Princeton University President Christopher L. Eisgruber speaks with Irina Aranovich, general supervisor of Princeton's Diagnostic Laboratory, on a tour of the campus’ new COVID-19 testing facility in October 2020. The testing lab is an integral part of the University’s overall health and safety measures during the coronavirus pandemic.

Princeton University President Christopher L. Eisgruber sent his annual State of the University letter to faculty, students and staff on Thursday, Feb. 4, reflecting on the role of the University in a time of crisis.

Eisgruber wrote: “In a more ordinary year, I might use this letter to describe plans for the coming semester. In this exceptional year, when my colleagues and I have already written to all of you many times about the crises that confront us, I want to speak to more fundamental issues, issues about what it means to be a great research university at a time when the political controversies of the moment press upon us with searing moral urgency.”

To provide opportunities for community discussion of the topics in the letter, Eisgruber will discuss the letter and invite questions at two open meetings this month.

• All students, faculty and members of the broader University community are invited to join the upcoming annual Town Hall meeting of the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC). The CPUC virtual meeting will take place 4:30 to 6 p.m. on Monday, Feb. 8. In the question and answer period for this meeting, priority will be given to council members and to student questioners. Attendees can register online.

• A second Town Hall virtual webinar for University staff members will be held 11 a.m. to noon on Wednesday, Feb. 24. Registration is available online, and all employees are welcome to attend. The University will provide employees with paid release time so they can attend this meeting during normal work hours, subject to supervisory approval in order to maintain normal operations.

The State of the University letter is available as a pdf and is printed in its entirety below.

The University’s Role in a Time of Crisis

State of the University Letter, February 2021

Christopher L. Eisgruber

In the twelve months since my last annual letter to the Princeton community, our nation and our world have experienced a series of crises that made this year among the most challenging and difficult in the University’s history.

In March a worldwide pandemic forced us to send undergraduate students home, severely restrict campus operations, and move teaching online. Almost a year later, COVID-19 continues to sicken and kill people around the globe. Many Princeton families have lost loved ones to the disease, and all of our lives have been disrupted.

Last summer, an overdue national reckoning with racism, prompted by deeply disturbing incidents of police violence against Black people, demanded that we once again press ourselves to achieve racial equity more fully at Princeton and beyond.

Most recently, a sitting American president refused to acknowledge his electoral defeat and stoked a mob that invaded America’s Capitol.

In a more ordinary year, I might use this letter to describe plans for the coming semester. In this exceptional year, when my colleagues and I have already written to all of you many times about the crises that confront us, I want to speak to more fundamental issues, issues about what it means to be a great research university at a time when the political controversies of the moment press upon us with searing moral urgency.

Annabel Lemma, a graduate student in chemical and biological engineering, conducts research in the Brynildsen Lab. Health protocols, including mask wearing, are being enforced to keep faculty, students and staff safe from the coronavirus while working indoors.

Glimmers of Light after a Year of Crisis

We begin the new semester with reasons for optimism and hope. We have learned to mitigate the pandemic through the use of masks, social distancing, handwashing, and regular testing. Scientists have developed vaccines in record time.

At Princeton, students, faculty, and staff have risen to the challenge in a multitude of ways. Information technology has permitted us to sustain many activities, including this University’s educational mission, in ways that would have been unimaginable even a decade ago.

As a result of extraordinary work by a vast number of people, we were able to offer all of our undergraduates and graduate students the opportunity to return to campus for the spring term, while also sustaining remote options for those who wanted or needed them. Though many cherished activities remain in hiatus, we are working together with our students on campus and around the world so that they can continue forward toward their degrees.

Because infection rates remain high throughout the United States, the semester ahead will be another difficult one. Life on campus will be decidedly different from normal, but if we are vigilant and careful we should be able to handle the challenges ahead.

Much remains uncertain, but, as the vaccine rollout continues, we are planning for the fall with the expectation and intention of resuming fully in-person residential instruction. We will have to monitor and heed public health guidance as we decide when other campus activities—conferences, lectures, and the full panoply of intellectual colloquy—can resume.

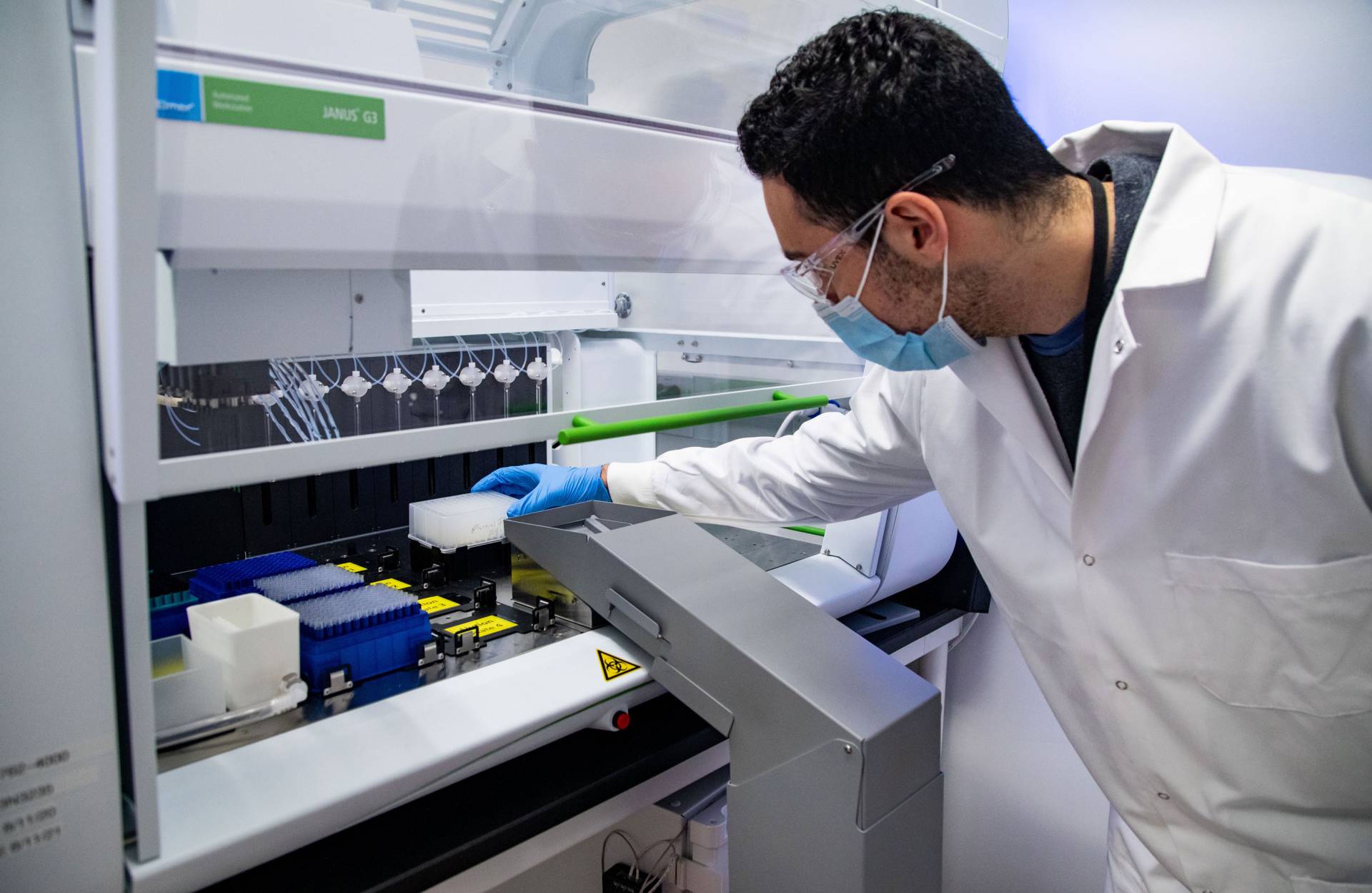

Princeton’s COVID-19 testing laboratory facilitates increased testing capabilities with faster results — an important step as the University safely increases density on campus and supports the return of residential education. Princeton is one of only a few universities in the country without a medical or veterinary school to build a federally certified COVID-19 testing lab. Pictured: Joshua Jacobson, a lab technician.

The University’s financial condition is significantly stronger than we anticipated last March. On campus, our loyal alumni have helped the University meet new costs for online instruction and our campus testing laboratory. Markets, which dropped last spring, have risen sharply.

Our national reckoning with racism has been intense and wrenching, but it also presents an opportunity to pursue a better future. On our campus, I have seen people demonstrate a new desire to understand what systemic racism has meant in America, and fresh commitment and energy in the pursuit of racial equity and inclusivity.

We need to sustain that engagement for years to come. There is no vaccine or injection that can produce a just and equitable society; the quest requires unflagging dedication.

And if it felt as though our democracy and our Constitution were dangling by a thread on January 6, the thread held. Congress certified the results of the election. President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., took office on January 20. Recognizing the need to heal a divided nation, the new president called upon Americans to “see each other not as adversaries but as neighbors” and to “treat each other with dignity and respect.”

Life on Princeton’s campus is decidedly different as students return for the spring 2021 semester. Upon check-in at Jadwin Gymnasium, they received COVID-19 testing kits, among other supplies, to support a safe residential environment.

The Importance of Institutional Values

An inaugural address can lay out new directions, but it cannot cure the plague of partisanship and mistrust. America’s divisions run deep. They affect how people view our country, and they also affect how people view America’s colleges and universities.

I see these divisions daily in the mail that I receive, electronically and on paper. Some people insist that the University should take bold positions on policy issues they deem essential to the world’s future. Others insist that the University should be fastidiously “neutral,” taking no positions on anything.

Surprisingly often, people ask me to “denounce” or “condemn” someone or something—a politician, an alumnus, a student group, a faculty member, an outside speaker, or a corporation—with whom they disagree. Toward the end of her term as Harvard’s president, my friend Drew Faust observed that some people seemed to want her to be the university’s “denouncer-in-chief.” She rightly said that was not the president’s job.[1]

Princeton’s 17th President William G. Bowen (pictured in 2008) was an advocate of “institutional restraint” when considering the expression of ideas and called the “open-minded search for truth” the University’s highest value.

As you might imagine, I have strongly held opinions on nearly all the political topics about which people write to me (though I do not share the zeal for denunciation manifested by some of my correspondents—there are better ways, in my view, to talk about politics and values). Earlier in my career, as a professor whose teaching and research focused on the Constitution, I published arguments about a wide variety of sensitive and controversial topics. I thought it my responsibility to do so, and I relished the opportunity.

My responsibilities as president are different. My job is not to declare my own opinions but rather to protect the ability of others to do so as part of the vigorous, truth-seeking teaching and research that is the core of this University’s mission.

As William G. Bowen, Princeton’s 17th president, put it, “The University as an institution must exercise a significant degree of institutional restraint if its individual members are to enjoy the maximum degree of freedom.”[2] He continued, “The absence of an institutional statement of ‘orthodoxy’ lessens the risk that faculty or students will be favored in some way—or will think that they may be favored—by taking the ‘right’ position on a controversial question.”[3]

Some people characterize, and often criticize, this institutional restraint as “value neutrality.” President Bowen disagreed with that description, as do I. He said,

[Princeton] is a value-laden institution, and it is for that reason that I avoid using the word ‘neutrality’ to describe its aims …. But the University’s core values emanate from its character as a university. In this setting, open-minded search for truth is itself the highest value; it is not to be sacrificed to anything else.[4]

Princeton and other universities depend on a commitment to institutional values—a commitment, for example, to protecting open and honest truth-seeking argument even when it leads in directions that we find uncomfortable, or when it includes the expression of views that we find offensive.

Institutional values are inherently demanding and fragile. They require us to bracket our personal convictions—not just our interests, mind you, but thoughtful and value-laden judgments about important issues—to protect processes that allow us to work together in the longer term. These values presuppose a faith both in those processes and also in one another.

Electoral democracy, and in particular the idea that electoral losers should willingly yield to victors, is perhaps the most basic illustration of an institutional value—and until recently, a principle that we took for granted in this country. People sometimes explain this value as a matter of taking turns: the losing party should acknowledge defeat today so that it can expect the same when it prevails.

Princeton and other universities depend on a commitment to institutional values, President Eisgruber wrote in his annual letter. Pictured: the University’s informal motto, “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity” carved into a stone medallion at the intersection of walkways in front of Nassau Hall.

Such partisan, self-interested calculations can provide only a flimsy foundation for electoral democracy. That is why I think that President Biden was correct when he asserted, adapting an idea from St. Augustine, that “a people [is] a multitude defined by the common objects of their love.” Our political institutions rest ultimately on a shared faith that, despite all our differences and divisions, we are one people, so that our future depends on the ability to move forward together.

Universities, too, require a community of people unified by the shared objects of their love: values such as learning, truth-seeking, mutual respect, creativity and innovation, honesty and service; the rites and rituals that mark the transformative passages of collegiate life; and friendships and associations nourished by a common mission.

Princeton is a university that attracts especially intense devotion from its community. We benefit not only from shared commitments to the University’s scholarly values, but from the affection that students, faculty, staff, and alumni feel for the particulars of their experience on a campus where, as Toni Morrison said in her wise and lyrical essay, “The Place of the Idea; The Idea of the Place,” “Every doorway, every tree and turn is haunted by peals of laughter, murmurs of loyalty and love, tears of pleasure and sorrow and triumph.”[5]

Free Speech and Truth-Seeking

Crises inevitably endanger and stress these precious institutional values. They test our commitment to long-term principles and practices against urgent imperatives of the moment. They also raise questions about how to apply those principles and practices to changed and charged circumstances.

These stresses are manifest in the heated debates about free speech on college campuses. I am a passionate defender of free speech. Vigorous argument is essential to truth-seeking and scholarship. On college campuses in particular, we should meet falsehoods and offensive arguments with better speech, not with censorship, suppression, or punishment.

Free speech and truth-seeking require not only the absence of formal restraint or disruption, but also a willingness to learn from those with whom we disagree. We impoverish our discourse and ourselves if we are quick to ostracize speakers who say things that offend us.

Our University’s core value, however, is truth-seeking, not free speech per se. They are not the same thing. The reckless expression of offensive or false ideas may be protected speech, but it is utterly inconsistent with scholarly ideals. It corrodes, rather than serves, the cause of truth-seeking.

Universities accordingly regulate the expression of ideas in many ways. For example, we give students grades and make tenure decisions on the basis of scholarly norms designed to distinguish better arguments from worse ones. We encourage and counsel members of our community to treat one another civilly and with respect. We honor students, and recommend them to others, on the basis of judgments about their values and character as well as their intellectual achievements.

People sometimes suppose that if a university genuinely supports free speech, it must be equally welcoming of speakers from all positions or viewpoints, or at least all politically popular positions and viewpoints. That is not true.

To be sure, this University will fail in its scholarly and educational mission if we become an echo chamber in which viewpoints go unchallenged simply because they are popular amongst groups dominant on the campus. We will also fail, however, if we treat all opinions as equally legitimate, or if we neglect the importance of ensuring that talented people of all races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds can thrive as full participants in the truth-seeking discussions on our campus.

Our commitment to free speech may require us to treat even very offensive viewpoints as exempt from censorship or punishment, but it does not require us to treat all viewpoints as morally equivalent. We can and should regard some positions as dishonest or shameful.

One of the lowest points of Donald Trump’s presidency, for example, was his disgraceful statement that there were “very fine people on both sides” when white nationalists and Nazis marched on the University of Virginia’s campus.[6] Nothing in the ideal of free speech precludes us from passing judgment on morally odious or false beliefs. Free speech affects how we pass such judgments, not whether we can do so—indeed, it is designed to facilitate (among other things) judgments about truth and morality.

When prominent government officials recklessly and persistently disregard moral, scientific, legal, or historical truths—by lying about elections or public health measures, for example—the institutional responsibilities of a university acquire added dimensions. Universities must still avoid institutional orthodoxies. They must also, however, emphasize the enduring importance of the distinction between truth and falsehood, and they must steadfastly resist any suggestion that they owe equal respect to opinions that are false, regardless of how popular those views may be.

Lessons from Robert Goheen’s Presidency

Robert F. Goheen, Princeton's 16th president

The tensions universities face today are acute but far from unprecedented. Princeton and other universities wrestled in the past with how to treat white supremacist speakers on their campuses, and we can learn from our predecessors.

Professor Eddie R. Cole’s excellent book, The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom, contains a fascinating chapter on Princeton President Robert F. Goheen, whose decency and values I admire greatly. Cole notes that Goheen had earned a national reputation as an advocate for free speech on campus who “believed that hearing a variety of voices—conservative, liberal, and moderate—was key to a strong institution.”[7]

His book examines at length Goheen’s response when Princeton students in the Whig‑Cliosophic Society invited Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, an outspoken segregationist and racist, to speak at Princeton in the fall of 1963. Goheen publicly condemned the invitation, saying that it ran “hard against a basic tenet of the University,” namely, the “fair and equal treatment of all persons.” Goheen said that the invitation was “untimely and ill‑considered.”

Goheen nevertheless reaffirmed the University’s commitment to “free inquiry and debate,” a commitment which protected students’ right to hear even views he regarded as distasteful. Goheen’s administration worked successfully both to permit Barnett’s address—which took place before a capacity crowd in Alexander Hall—to proceed uninterrupted, and to facilitate peaceful protests by civil rights groups.

According to Cole, a number of people criticized Goheen in the name of “free speech” because he publicly disapproved of Whig-Clio’s invitation to Barnett. In a letter to an angry alumnus, Goheen explained why he thought Barnett should not have been invited. Goheen’s reasoning made clear that Barnett was not simply someone who had propounded an offensive doctrine or said something that was (in today’s parlance) “politically incorrect.”

“The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom” by Eddie R. Cole (Princeton University Press, 2020) draws upon the example of former Princeton President Goheen, who earned a national reputation as an advocate for free speech on campus.

Goheen said that he reacted strongly to Barnett because he was a public official who had behaved unconscionably through “his open defiance of the laws of the United States, his actions so purely conducive to public violence, and his interference, as a governor, in the affairs of a university.”[8] Goheen also believed that Barnett’s presence on the Princeton campus was especially damaging because this University’s research and teaching excellence would ultimately depend on integrating and diversifying its student body and faculty.

According to Cole, Goheen was frustrated because “people were more upset over Goheen’s assertion that the Barnett invitation was a bad idea than racism itself.”[9] Goheen’s frustration prompted him to act: in the wake of Barnett’s speech, Goheen rededicated himself to racial justice.

At a board meeting on October 25, 1963, Goheen “told [Princeton’s] trustees … that the president’s office would focus on equality for Black people as long as he led the University.”[10] Cole suggests that the controversy over Barnett’s speech “mobilized Goheen, and for the rest of the 1963-64 academic year, Princeton launched its first campaign in university history to address racial inequality.”[11]

Bob Goheen’s unstinting commitments to both free speech and racial justice provide models for our own day. We must let speakers have their say, but that does not mean that all views or all speakers are equally deserving of our respect.

In general, the University should leave it to its individual members—its faculty, students, staff, and alumni—to debate which views are right or wrong, respectable or not. In some cases, however, my colleagues and I in the University administration will need to speak up for what Goheen called its “basic tenets,” including its commitments to racial equity and inclusivity.

Fighting for Racial Equity

Princeton’s efforts to achieve racial equality, which President Goheen began in 1963, continue today. I expect he would be both proud of the progress that Princeton has made and insistent that we must always push ourselves to be better.

Last summer, as America and the world reckoned again with the harm wrought by racism, we dedicated ourselves to new efforts to achieve inclusivity and fight systemic racism, a term that refers to racial inequities perpetuated through stereotype or the operation of apparently neutral systems. We continue to pursue those efforts; you can find information and updates about them on our racial equity webpage.

Some people have asked me how systemic racism could possibly affect people at Princeton after all that we have accomplished since Bob Goheen announced his commitments to racial justice in 1963. The question is a reasonable one. Princeton’s campus is far more diverse and inclusive than most American institutions. Nearly all Princetonians take pride in that diversity. Though they may disagree about the means to achieving racial equity, they embrace the goal.

The nation’s reckoning with racism after the death of George Floyd in May 2020 drew protests against police brutality and racial injustice, as well as a renewal of Princeton’s commitment to the pursuit of racial equity and inclusivity.

Yet, despite these accomplishments and good intentions, students who are members of underrepresented minority groups still report on average that they feel less welcome than other students on most college campuses around the country, including this one. One can understand why that is so. It is not uncommon, for example, for Black or Latinx students to hear someone say that they received a place at Princeton only because of their race—a statement that is always flatly false, because nobody gets admitted to this University without demonstrating exceptional talent and achievement.

We know that comments of this kind cut especially deeply because of the many other inequities—in policing, in health care, and in employment markets, for example—that Black and brown people face in American society. And we know, too, that these disadvantages, and the stigma and stereotypes accompanying them, adversely affect the ability of students from underrepresented groups to realize their full potential at America’s colleges and universities, including Princeton.[12]

Taking on systemic racism means attacking these inequities, inequities that may persist even in a community that recognizes racial equality, mutual respect, and inclusivity among what Bob Goheen called its “basic tenets.”

As most of you know, last September the Trump administration’s Department of Education announced an investigation of Princeton because we declared our intention to address the effects of systemic racism on our campus and beyond. The Trump administration’s specious theory was that any institution that recognized the impact of systemic racism thereby confessed to having violated federal anti-discrimination laws.

That was, as I expect even the Trump administration’s lawyers knew, pure baloney. Princeton University is in full compliance with all anti-discrimination laws. We take pride in our University’s energetic commitment to equality and inclusivity. Our initiatives to fight systemic racism are part and parcel of that commitment—an effort to go above and beyond what the law requires, as all of us must do if we are to realize our aspirations at this University and in this country.

Legislators, other colleges and universities, and a multitude of professional organizations came quickly and emphatically to Princeton’s defense. We are grateful for their stalwart support. After its initial letter to us, the Department of Education took no substantial action on its bogus “investigation” except to close it as the Trump administration left office.

President Goheen, top left, speaks on the steps of Nassau Hall during a May 1968 protest that drew students, faculty and staff, as well as the national media. Goheen, a campus free speech advocate committed to racial justice, led the University through numerous protests during his tenure from 1957 to 1972.

Moving Forward Together

The crises facing us today will pass, but the questions they have raised will demand our attention for years to come. We will press onward with the actions and conversations required to make this University stronger, more inclusive and equitable, and truer to the aspirations that we cherish.

Doing so will require more discussions about challenging topics including race in America and at Princeton. I recognize that those conversations, while necessary and valuable, can also be painful and subject to misunderstandings.

It is easy to wish we were in quieter, less demanding times. On some days, that’s exactly how I feel. But I also know that Princeton is at its best when we wrestle with the questions that genuinely matter. That is the opportunity, and the responsibility, that we share in these turbulent days when multiple crises mark our lives.

I am confident that this special community of learning, with its shared love for our mission and for this place, can sustain the institutional values—of honesty, openness, mutual respect, and a devotion to learning—that this era’s difficult discussions demand.

I will close this letter by quoting once more from Bill Bowen, and in particular from his 1986 Commencement address, which focused on the University’s institutional values:

Institutions exist to allow us to band together in support of larger purposes; they permit a continuity otherwise impossible to achieve; and they allow a magnification of individual efforts. Learning to make the accommodations that institutional affiliation requires is not always easy, especially for the … ardent individualists we seek to educate here. But there is a need to cooperate and collaborate, as well as to strike out on one’s own, if important societal ends are to be served.[13]

He then addressed this appeal to the University’s newly minted graduates:

The University needs you. It needs your interest, your affectionate criticism, and your dedication. I think that you need it in turn, and at least as much, as an outlet for the best instincts within you.[14]

Certainly Princeton today needs all of you—students, faculty, staff, and alumni—as we venture forward in unprecedented and challenging conditions.

I am grateful for what all of you have done to help Princeton persist in its mission over the past year. I look forward to working with all of you as we ensure that Princeton emerges from this year stronger, more vibrant, and more fully inclusive than ever.

[1] “In the Age of Trump, Faust Treads Cautiously,” Harvard Crimson (February 14, 2017).

[2] William G. Bowen, “At a Slight Angle to the World,” reprinted in William G. Bowen Ever the Teacher 5, 9 (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1987).

[3] Id. at 10.

[4] Id. at 11.

[5] Toni Morrison, “The Place of the Idea; The Idea of the Place,” October 25, 1996, available at https://pr.princeton.edu/news/96/q4/1025spch.htm.

[6] Glenn Thrush and Maggie Haberman, “Trump Gives White Supremacists an Unequivocal Boost,” New York Times (August 15, 2017).

[7] At 240.

[8] Letter of Robert Goheen to C. W. Miles (October 8, 1963), quoted in Id. at 264.

[9] Id. at 258.

[10] Id. at 269.

[11] Id. at 265.

[12] Douglas S. Massey, Camille Z. Charles, Garvey F. Lundy, and Mary J. Fischer, The Source of the River: The Social Origins of Freshmen at America’s Selective Colleges and Universities (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2006).

[13] Ever the Teacher, 578-79.

[14] Id. at 579.