Students in the spring 2021 course "Archiving the American West" honed their primary research skills, while also learning about the history and contemporary politics of archives and special collections. Pictured: San “Sanatorium” children. Katharine Kilbourne Photograph Album of Jicarilla Apache Boarding School, Dulce, New Mexico, 1931.

Archival materials tell the stories of people from the past — their experiences, struggles and heartache.

But who determines the contents of an archive? How do a library’s holdings influence historians? Whose stories get told and whose do not?

Students in the spring 2021 course “Archiving the American West,” taught by Martha A. Sandweiss, professor of history, in collaboration with Gabriel Swift, curator of Western Americana, and Brian Wright, Ph.D. candidate in history, explored these questions by engaging with Princeton University Library (PUL)'s Collections of the American West.

Sandweiss, Swift and Wright designed the course to not only hone students’ primary research skills in Western American history, but also to teach about the history and contemporary politics of archives and special collections.

“Archives are created by people with points of view,” Sandweiss said. “I wanted students to gain a real sense of the politics.”

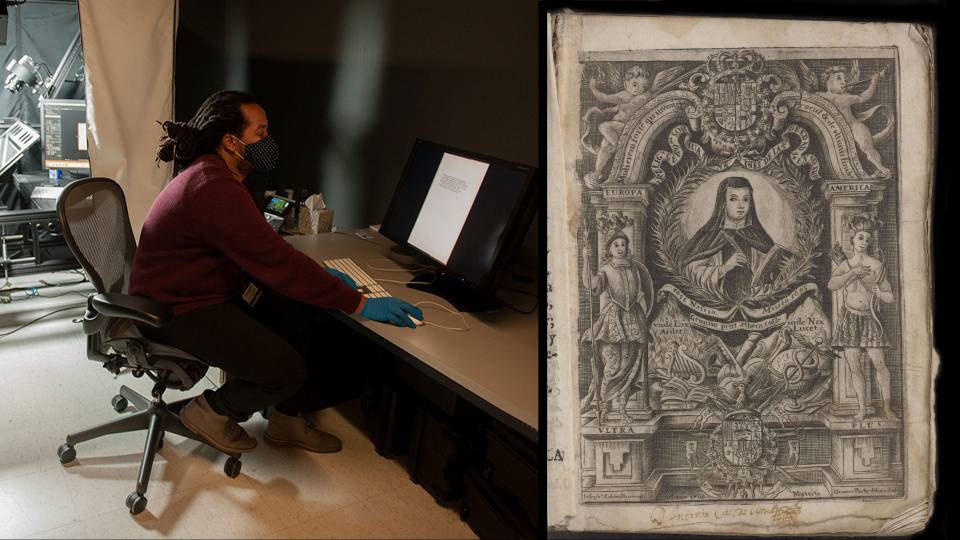

Originally conceived as an in-person course, the COVID-19 pandemic compelled the class to pivot to an online format. PUL staff generously fast-tracked the instructors’ voluminous digitization requests, and by the first week of class had digitized more than 850 photographs and 2,000 pages of manuscript material for the students’ study.

Student assignments included writing a research paper analyzing a recent PUL acquisition and developing a proposal to purchase archival items with library funds that would expand the diversity of Princeton’s holdings (an experiment which successfully led to numerous acquisitions). The students also created an online exhibition of un- or under-cataloged pieces documenting the American West.

“We wanted to empower undergraduates to discover and document something — or perhaps everything — about objects and documents that were little-known or unknown to historians,” Wright said. “Much of the material that students researched was purchased, cataloged and digitized exclusively for the course, so they really were taking a first pass at it.”

‘Stories don’t end when materials enter the archive’: The children behind the pages of a 1931 boarding school photographic album

“Archives are created by people with points of view,” said Martha Sandweiss, professor of history. “I wanted students to gain a real sense of the politics.” Pictured: Orphans at hospital. Katharine Kilbourne Photograph Album of Jicarilla Apache Boarding School, Dulce, New Mexico, 1931.

Guest speakers ranged from rare book dealers to library curators, including Princeton alumni.

One guest speaker was Dr. Yolandra Gomez Toya, a pediatrician and 1988 alumna, whose mother attended a boarding school for Jicarilla Apache children in Dulce, New Mexico, in the 1930s.

Sandweiss knew Toya lived near the area and reached out to her for ideas on how to talk about a 1931 photographic album of the boarding school held in PUL’s collections. After Toya realized her 90-year-old mother had lived in the boarding school, she agreed to record an interview with her mother for the class.

“I was a little nervous to be honest,” Toya said. “The religious, residential schools have always been difficult for our family to talk about.”

Toya’s mother, Cora Vigil Gomez, was born into a Jicarilla Apache family, probably in 1931. Gomez’s parents kept her birth a secret to hide their daughter from local missionaries. When the missionaries discovered Gomez, they came to the family’s house with police who threatened to put her father in jail if he didn’t give up his daughter. For eight to 10 years, Gomez lived at the boarding school, seeing her parents only a few times each year.

“Whenever my mom talked about the school, she’d say they were the loneliest years of her life,” Toya said. “It’s still very painful.”

Toya interviewed her mother in person in March 2021, after not seeing her for an entire year due to the pandemic. COVID-19 has hit Native American populations very hard, Toya said. Communities lost many Native speakers.

Toya’s mother was able to identify many of the teachers and students in the photo album, including a little boy who would die of tuberculosis, a girl who would marry a trader and another boy who would leave the reservation.

“It was a conversation that needed to happen,” Toya said. “It’s not talked about enough. These boarding schools were part of the systematic destruction of our language, our culture and our people. We’re still feeling the ramifications in our communities today.”

Many non-Natives “view us as historical artifacts,” with a romanticized view of spirituality, teepees and art, Toya said. “They don’t realize that we’re human. We live and breathe the same air. Today I’m wearing scrubs and tennis shoes.” She expressed her view that education needs to happen “with open hearts and minds.”

Toya’s work as a pediatrician follows her family’s lineage of healers. Her mother became one of the first female tribal council leaders, while raising 10 children with her Hispanic husband.

Sandweiss recognizes the responsibility that libraries and institutions have to connect archival materials with the communities from which they came. “These stories don’t end when materials enter the archive,” she said. “They’re continuing to unfold. History matters. People in Dulce still live there.”

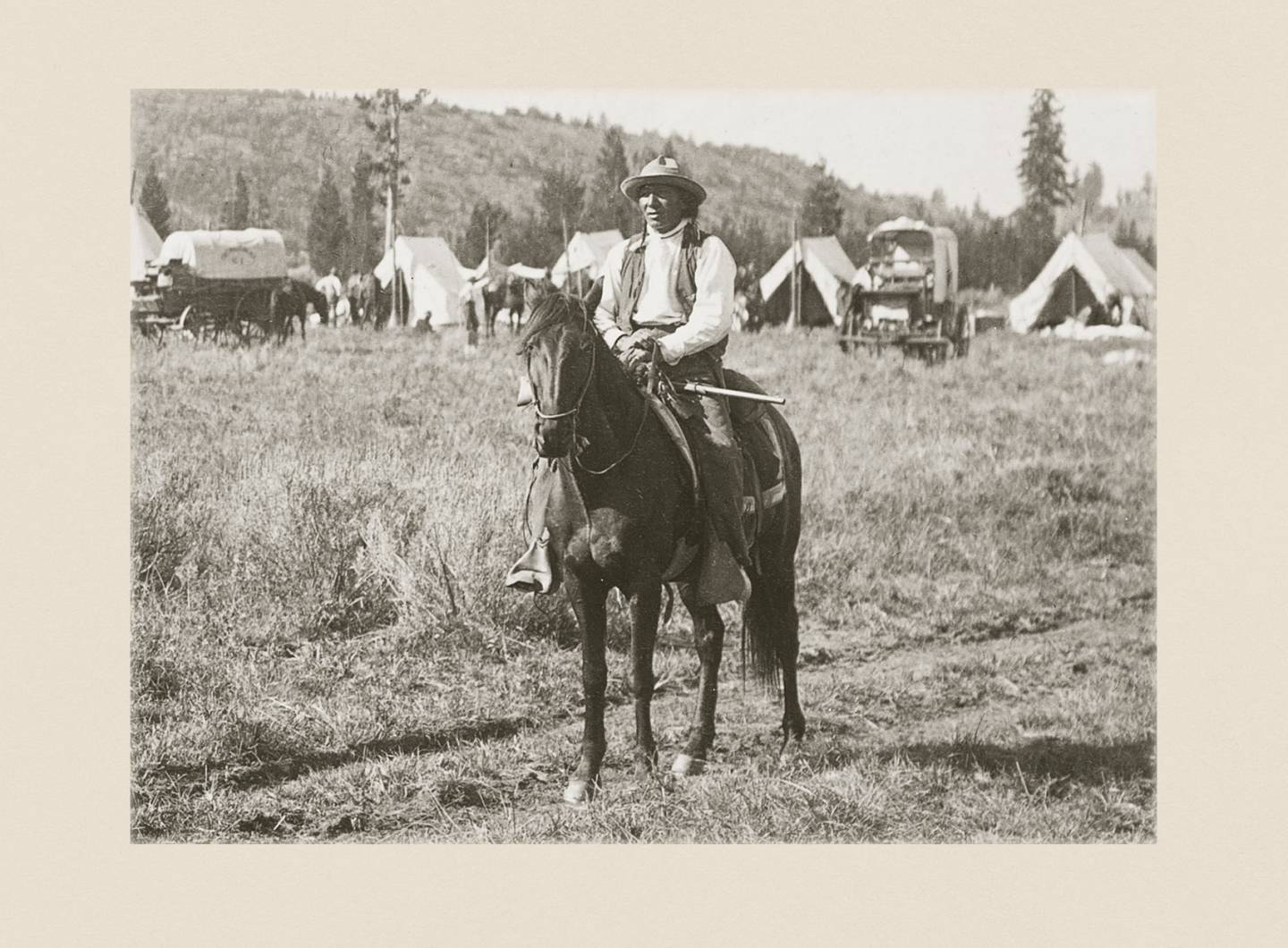

Untold stories and historical erasure: Grant Short Bull

Students developed proposals to purchase archival items with library funds that would expand the diversity of Princeton’s holdings and created an online exhibition of un- or under-cataloged pieces documenting the American West. Pictured: Grant Short Bull, pictured on horseback during the Webb hunting expedition. Bare Outlines of a Brief Trip to the Jackson Lake Country in Northwest Wyoming, 1896. Original photo by F.J. Haynes.

Noa Greenspan, a member of the Class of 2023 and an English concentrator, learned firsthand the importance of stories while researching her final project. She analyzed two photographic journals documenting an 1896 expedition into Yellowstone National Park. [Read her essay online.]

An itinerary in one of the journals listed everyone on the trip, but included only the last name of the guide, “Short Bull.” Two men, Arnold and Grant Short Bull, were born around the same time and were conflated in historical records.

While searching for more about these men, Greenspan found a website by Arthur Short Bull, who has been researching his great-grandfather, Grant Short Bull, a member of the Oglala Sioux.

Greenspan called Arthur to put together the pieces. “He had so much information to teach me,” she said.

For Arthur, the 1896 expedition was new information, but he noted that his great-grandfather’s role made sense, given his military position and knowledge of Wyoming’s land.

Greenspan recorded her conversations with Arthur (available through the online exhibition), who spoke about historical erasure and America’s complicated past and present.

Regarding Yellowstone, Arthur said: “The only positive thing I can say about national parks is that at least they keep [them] pristine in some cases. I enjoy that, because that shows me that at one time, this country was a beautiful place to be. But at the same time, my entire life I’ve always had problems with people claiming territory that does not belong to them.”

The future of the archives: Diversifying narratives

Swift said that the assignment in which students identified materials from underrepresented subjects brought several exciting and diverse pieces to the library’s collections. Every student in the class found material that was acquired by PUL.

Jacquelyn Davila, a member of the Class of 2022 and a history concentrator who is also pursuing a certificate in Latin American studies, examined Mexican American food in the American West. “In thinking about the West and the long history of Mexican people in this region of the United States, I did not want to think of Mexican American food as a product of just Mexico or the U.S., so I built an archive that was both regional and transnational,” she said.

Davila uncovered “El Cocinero Mexicano" [The Mexican Chef], a cookbook that was emblematic of Mexican cuisine, published in Mexico City in 1831 right after Mexican independence. She said she selected this book for PUL to purchase not only because of “its importance in asserting Mexican national identity, but also because a lot of its recipes would appear in Encarnación Pinedo's 'El Cocinero Español' [The Spanish Chef], which showed the transborder/transnational nature of this regional food culture.” Published after “The Mexican Chef” in 1898, “El Cocinero Español” is considered to be the first Mexican American cookbook ever published in the U.S.

“Many of Pinedo's recipes appear to have been directly influenced by “El Cocinero Mexicano,” Davila said. “However, as was commonly done at the time by Anglo Americans and Mexican Americans alike, Pinedo strategically chose to label her cookbook as ‘Spanish.’"

Davila found a pamphlet of recipes printed by the USDA, published on the East Coast in 1917 during World War I. “The pamphlet was government propaganda trying to convince housewives that cooking cornmeal is patriotic,” Davila said.

These items tell the story of a century of transformation, “from the elite who viewed Native American food as inferior to European food, to a pamphlet encouraging women cook tamale pies as an act of patriotism,” Davila said.

Growing up in Sacramento, California, Davila said: “The type of history I learned revolved around the Gold Rush. As children, we dressed up as settlers in Sutter’s Fort and heard the narrative of the 49ers. ... This course made me question the archives and their role in historiography, not just how archival silences and sources shape scholarship, but also how public history plays out in people’s collective memory.”

Some students expressed interest in future collecting pursuits and curatorial careers.

“The course showed me a lot about the different careers in this field, from what Gabriel [Swift] does at Firestone [Library], to people who are in the bookselling business,” said Katie Bushman, a member of the Class of 2022 and a history concentrator.

Bushman visited PUL’s Special Collections several times during the semester for the course and for her junior paper. “Holding the letters and diaries, written by people in the past, makes history feel so real,” she said. “It connects us to the human side of the past.”

This story is part of PUL’s Teaching with Collections series.