Through close reading of texts spanning genres, students in the fall course “Literature and Environment” consider how storytelling illuminates environmental issues. Pictured: Julia Brazeau (left), a member of the Class of 2022, and Jenna Shaw and Alexander Gottdiener, both members of the Class of 2020, participate in a small-group discussion during a class session.

Students in several Princeton courses this fall examined the perils of climate change by considering how storytelling — with elements of description, language and structure — can influence people’s perceptions and fire up the imagination.

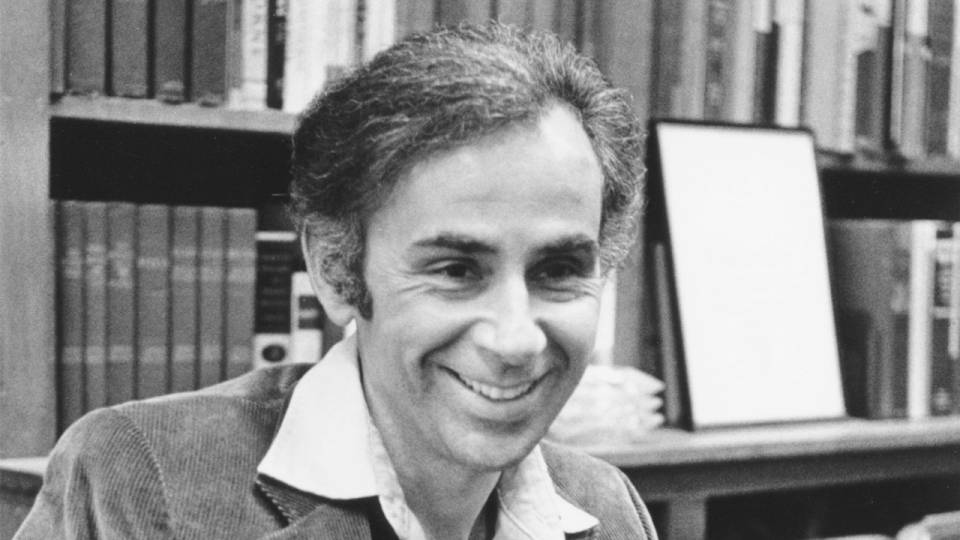

One of the classes in the humanities was “Literature and Environment,” co-taught by William Gleason(Link is external), the Hughes-Rogers Professor of English(Link is external) and American Studies(Link is external) and Kate Thorpe, a doctoral candidate in English. Read about another fall course focused on the environmental humanities, “Creative Ecologies: American Environmental Narrative, Media and Art (1980-2020).”

Paragraph, persuasion, perspective: Reading the environment

On a November afternoon, the 16 students in “Literature and Environment” settled into their seats in a Chancellor Green classroom. As backpacks flew open, a distinctive spot of color popped up around the table: Dr. Seuss’ 1970 children’s classic “The Lorax.”

Also on the docket: Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” (1962) — a rallying cry against the use of pesticides; and two depictions of a dystopic future evoked with unflinching immediacy, Elizabeth Kolbert’s “The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History” (2014) and “Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization (2015) by Roy Scranton, an Iraqi war veteran and 2016 Princeton graduate alumnus in English.

For those who haven’t picked up Dr. Seuss since being tucked into bed — or tucking a child into bed, a brief synopsis: The title character in “The Lorax” is a mustachioed little creature who tells a small child a dire tale about an idyllic, pristine ecosystem that collapses in a chain reaction when a tyrannical entrepreneur hacks down one thing — all the Truffala Trees — to make “thneeds,” a multi-purpose sweater.

Listing his points on a blackboard, Gleason invited the students to consider three strategies writers use to engage the reader to think about the environment: confronting uncertainty, initiating conversations and bringing the future closer.

Splitting the class into four small groups, one for each reading, Gleason and Thorpe floated among them, listening in for a moment here and offering a thought-starter question there. After about 10 minutes of lively conversation, the groups came together and compared notes.

Kicking off the discussion with “The Lorax,” Thorpe wanted to know: What classic literary elements does Dr. Seuss use to drive the story’s message home?

“The road in the middle of every page is a clear marker of the road we come from and the road we’re heading down,” one student said. “Metaphor, right!” Gleason pronounced, punctuating the air with a jab of chalk. “’Thneeds’ sounds remarkably like ’the needs,” said someone else. “Yes, language!” Gleason echoed. Another student jumped in: “The story starts with the present, then jumps to the past, so we have to figure out which direction we want to take; that becomes a value discussion, giving every child who reads this book the potential to effect change.” Nodding emphatically, Gleason said, “Absolutely, the temporal.”

With the other three readings, he and Thorpe had assigned the opening pages to compare how authors invite the reader into an imagined environment quickly. “You have 10 minutes or less to capture someone’s attention,” Gleason told them.

Kate Thorpe (left), a doctoral candidate in English, and William Gleason, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of English and American Studies, lead a class discussion. Their collaboration on the course is part of the Collaborative Teaching Initiative, which fosters graduate students’ professional experience through the design and co-teaching of an innovative undergraduate course.

Students expressed their fears about the effects of climate change.

Senior Audrey Davis first read Kolbert’s “The Sixth Extinction” in spring 2017 for the team-taught “Environmental Nexus” course, which was offered again this fall. While reading a passage that says: “… a hundred million years from now, all that we consider to be the great works of man — the sculptures and the libraries, the monuments and the museums, the cities and the factories — will be compressed into a layer of sediment not much thicker than a cigarette paper,” she said she couldn’t stop crying.

Davis, a concentrator in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs(Link is external) who is also pursuing a certificate in environmental studies(Link is external), said everyone in the “Literature and Environment” class was powerfully drawn to Scranton’s work. “It felt like: Finally, someone is not just telling us the truth, but giving us ways to adapt,” she said.

Class materials span centuries and genres, from Thoreau’s “Walden” and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” to the 2004 environmental disaster film “The Day After Tomorrow” and Suzannah Lessard’s 2019 essay collection “The Absent Hand: Reimagining Our American Landscape.”

Senior Bennett Weissenbach, a concentrator in English who is also pursuing a certificate in environmental studies, said: “I view the climate crisis as the greatest issue that our generation faces. Literature can help us think critically about our relationship to the natural world and thus mobilize action.” For his senior thesis, he spent two summers and part of last winter in Alaska, gathering material for a work of creative nonfiction about climate change.

The students’ final projects range from developing environmental class modules for schoolchildren to playwriting and other creative storytelling.

Senior Emma Hopkins, a concentrator in English who is also pursuing a certificate in urban studies(Link is external), is writing a fictional grant proposal for a playground that links literature and the environment. She said she drew inspiration from similar installations by Studio Ludo, a design firm she discovered while conducting research for her senior thesis on American playgrounds, and from the illustrative and linguistic style of “The Lorax.”

“Our students are deeply concerned with making a difference in the world,” Gleason said. “I hope they take away a new appreciation for how literature can prompt critical thinking, that literature isn’t just a thing to entertain us; it gives us access to some of our own most profound thoughts.”

Thorpe said: “As they go forward to try to make big and small changes in the environment, either individually, or maybe professionally, I hope that they have some tools from the humanities — how literature about nature has the potential to change how other people see and think about the world, that language itself matters as much as the subject that’s being communicated.”

Discovering how co-teaching creates a ‘richness’ in the classroom

The course is part of the Collaborative Teaching Initiative(Link is external), which fosters graduate students’ professional experience through the design and co-teaching of an innovative undergraduate course. Thorpe said the collaboration — from shaping the syllabus and carefully planning each 80-minute class session — has been rewarding for her, but also helped foster a “richness” in the classroom that contributed to the students’ experiences.

“I’ve learned so much from Bill’s experience teaching, and his care for communication and connecting to students,” she said. “Sharing the work of leading discussions and creative activities truly has allowed us to create a classroom of lively debate and enthusiasm for learning — and I am so grateful to our students for taking us up on this invitation to think through hard and pressing issues through our readings.”

“Kate’s excitement and energy in the classroom are amazing qualities,” Gleason said. “It energizes me every day to sit and talk with her about our course and what literature can do.”