In her latest book, “Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code,” Ruha Benjamin offers a detailed, critical and sobering view of the ways in which bias is infused into technology.

Since the book’s release in June 2019 by Polity Press, Benjamin, an associate professor of African American studies at Princeton, has captured a broad range of public interest in her analysis of how today’s technology — everything from phone apps to complex predictive algorithms — carries within it biases that can have a detrimental impact on certain communities or groups even when the goals for its use are lofty or altruistic.

Among the many examples she cites are:

• A gang database that is 87% black and Latinx with many names belonging to babies under the age of 1, some of whom were supposedly “self-described gang members.”

• A beauty contest judged by robots programmed through deep learning in which all the winners were white and only one finalist had visibly dark skin.

• A recidivism risk algorithm that wrongly predicted arrested individuals who would reoffend, with the formula more likely to flag black defendants and less likely to flag white defendants as future criminals.

• A Google Maps glitch that reads “Malcolm X Boulevard” as “Malcolm Ten Boulevard.”

“Race After Technology” presents a range of examples of discriminatory design and offers a toolkit for understanding the ways in which technology can reinforce and deepen societal inequities.

The book has found its way into the hands of business executives, medical professionals, high school students, tech creators and women’s advocates, among many others. The diversity of audiences discovering the book has been so extensive, that Benjamin decided to take inventory for herself a few months after its release.

“I was surprised at the variety of disciplines and practitioners that resonate with the problem of discriminatory design — many more than I thought,” Benjamin said. “So everything from nursing, business, professional schools, to different STEM programs to humanities.”

Through public lectures and virtual visits to classrooms and libraries, Benjamin has interacted with many of her readers while on sabbatical. (Many of these events occurred before the global spread of coronavirus that has curtailed public gatherings. Benjamin continues to meet with groups by videoconference and through online broadcasting, including reading "Stories from Around the World" for students in grades K-5 in partnership with Labyrinth Books in Princeton.)

More than 45 classes or programs used her book last fall, and she has presented to K-12 educators and administrators in several states. In recent months, Benjamin also has addressed the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, and international technology conferences in Kenya, Ethiopia, the Netherlands and England.

“Rather than have a quiet sabbatical where I hunker down and start a new project, I’ve been learning how people are engaging the work and how they’re applying it, and those conversations have been really fruitful,” she said. “And that’s what my hope was for the book, that it would be an instigator, provoking new kinds of conversations.”

An outgrowth of this is in rethinking and retooling the use of data for justice.

She recently announced a COVID-19 related project that tracks, synthesizes and situates data on the racial dimensions of the pandemic within historical and sociological frameworks. Benjamin received funding to hire a team of student researchers that will create a "Pandemic Portal" at the JUST DATA lab, which she founded at Princeton. The portal will shed light on how pre-existing social conditions such as poverty, racism and colonialism are determining COVID-19 outcomes.

Earlier this year, Benjamin made several appearances in the Princeton area, delivering a keynote talk at the Princeton Arts Council’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration and a lecture at the Princeton Plasma Physics’ Laboratory’s (PPPL) Science on Saturday program.

Andrew Zwicker, head of PPPL’s Office of Communications and Public Outreach and a New Jersey State Assembly representative for the 16th district, said Benjamin received an enthusiastic reception to her talk.

“Professor Benjamin’s research has shown that the root of the problem is much deeper than most people thought at first,” Zwicker said. “It’s much more subtle and much more critical. It’s not just these explicit biases.”

Zwicker has invited Benjamin to testify before the state assembly’s Committee for Science, Innovation and Technology, which he chairs. The committee recently held its first hearing on facial recognition and also is investigating the use and monetization of personal data.

“It is beholden upon us to continually be questioning how we are using automation and the impact it has on people,” Zwicker said.

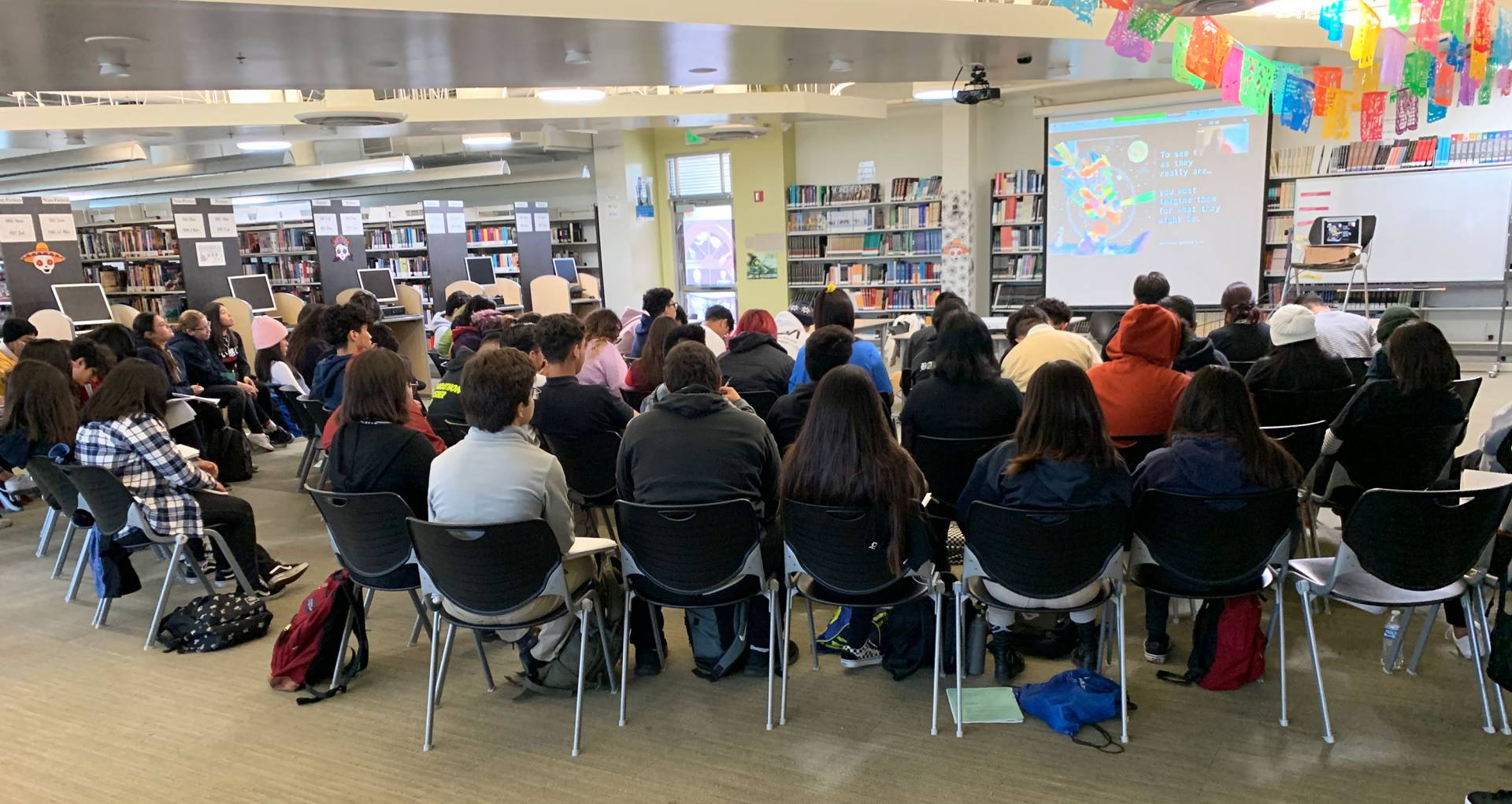

Kenneth Rodgers, curriculum coordinator for Synergy Quantum Academy High School in South Central Los Angeles, invited Benjamin to speak to seniors in his Advanced Placement Comparative Politics class. When the day arrived, about 100 students and staff members at the high school filled the school’s library to listen to her video call.

Many students at the school are interested in pursuing careers in engineering and computing, Rodgers said. “Her presentation and work that delves into all the implicit bias behind that gave them pause for something they had never considered before,” he said. “I think it added a certain gravitas to their career choices and the responsibility that may come with their future careers.”

Other students interested in the humanities learned lessons that could be applied to eventual careers in law and politics, and all took away some eye-opening truths about how bias in technology impacts their daily lives. “Whether it’s tracking movement or storing data or selling their data that might be collected on social media websites, they were very interested in that,” Rodgers said.

Benjamin has connected with her national and international readers in person and online. Shown: Students and staff at Synergy Quantum Academy High School in South Central Los Angeles fill the school’s library in October 2019 to join a videoconference with Benjamin to learn how her findings on technological bias might have impact on their daily lives.

Nourbese Flint, policy director and manager of reproductive justice programming for Black Women for Wellness in Los Angeles, first encountered Benjamin’s work when seeking experts who could provide insight into the future of reproductive justice. Benjamin has since spoken to the group several times.

“Thinking about how race, class, gender and the wide range of other -isms currently and in the future impact our work is vital to addressing the systemic and institutional oppressions that impact black women and girls,” Flint said. “Ruha’s work takes a critical look at how technology can be used as a tool to both widen oppression as well as alleviate historic barriers, and does so in a way that doesn't leave technology as a benign instrument that is only left to the whim of its user, but as an active thing that needs to be examined and explored.”

In this regard, Benjamin said “Race After Technology” is accomplishing what she had hoped.

“The book is not conclusive in the sense that this is not the only way to think about the relationship between innovation and inequity,” she said. “My aim is to raise questions, provide concepts, a toolkit and lens to think about a variety of technologies and fields.”

Benjamin will share many of these concepts in her Princeton class this coming fall titled “Black Mirror: Race, Technology and Justice.” The course uses the television show “Black Mirror,” which offers a speculative look at where technology is headed, as a jumping off point for discussion.

As part of the course, Benjamin said she will have students complete hands-on projects designing technology that does not reinforce the status quo or inequalities.

She also hopes to build on the book’s momentum to reach new audiences, specifically by collaborating with artists who can raise awareness in other ways. “There are other media we can use to creatively engage the ideas,” she said.

Benjamin said she will continue to speak with as many groups as are willing to listen. “I see this as an extension of my teaching outside the classroom, engaging with people, audiences, communities. It’s been really rewarding.”