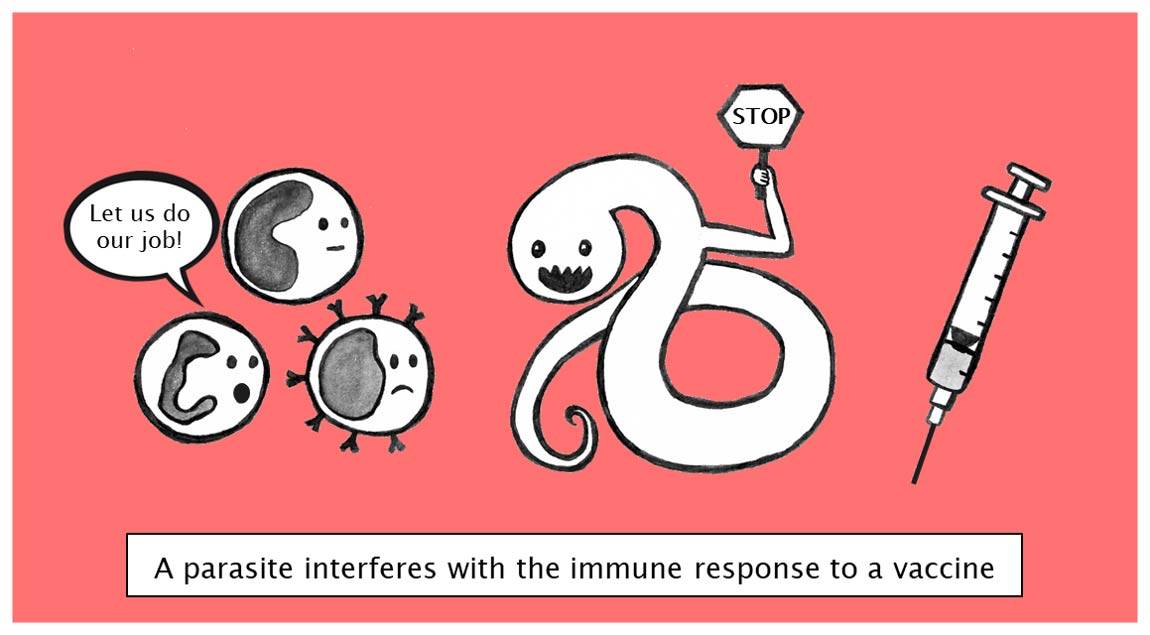

Vaccines are one of the most important tools we have in our defense against infectious diseases, but not everyone responds to vaccination in the same way. Parasites such as worms and viruses change the way a person or animal’s immune system functions, and this can affect their ability to respond to vaccines.

Since the 1960s, a steady stream of studies examined whether parasites might be interfering with immunization. Some have shown that they do, while others have been inconclusive. Our study, published in the July 31 issue of Vaccine, reviews the literature on parasite-vaccine interactions and quantitatively exposes patterns in these interactions.

Overall, we found that parasitic worms, protozoa and viruses do tend to interfere with immunization.

Parasites do tend to interfere with the immune system’s response to a vaccine, report a team of Princeton ecologists who reviewed and analyzed the literature of parasitic infections and vaccinations.

We found that the timing of infection relative to vaccination is important: For example, chronic worm infections were more likely to result in worse immunization outcomes than acute worm infections. The type of vaccine was also important: Vaccines that rely on T-cells were more likely to be blunted than vaccines that do not require T-cell involvement. Our results were consistent in a broad range of studies for various hosts and across various different types of vaccines. All of this points to the strength and importance of these interactions when considering the efficacy of mass vaccination schemes for a wide variety of infections, including influenza and COVID-19.

To discover all of this, we collated and analyzed studies that asked the question: Do parasites interfere with vaccination? We intentionally included both experimental and epidemiological studies, studies in both human and other mammalian hosts, and we defined parasite broadly to include helminths (worms), protozoa, viruses and bacteria.

Our findings are of importance to vaccine designers, medical practitioners and public health officials, because the potential presence of parasite infections needs to be taken into account when we are designing vaccines, administering vaccines to individual patients and implementing population-scale vaccination programs. Nearly a quarter of the world’s children are infected with parasitic worms such as roundworm and hookworm, so we expect that the efficacy of broadscale attempts to use vaccines to control common childhood infections such as measles, mumps and rubella will be reduced because of these worm infections.

Liana Wait is a graduate student in the Department of Ecology and Environmental Biology (EEB). She wrote this paper in collaboration with her advisers, EEB Professors Andrew Dobson and Andrea Graham. Graham is also the co-director of the Program in Global Health and Health Policy.

“Do parasite infections interfere with vaccination? A review and meta-analysis” by Liana F. Wait, Andrew P. Dobson, Andrea L. Graham, is available online and will be published the July 31 issue of Vaccine (Volume 38, Issue 35, 5582-5590). DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.064. The research was supported by Princeton University. The authors thank the Princeton Open Access Publication Fund Program for funding the open access publication of their article.