Six Princeton professors talk about how the books on their shelves relate to their work and share what’s on their summer reading lists. Some book choices reflect their scholarly research and teaching. Others illuminate personal interests and current issues in the headlines. And with a hat tip to the quarantine-induced popularity of audiobooks and podcasts during the pandemic, they include audio selections as well.

Read about the professors’ choices below.

Katie Chenoweth(Link is external), associate professor of French and Italian(Link is external)

Katie Chenoweth

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

I sometimes joke that I only ever read one book: Montaigne’s “Essays.” It is a 1,000-page text from the French Renaissance, which proposes to take the author himself as the “matter of [his] book” — a radically original project in the 16th century. I do scholarly work on Montaigne, but I also read the “Essays” just for myself. I have a dozen copies in my office in French and English that I use for teaching, but I have another five or six copies at home. The filmmaker Orson Welles once said that he would read a few pages of the “Essays” every week (“like other people read the Bible,” said Welles), and Montaigne said he read his favorite books in the same punctuated, haphazard way, “without order and without plan, by disconnected fragments.” That’s how I like to read the “Essays,” too, over the summer or any time. The “Essays” lend themselves to this kind of reading because the massive book is divided up into many chapters, some of which have weighty philosophical titles like “Of Experience” or “Of Vanity,” while others take up subjects like thumbs, smells or cannibals. There’s no plot to the “Essays,” or even an argument: it’s an organic investigation of what it means to live, think and write.

It’s also a book that explores the extreme heterogeneity of human culture and experience, decentering any Eurocentric perspective and even any anthropocentric perspective (Montaigne famously wonders whether his cat might not be playing with him, instead of the other way around). Ultimately, it’s a reflection on how difficult it is to know anything — even, or especially, ourselves. I go to Montaigne for the pleasure of his writing and his company, but also for the power of this skeptical attitude, which feels to me like an important counterbalance to the many dogmatisms of our world.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

For my research, I’m spending most of my time tackling the monumental works of Montaigne’s favorite author, Plutarch: the “Moralia” and the “Parallel Lives.” I’m also revisiting “Specters of Marx” by the Franco-Algerian philosopher Jacques Derrida, written in 1993 — just after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Derrida’s approach is to read Marx alongside “Hamlet,” focusing on the ghost of Hamlet’s father and the famous line “the time is out of joint,” to propose an ethics and politics of what he calls “spectrality”: a coming to terms with ghosts, that is, what is not fully alive but also not entirely dead. After a year when time has felt distinctly “out of joint,” when the political ground has shifted under our feet, I think “Specters of Marx” makes for very (un)timely reading.

I’m also a huge podcast listener. My summer rotation includes:

- “Higher Learning(Link is external),” a bi-weekly podcast about Black culture and politics, hosted by Van Lathan and Rachel Lindsay, which is educational, unflinching and often very funny;

- “The Trials of Frank Carson(Link is external),” a fascinating and superbly reported true crime podcast from the Los Angeles Times, which looks at a striking case of injustice and abuse of power in the justice system; and

- Season 1 of “Gangster Capitalism(Link is external),” a riveting account of the 2019 college admissions scandal that also asks important questions about how we — parents, students, educators — collectively think about college and the college admissions process.

Ruby Lee, the Forrest G. Hamrick Professor in Engineering, and professor of electrical and computer engineering(Link is external)

Ruby Lee

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

I just finished the book “Strength in What Remains” by Tracy Kidder. This is a compelling story of a young man who escaped the genocide in Burundi, Africa, and his sojourn in Manhattan from sleeping in the park to medical student. The inexplicable racial hatred in Burundi and Rwanda is clearly and graphically depicted, as well as the inhospitable environment of New York City for earnest but destitute newcomers. Also, the book shows how individuals, in Africa and America, who help others in need, can make a huge difference in their lives and, indirectly, the lives of many others.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

In addition to reading Ph.D. theses on security, deep learning and computer architecture, my reading these days is actually listening to audiobooks on audible.com — often as nice bedtime stories. The books on my summer list are:

- “Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship and Purpose” by Joe Biden

- “Where the Light Enters: Building a Family, Discovering Myself” by Jill Biden

- “Madame Bovary” by Gustave Flaubert

- “A Woman Makes a Plan: Advice for a Lifetime of Adventure, Beauty and Success” by Maye Musk

- “The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect” by Judea Pearl and Dana MacKenzie

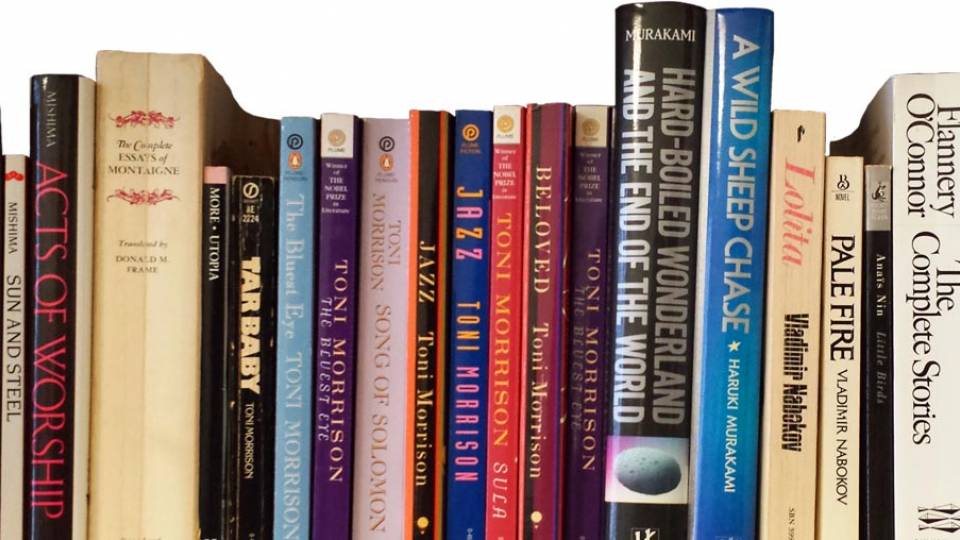

Paul Nadal(Link is external), assistant professor of English(Link is external) and American studies(Link is external)

Paul Nadal

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

“The Filipino Rebel” (1930) by Maximo M. Kalaw is an exquisite literary artifact. One of the first novels in English written by a Filipino, it restages the independence debates of the 1920s, allegorizing the rise of anti-colonial resistance against the background of the transfer of colonial power from Spain to the United States. Kalaw’s novel, subtitled “A Romance of American Occupation in the Philippines,” is, unfortunately, not easy to get hold of — I could track down only two physical copies of the first edition, one at Cornell University, the other at the British Library. The good people of Princeton Library’s Interlibrary Loan(Link is external) office helped to procure one of them on my behalf.

I am completing a draft of my first book, which uses an economic phenomenon, “remittances” — the money that migrants send home — as a framework to trace the transpacific itineraries of 20th-century Philippine literature. Kalaw’s novel seems to me a paradigmatic example of “remittance fiction” in that it is an imaginative work borne out not only by migration — the author, under a colonial scholarship program, earned bachelor’s degrees from the University of Washington and Georgetown University and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan — but also by a certain interdisciplinarity avant la lettre. Kalaw was first and foremost a political scientist, but he turned to novel writing to pry apart his moment’s political vocabularies — “education,” “revolution,” “government,” “freedom” — in a way that he could not with political treatises (and indeed he wrote many). It’s impossible for me to read this political novel without the author’s American training in mind, and I am fascinated by Kalaw’s place on the threshold between Philippine and American literature.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

During the summer I continue to read work related to finance, colonialism and the global novel; I also gravitate to the wily, the mercurial, the passionate, the essayistic. Some favorites this summer are:

- “Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery and the Philosophy of History” by Ian Baucom

- “Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said” by Timothy Brennan

- “We Do This ’Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice” by Mariame Kaba

- “Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization” by Achille Mbembe

- “The Committed: A Novel” by Viet Thanh Nguyen

- “Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music” by Alex Ross

- “Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico” by Juan Villoro

I am learning Spanish, so also on my summer list are Jose Rizal’s two novels, “Noli Me Tángere” and “El Filibusterismo.” Rizal is a giant of Philippine literature, and I have read those novels many times in English — but it gives me a new type of pleasure to make my way through them in the original Spanish.

On my long afternoon walks with Goji, my rambunctious three-year old French bulldog, I listen to “Novel Dialogue(Link is external),” a new podcast which pairs a novelist with a critic “about how novels are made — and what to make of them.”

Eldar Shafir(Link is external), the Class of 1987 Professor in Behavioral Science and Public Policy, and professor of psychology(Link is external) and public affairs(Link is external)

Eldar Shafir

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

From books on my shelf, I’m going to pick “Humanity,” by the philosopher Johnathan Glover. It mostly addresses the brutal history of the 20th century, but to me it captures something deeper, that is central to my academic interests, namely, our capacity to be intensely loving and stunningly cruel, deeply compassionate and profoundly indifferent, amazingly clever and so damn stupid. In my course “The Psychology of Decision Making and Judgment,” which I am again teaching this fall, this is a frequent tension: Students arrive from disciplines like economics, where agents are terribly sophisticated, and they encounter us, often numb, myopic and confused.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

I’ll be teaching a Freshman Seminar this fall, “The Human Context,” where we’ll explore the under-appreciated power of context and contemplate ways it might be made more conducive to human thriving. Context plays a big role in the behavioral and social sciences: it shapes who we are and what we do in ways that we fail to recognize. It’s the water in which we swim. Beyond obvious features, like climate or wealth, the human context includes less apparent features like inequality, discrimination, social norms, societal narratives, and the law. A lot of my reading this summer (yes, I probably will never make it through the ambitious list below) is tilted towards these contextual factors.

I hope to read Ibram X. Kendi’s “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America,” and Eric Klinenberg’s “Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization and the Decline of Civic Life.”

Also, “Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning,” where historian Timothy Snyder considers the very human, and recurring, socio-political contexts that lead us to unthinkable atrocities. And Linda Gordon’s “Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits.” Lange, a witness to the Great Depression, contemplated how hard it was to photograph a proud man in a context of utter poverty, “because it doesn’t show what he’s proud about.” Lange struggles with how to get the camera to register things about her subjects that are more important than their poverty — their strength, their spirit. Hopefully, also “A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion,” where Fay Bound Alberti examines loneliness (which is correlated with homelessness and other forms of marginalization) and distinguishes between context and mental state — between being alone and feeling lonely.

I just read a great novel called “Apeirogon” by Colum McCann. The book centers on the real-life friendship between two fathers, a Palestinian and an Israeli, who are brought together after losing their daughters, Abir Aramin, age 10, and Smadar Elhanan, age 14, to the violence of the Middle East. A book on my list for this summer is “The Girl Who Stole My Holocaust: A Memoir” by Noam Chayut, a member of Breaking the Silence, a group of Israeli veterans who expose and decry the impact on young soldiers of serving in a context where you control and humiliate a civilian population on a daily basis. Chayut dedicates the book to the memory of Abir and Smadar.

In an ideal world (i.e., probably not this one), I would also get to Mark Carney’s “Value(s): Building a Better World for All.” Carney, a celebrated central banker, contemplates our disastrous misplacement of value — status, responsibility, wellbeing — in financial markets (a major ingredient in the water in which we currently swim).

Judith Weisenfeld(Link is external), the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion(Link is external)

Judith Weisenfeld

Tell us about a particular book on your shelf.

I have a well-worn copy of Octavia E. Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” on my shelf that was the final book I read with students this past spring semester in my undergraduate seminar on “Race and Religion in America.” Butler’s 1993 novel is set in America in the 2020s in the context of environmental degradation, disease, the destructive social consequences of corporate greed and wealth inequality, rising nationalism and Christian fundamentalism, and government disinterest in meeting the basic needs of most residents. Lauren Oya Olamina, the main character, is a Black teenager who brings a religious message — “God is Change” — that offers the people around her different ways of thinking about the basis of community and the obligations we have to one another in times that generate heightened instincts for self-preservation as well as alternative imaginings of the human future and the future of human societies. I have included the book on the syllabus for this course for many years but found the discussion with students in the context of the pandemic to be especially rich as they entered into the world Butler presents to think more generally about race, religion, politics, community and possibility.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

My summer reading list is full of books that are related to my current research on race, psychiatry, and Black religions in the late 19th and early 20th century U.S., including several recent works on psychiatric hospitals and the experiences of Black and Native American patients — Martin Summers’ “Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation’s Capital” and Susan Burch’s “Committed: Remembering Native Kinship In and Beyond Institutions” top the list. I’m looking forward to reading Onaje X. O. Woodbine’s “Take Back What the Devil Stole: An African American Prophet’s Encounters in the Spirit World” to think about Black religious creativity and other ways of knowing in opposition to medicalization.

I’ve been listening to historian Kidada Williams’ podcast “Seizing Freedom(Link is external)” and am eager to finish the first season. It has a compelling combination of narrative episodes that show how Black people forged lives and communities in the wake of slavery; interviews with scholars, including Princeton’s own Tera Hunter(Link is external) (Link opens in new window); insight about researching and writing histories of Black freedom; and character spotlights that highlight the stories and voices of people who made freedom.

I have several recent books on Black women’s political activism on my list: Martha S. Jones’ “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All” and Alison M. Parker’s “Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell.” And, I’m very excited to read Olivette Otele’s “African Europeans: An Untold Story” and Yaa Gyasi’s novel “Transcendent Kingdom.”

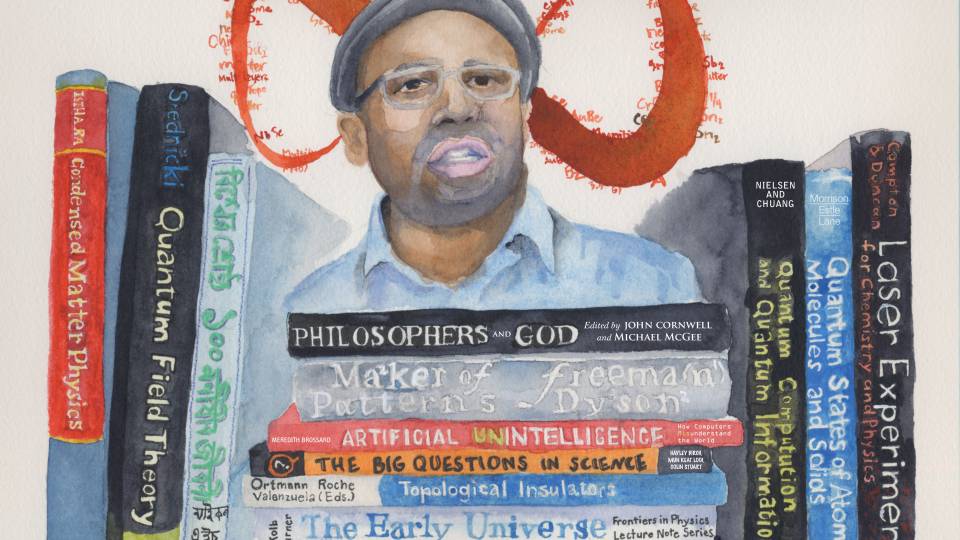

Frederick Fitzgerald Wherry(Link is external), the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917 Professor of Sociology(Link is external)

Frederick Fitzgerald Wherry

Tell us about the books on your shelf.

Because I am energized by work on economy and society, I tend to look for stories that demonstrate how our interpersonal relationships and our institutional rules shape our responses to debt. Why do we think that some debtors are deserving of dignity, or even a fresh start, but others are not? These books are informing the work of my newly launched Debt Collection Lab(Link is external).

These questions have taken me to the nation’s second founding, just after the Civil War. When we “began again” — to borrow from Eddie Glaude Jr.(Link is external) (Link opens in new window)‘s recent book “Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own” (that was last summer’s reading) — what did we do with people’s unpayable debts and why? Helping me in this exploration is Elizabeth Lee Thompson’s “The Reconstruction of Southern Debtors: Bankruptcy after the Civil War,” where she details how debt forgiveness seemed to make sense just after the Civil War, at least when it benefited those deemed to be deserving of life’s good things. I’m bringing this study in legal history together with W.E.B. DuBois’ “Black Reconstruction in America” and Eric Foner’s “The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Made the Constitution.” I’ll be zipping into these well-known works with deliberate care so that my readings of newspaper articles from that time period can be made sense of. I’m also reading “The Sympathetic Consumer: Moral Critique in Capitalist Culture” by Tad Skotnicki to think about how social movements over the last three centuries have generated, or failed to generate, regard for the victims of capitalism.

What’s on your summer reading/listening list?

As I think about my summer readings, I’m reminded that there really is no frigate like a book (to borrow from Emily Dickinson). It is a real joy to set sail.

I keep “Notes of a Native Son” and other things Baldwin by my bedside, along with The New Yorker and The Book of Common Prayer. (I’m a lay Eucharistic minister in the Episcopal church.) Before night falls, though, my audible books accompany me and my dog Hamel as we make our way through town. This summer, my list includes some old and some new:

- “The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America” by Greg Gandin

- “Real Life” by Brandon Taylor

- “Dubliners” by James Joyce

- “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together” by Heather McGhee

- “The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans — and How We Can Fix It” by Dorothy A. Brown

- “O, Pioneers” by Willa Cather