For her senior thesis, Audrey Shih, a chemical and biological engineering concentrator, investigated how specialized materials act to remove pollutants from the porous rock of groundwater aquifers. In this photo from summer 2019, Shih preps a small plastic apparatus containing material that simulates a porous rock environment. Graduate student Christopher Browne, behind, provides guidance. Shih’s 2019 summer research in Sujit Datta’s laboratory was supported by the summer internship program of the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

Audrey Shih entered Princeton with aspirations of using science to protect vulnerable people from allergens. “I have a severe peanut allergy, and I thought I might help come up with a method to detect allergens in food,” said Shih.

After declaring her concentration in chemical and biological engineering (CBE) and beginning her coursework in the department, “my interest shifted more toward materials science and the more physical than biological side of CBE,” she said.

An email to Sujit Datta, an assistant professor in the department, launched Shih on a two-year-long research project to help thwart a different type of chemical threat: pollutants like crude oil and mercury that can linger in groundwater even after major cleanup efforts. In Datta’s lab, she investigated how specialized materials act to remove recalcitrant pollutants.

Shih, a member of the Class of 2020, finished writing her senior thesis on the topic from her family’s home in Columbus, Ohio, after the University halted on-campus instruction and research activities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In recognition of her thesis work, Shih was one of two graduating seniors presented with the engineering school’s Lore von Jaskowsky Memorial Prize for Contributions to Research during Class Day celebrations on June 1. Shih, who completed a certificate in materials science and engineering in addition to her CBE concentration, also received an outstanding senior thesis award from the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials.

“It’s been harder to stay motivated and focused” at home, said Shih. “There were times when I wished that I could be in Firestone Library to work on my thesis.” She and a few friends tried using Zoom video conferencing to recreate the experience of writing at the same table — “just having each other on the call without really talking. But everyone’s in different time zones, so it was a little bit difficult,” she said.

Shih’s thesis focused on specially formulated chain-like molecules called polymers that can help flush contaminants from hard-to-reach crevices in underground aquifers. How these polymers move through porous rocks to dislodge pollutants — and why they are more effective in some settings than in others — is not well understood.

“Polymer solutions behave unlike most fluids. They have an elastic component to them in addition to being quite viscous, and when they go through porous spaces, weird things happen,” said Shih. “A lot of strain builds up as they’re trying to get through these little holes, and they form interesting flow structures.”

During the fall of her junior year, Shih began working with graduate student Christopher Browne to investigate the flow of polymers, using computational models and laboratory experiments to simulate the varied geometries and pore sizes of rocks in groundwater aquifers. In results published in March in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics, they found that under some conditions polymer solutions circulate in tiny eddies within the pores.

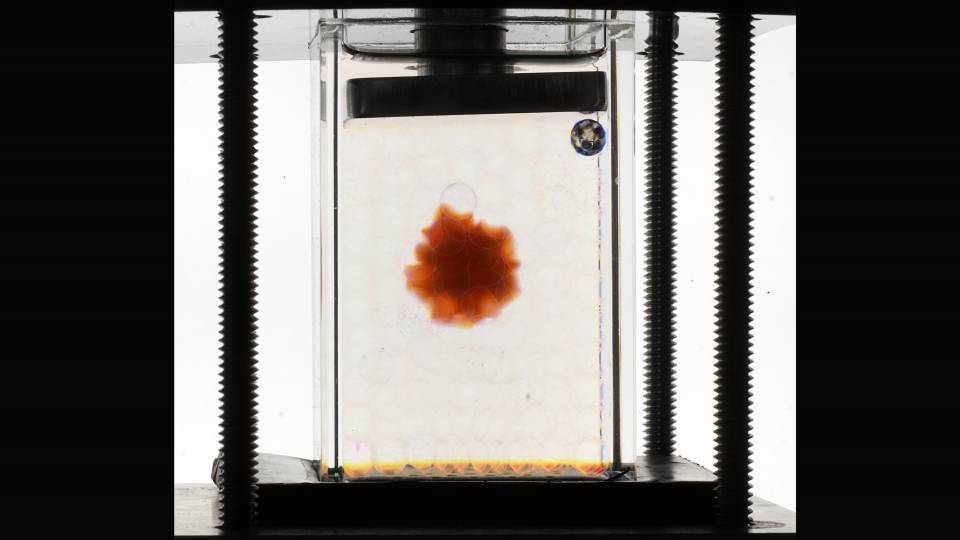

Shih built a device that allowed her to inject a stream of dye into the simulated rock along with the polymer solution — a way to determine how well a polymer might work in conjunction with another type of material to pick up pollutants. In this preliminary model of the device, clear polymer is entering from the right side of the device and moving toward the left. The photo behind the device shows the face of Squid, a dog owned by Datta lab graduate student Daniel Amchin.

Browne and Shih “were able to discover a new form of flow that polymer solutions manifest in porous media, and they were able to explain why it arises,” said Datta. “For her senior thesis, Audrey built on that work and took on a new, ambitious project to look at the implications of this unusual flow behavior when it comes to spreading things out in a porous rock. When Audrey first joined my lab we knew very little about how polymer solutions flow in porous media; now, these studies are part of an established thrust in my lab that we’re excited to push forward.”

Shih built a device that allowed her to inject a stream of dye into the simulated rock along with the polymer solution. The dye represents other substances, such as surfactants that help break up oil, which may be injected into groundwater systems along with polymer solutions to enhance cleanup efforts. Shih’s device offers a way to determine how well a polymer might work in conjunction with another type of material to pick up pollutants from pores in rocks.

Optimizing the new device took a good deal of trial and error, said Shih, as she worked to adapt the setup from previous experiments to enable the synchronous injection of a dye and a polymer.

“This setup at the inlet caused a lot of complications — a lot of leakages under these extremely high pressure drops that our experiments are associated with,” she said. “The setup ultimately did not work for me, so I started from scratch and created a whole new device.”

Shih was able to conduct a few experiments using the new device before returning home to Ohio in March. Although her results are preliminary, they suggest that “when you add polymers, the flow disperses better, so mixing is enhanced and your dye stream mixes with the bulk flow more quickly compared to a solution that has no polymer in it. This is good confirmation that polymer solutions can be used to enhance mixing” in groundwater cleanup settings, said Shih.

“I wrote a large part of my thesis about how I designed the device and modified it to make it work,” she said. “While my time for experimentation was cut short, I think this device will allow future students to continue the project.”

Shih will begin a Ph.D. program in chemical engineering at Stanford University this fall, with support from a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. Her thesis experience at Princeton helped solidify her decisions to pursue graduate study and to continue in the field of soft matter, which explores the properties and uses of polymers, foams, gels and other soft materials.

“Soft matter is really fascinating to me, and it has a lot of applications, including in biological systems like the human body,” said Shih. While she has pivoted from her earlier goal of helping those with allergies, Shih remains motivated to improve people’s quality of life through her research. “My work has focused more on environmental applications, and that also speaks to me,” she said.

Shih finished writing her senior thesis from her family’s home in Columbus, Ohio, after the University halted on-campus instruction and research activities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

While she had hoped to spend this summer traveling, Shih plans to make the most of her time at home by building her computer coding skills and playing the clarinet and piano. Besides her coursework and research, music played a major role in Shih’s time at Princeton. She said she feels fortunate that her professors and colleagues in the CBE department supported her musical endeavors and regularly attended her performances, encouraging her to continue playing music in the future.

Shih and four fellow members of the Princeton Pianists Ensemble spent about a month this spring producing a video of themselves playing an original arrangement by Shih, “Disney Fantasy Medley,” which they’ve called “the world’s first remotely performed piece for five pianos.” On May 23, Shih performed a virtual, livestreamed senior recital, with her mother and her sister filling in for Princeton students on collaborative pieces for violin, clarinet and piano.

“Audrey goes out of her way to take ownership of what she’s doing and push it along as much as she can,” said Datta. He noted that Shih used downtime during rehearsals of the Princeton University Orchestra (in which she played the clarinet) to address reviewers’ comments on the research paper she later published with Browne. “That level of dedication and passion is unique — it’s not something you can teach.”