Mexico to places like India and China. They also note that there may be pro-longevity characteristics of immigrant populations, regardless of country of origin, including a lower propensity to drink, smoke and use drugs than U.S.-born residents.

“Many of America’s immigrants come from lower-income, less-developed nations, leading some to worry that these immigrants bring their home countries’ high-mortality conditions with them and thus drag down America’s national average longevity,” Hendi said. “But the results say just the opposite. Far from dragging down the national average, immigrants are bolstering American life expectancy. A big part of the story appears to be that immigrants take fewer risks when it comes to their health.”

The study additionally found that the children of foreign-born residents retain some life expectancy advantage but do not fare as well as their parents.

Hendi and Ho used data from the National Vital Statistics System and the U.S. Census Bureau to estimate life expectancy levels among foreign-born, U.S.-born and total populations between 1990 and 2017.

The team plans to examine COVID-19's impact on immigrant life expectancies. A January 2021 study by USC and Princeton researchers found the COVID-19 pandemic had significantly affected life expectancy, with stark declines in life expectancy among Black and Latino populations. A separate USC study last July of a large diverse group of Medicaid enrollees found Latino patients had starkly higher odds than whites of testing positive for COVID-19 as well as higher odds of hospitalization and death.

This work was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants R00 HD083519 and P2C HD047879) and the National Institute on Aging (grant R01 AG060115) at the National Institutes of Health.