A cornucopia, a symbol of abundance, is filled to overflowing with fruit and vegetables.

Princeton’s vital research across the spectrum of environmental issues is today and will continue to be pivotal to solving some of humanity’s toughest problems. Our impact is built on a long, deep, broad legacy of personal commitment, intellectual leadership, perseverance and innovation. This article is part of a series to present the sweep of Princeton’s environmental excellence over the past half-century.

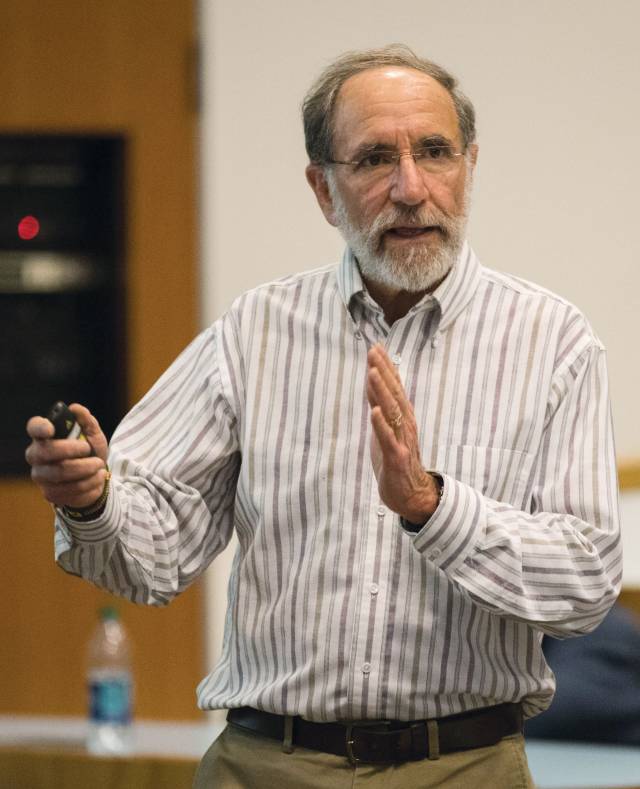

Timothy Searchinger

In 1995, Timothy Searchinger found himself in Washington, D.C., poring over the United States Farm Bill. An environmental lawyer and policy expert on wetlands restoration at the time, Searchinger discovered an obscure provision in the Farm Bill that would allow states to direct funding toward conservation efforts. While his efforts led to the restoration of approximately 2 million acres of land back into environmentally valuable riparian buffers and wetlands, his work on the Farm Bill led to another equally important personal discovery.

“Here was this huge swath of the middle of the country that’s practically all agricultural land, but hardly anyone from the national environmental community was studying the broader impact of agriculture at the time,” recalled Searchinger. This realization drove him to become one of just a handful of experts focusing on agriculture in relation to other pressing global environmental and socioeconomic issues. “Food is a critical and overlooked environmental issue that has a massive impact on planetary health,” said Searchinger. “It’s related to everything from climate change to biodiversity loss to questions of poverty and migration.”

Two decades later, now a research scholar at Princeton’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment, Searchinger’s work today combines ecology and economics to analyze the challenge of how to feed a world population that’s expected to grow by 2 billion people over the next 30 years, while reducing deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Searchinger was lead author of a series of five papers in the journals Science and Nature from 2008 to 2018 that recalculated the greenhouse gas emissions of biofuel and food production to include the cost of using land that could otherwise be storing more carbon in natural habitats.

Daniel Rubenstein

In 2019, he was lead author of a monumental report for the World Bank, United Nations and World Resources Institute that firmly establishes food and agriculture as a lynchpin global environment issue. The report provides a comprehensive, detailed “menu” of 22 specific solutions that should be deployed to meet rising food needs in socially equitable ways while avoiding further agricultural land conversion and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. “It would be difficult to overestimate the impact of Searchinger’s work in this field,” said Denise Mauzerall, professor of civil and environmental engineering and public and international affairs.

The report also captures the distinctive strength of Princeton’s growing group of researchers who focus on the topic. “We view food and agriculture as part of a larger environmental system where every part of the system affects all the others,” said Daniel Rubenstein, the Class of 1877 Professor of Zoology and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “How we use land for food production also affects greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, urban sustainability, human migration, and so many other areas. Food touches every part of human existence, providing a way of making people aware that how they eat can do much environmental good.” In addition to teaching the course “Agriculture, Human Diets and the Environment” at the Princeton Environmental Institute, Rubenstein’s own research on food has explored how humans and animals share landscapes and manage access to food.

“Princeton is unusual in focusing on food primarily from this broad, environmental perspective,” said Searchinger.

Few other universities are able to embed their food research in such a deep and interdisciplinary culture of excellence in the environmental field as Princeton has developed over the last half-century. Food studies may be the newest part of this long-standing environmental focus, but it’s part of a legacy that stretches back more than 50 years.

Food and biodiversity

One of Princeton’s environmental luminaries who attracted Searchinger to the University is David Wilcove, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute.

David Wilcove

In the mid-2000s, Wilcove viewed the explosive growth of palm oil plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia with alarm. Developers were clear-cutting tropical forests to grow palms that produced an oil commonly used as a cooking oil and in processed foods and beauty products and, increasingly, as a biofuel. The world’s insatiable appetite for this cheap oil eventually led to millions of acres of deforestation — releasing CO2 from forests while devastating regional biodiversity.

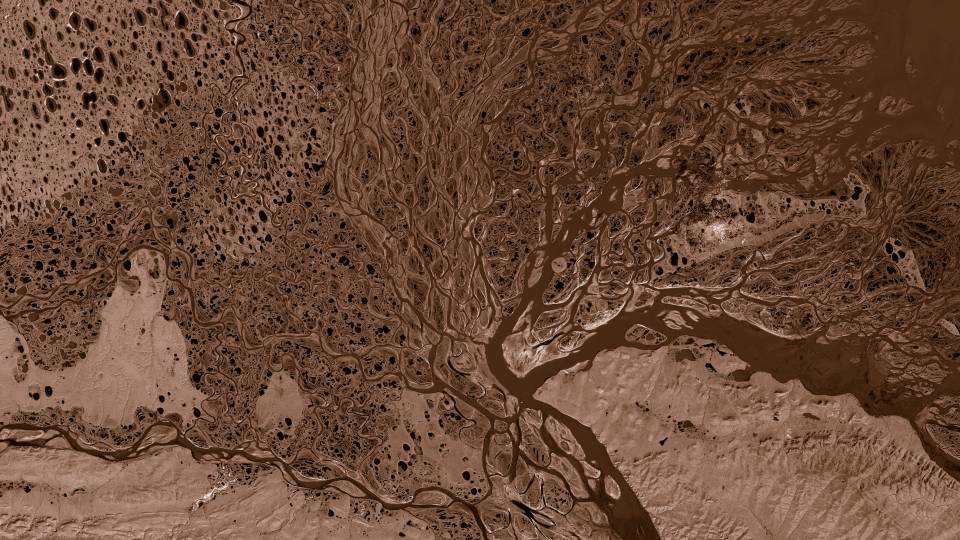

Wilcove and graduate student Lian Pin Koh were among the first to quantify the extent to which forests were being destroyed for oil palm production and the biodiversity costs associated with converting forests for agricultural purposes. Their research helped prioritize palm oil agriculture as one of the most pressing issues for tropical conservation efforts. Wilcove’s research group continues to study opportunities to work with farmers to support biodiversity across the globe, including some of his most recent work in the Western Amazonia of Peru.

“Land is a finite resource,” said Searchinger. “It needs to serve many growing purposes, including producing far more food for an increasing population, storing more carbon to address climate change and conserving the world’s diverse species. The only way we can do all three is more efficient use of land, meaning more food, more carbon and more biodiversity per acre.”

Food and greenhouse gas emissions

Denise Mauzerall

Other major groups on campus have taken different approaches to studying food. As Searchinger points out, agricultural activities account for about one-quarter of current global greenhouse gas emissions, creating cause for concern in light of growing populations.

“We must find ways to produce more food without expanding agricultural land or using significantly more nitrogen fertilizer in order to both protect biodiversity and reduce air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions,” said Denise Mauzerall, whose work as an atmospheric scientist and policy expert spans energy, agriculture, air pollution and human health. Mauzerall’s group has studied the air quality and climate benefits of increasing the efficiency of nitrogen fertilizer use so that yields are maintained while emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases are reduced. Her group is also studying the potential benefits of shifting diets to include less beef and dairy products, the production of which lead to substantial emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

Meanwhile, through the Carbon Mitigation Initiative, interdisciplinary teams of Princeton faculty and researchers are working to develop more nuanced understandings of the mechanics of how plants, water and soils interact across a variety of landscapes. Their emerging research explores how agricultural practices and land management can be harnessed to optimize natural carbon storage in plants and soils, explained Jonathan Levine, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Amilcare Porporato, the Thomas J. Wu '94 Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

“There’s a lot of attention on cutting greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector, but way less attention to agricultural emissions,” said Searchinger. “If we don’t aggressively push innovations and link increased crop yields with forest protection, we’ll blow past our overall 2050 emissions targets.”

Food and migration

Michael Oppenheimer

But what happens when the rains slacken and food yields decline where they used to flourish? Increased migration from areas suffering climate impacts, according to Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute.

“Falling crop yields in certain places will have a big impact on where people live in the future, so it’s critical that governments start to plan for these shifts now,” Oppenheimer said. “At the same time some of the most vulnerable people may lack necessary financial resources and are compelled to remain in increasingly perilous circumstances.”

Oppenheimer’s group has studied the potential effects of climate variability on migration within countries and across international borders, including Mexico-US migration and internal migration within South Africa.

In the coming decades, many more people will be migrating to and living in cities. So what might these shifts portend for urban food systems and their environmental footprint?

Food and cities

Anu Ramaswami

With more than two-thirds of the world’s population expected to live in cities by 2050, urban sustainability will have an enormous impact on the global environment, especially food systems and land use.

“Food and infrastructure are so important — they’re the anchor sectors. Without them, we just can’t live in cities,” said Anu Ramaswami, the Sanjay Swami ’87 Professor of India Studies and professor of civil and environmental engineering, the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, and the Princeton Environmental Institute.

For more than 20 years, Ramaswami has been helping cities map their environmental footprint and develop strategies for climate action. Strategic interventions in urban food systems are critical to achieve environmentally sustainable, healthy, and more equitable cities, says Ramaswami. Her group’s recent research finds that dietary changes and improved food waste management would have the greatest benefits in shrinking cities’ food footprints.

“The way that cities access and consume food is a massive lever for global changes to food systems and their environmental impact,” said Dana Boyer, lead scientist of Urban Food Systems in the Princeton Sustainable Urban Infrastructure Systems Lab.

Cities are interested in improving the sustainability of their food systems, but they don’t always know what changes to make or where to start, says Boyer. Working with cities to gather information and understand their priorities, she and Ramaswami can then help develop concrete recommendations using the latest science and modeling. This approach harnesses both community participation and data-driven research to yield more sustainable outcomes.

Food systems are connected to so many other issues: human health, equity, culture, justice, the economy, and overall resilience, said Boyer. “Our work ties all of these factors together into a food action plan, with the goal of building more sustainable, healthier cities.”

Food resilience

There might have been very few people studying food from a global environmental perspective back when Searchinger began his research in this area, but in the last few years at Princeton, momentum has been building around the study of the food-energy-water nexus.

Recently the Princeton Environmental Institute established a multi-year Food and the Environment Initiative in collaboration with the Stockholm Resilience Center and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. This new initiative focuses on the resilience of food systems, including ecological, policy and human dimensions.

“The study of food shows us just how interconnected biological systems and human societies are,” said Simon Levin, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “Understanding what makes food and agricultural systems resilient will be critical for adapting to growing demand and increased environmental pressures,” he said.

With postdoctoral fellow Andrew Carlson, Levin and Rubenstein have recently studied the resilience of New Jersey dairy farms in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Across all of these areas, Princeton’s research on food continues to be defined by the central question: How do you feed the world without increasing emissions, fueling biodiversity loss and deforestation, or deepening inequality and poverty?

“Pursuing any one of these goals to the exclusion of the others will likely result in failure to achieve any of them,” said Searchinger.

Princeton’s cross-cutting and interdisciplinary approach to studying food will be key to finding the right solutions in the coming decades.