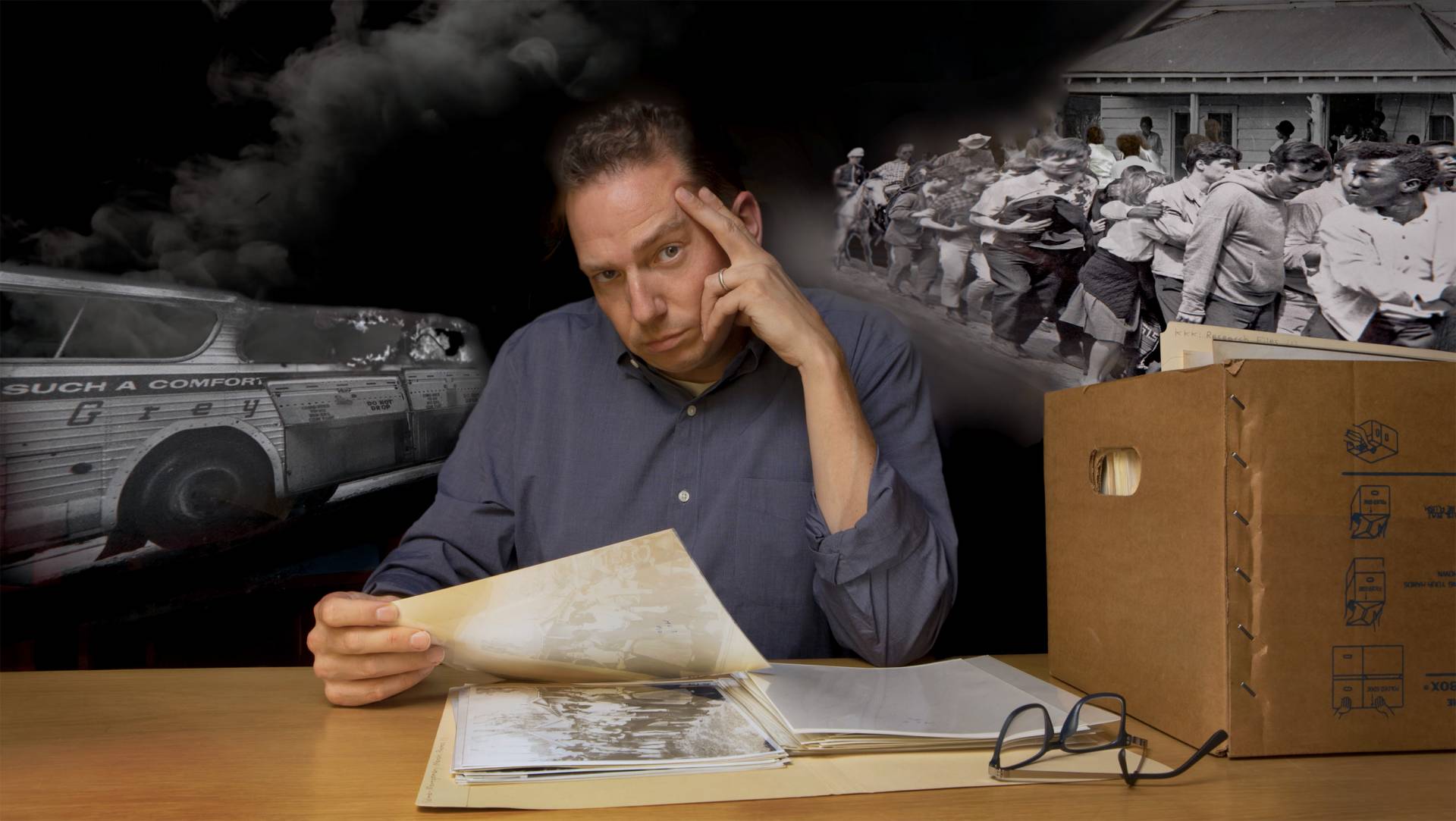

Historian Kevin Kruse is mining the newly opened John Doar Papers at Princeton’s Public Policy Papers for his next book, which will reconsider the civil rights era through the life and legacy of Princeton alumnus John Doar, an attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division from 1960 to 1967. Pictured here, Kruse examines Doar’s files documenting the attack on the Freedom Riders in Montgomery, Alabama, in May 1961.

Given his central role in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, John Doar should be a household name.

A graduate of Princeton’s Class of 1944 who served as an attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division from 1960 to 1967, Doar accompanied James Meredith to register for classes at the University of Mississippi, and he stared down Gov. George Wallace when Wallace took his famous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to prevent integration at the University of Alabama.

Doar worked alongside activist Medgar Evers to investigate voting restrictions against blacks in Mississippi, and when Evers was shot, Doar stood in the streets of Jackson at great personal peril to calm protests that brewed in the aftermath.

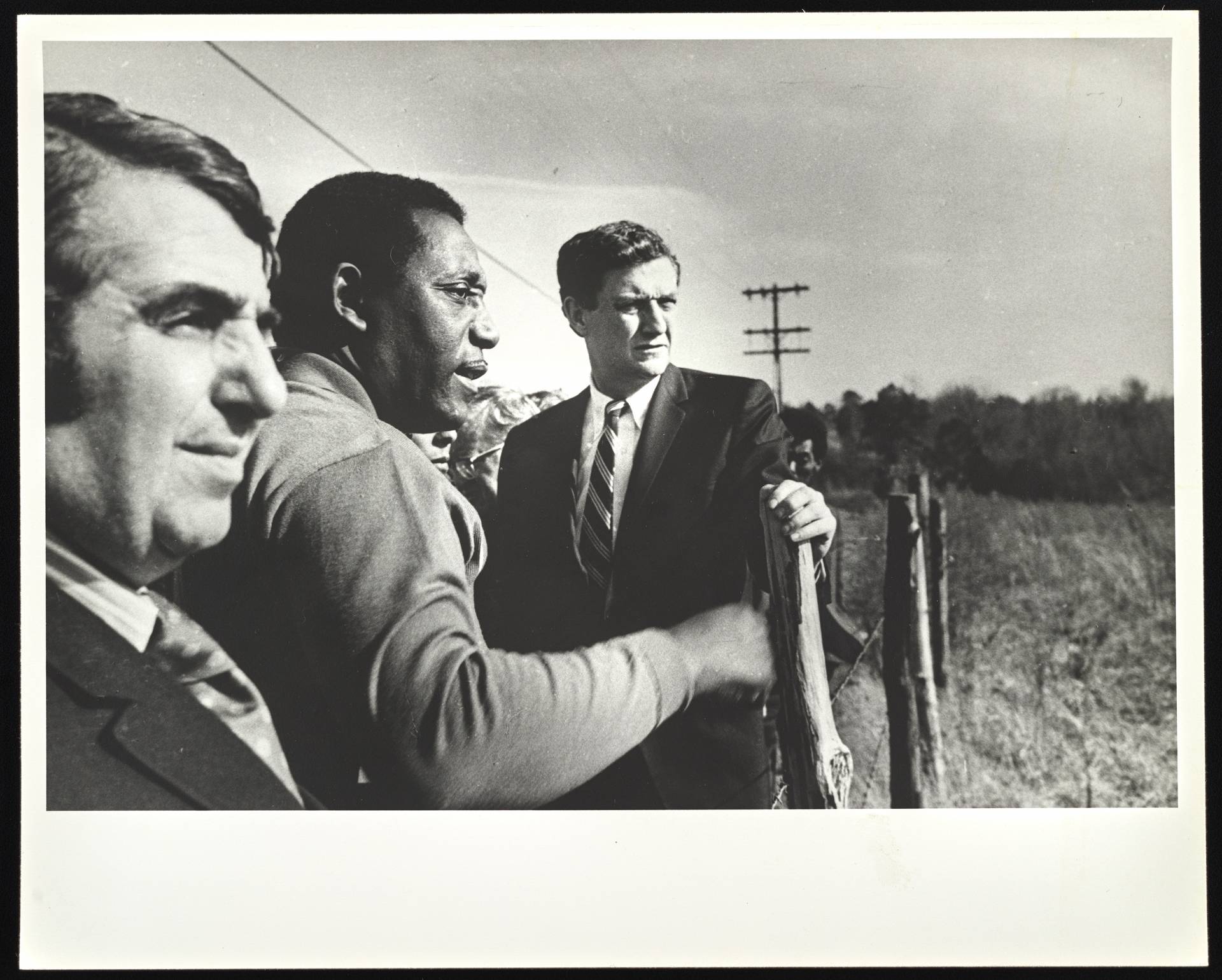

Doar, right, who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, stood at the forefront of the U.S. government’s work during the civil rights movement, both in court and out in the field. Here he is pictured during his investigation of the Freedom Riders attack. The civil rights activists were continuously threatened as they rode interstate buses to challenge the non-enforcement of court-mandated desegregation.

Doar was in Montgomery, Alabama, when the Freedom Riders were assaulted in 1961, then he walked ahead of the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965. He helped craft the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act and was key to their implementation across the South.

“When I explain him to friends who aren’t historians, I always describe him as this Forrest Gump or Zelig,” said Kevin Kruse, a professor of history at Princeton, referring to fictional characters who land themselves at the center of historical events. “He’s constantly in the background, but he’s actually, unlike those characters, there on purpose and having a real effect.”

Earlier this year, Kruse was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete what will be the first full assessment of Doar’s civil rights legacy. Kruse is writing a book on Doar’s storied career titled “The Division: John Doar, the Justice Department and the Civil Rights Movement.”

A scholar of 20th-century American history with a particular interest in segregation and the civil rights movement, Kruse is the author of “White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism,” “One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America,” and “Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974,” which he wrote with Julian Zelizer, the Malcolm Stevenson Forbes, Class of 1941 Professor of History and Public Affairs in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Doar, center, accompanies James Meredith, center right, as he attempts to enroll in classes at the University of Mississippi on Sept. 26, 1962, following a federal court order. Mississippi Lt. Gov. Paul Johnson, left, famously blocked Meredith’s entrance. Days later, a confrontation between segregationists and federal and state forces left two people dead and 300 injured.

The project was sparked by the donation of Doar’s papers to the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, a division of the Department of Special Collections at Princeton University Library, following Doar’s death in 2014.

The collection contains 265 large boxes (263.1 linear feet in total) filled with depositions, court records, investigation files, photographs, correspondence and notes, not only from Doar’s time with the Justice Department, but also from his work as president of the New York City Board of Education (1968-69), his tenure as president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Development and Services Corporation in New York City (1967-73), and his appointment as chief counsel of the House Judiciary Committee during the Watergate hearings (1973-74).

“I’m excited that we have it, I’m glad that we have it, and even though John Doar is not a household name, I know it’s one of the most important collections I’ve brought in,” said Dan Linke, University archivist and curator of Public Policy Papers. “It was a remarkable life and thankfully well documented.”

Doar kept his papers on deposit at Mudd Library in the 1970s and 1980s — a service no longer offered — using them for his own research and writing.

Linke, who met Doar soon after becoming head of Mudd Library in 2002, spoke with Doar several times over the years about his intentions for the papers. Doar wanted the materials to be closed for a certain period to allow an official biographer to review them first. He signed a deed of gift before he died, which his family gave to Mudd Library in 2015, Linke said.

Linke remembers Doar, a former University trustee and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, as a modest man.

“He had no sense of airs about himself, but he was very proud of the work he had done — that was very clear,” Linke said. “He also had a wry sense of humor.”

When the library completed the acquisition of the collection, Linke reached out to Kruse to write a quote about the historical significance of the papers for a press release.

“I tried to write a single sentence, but it took me three paragraphs to say what I wanted to say,” Kruse recalled. “And as I did, I thought, ‘Wow, this is going to be a great book for somebody.’ And then I took a beat, and said, ‘I want this to be my great book.’”

When Linke later asked Kruse if he could recommend a historian to be Doar’s biographer, Kruse volunteered himself. The Doar family met Kruse and granted him exclusive access to the collection for two years. Kruse began his research in summer 2018 and is continuing to review the files through the 2019-20 academic year.

“Normally collection boxes are thin ones, but these are huge,” Kruse said of the archive. “They’re filled with amazing material. It’s like Christmas morning every time I go in there. It’s phenomenal.”

Nearly the entire archive was opened this past summer to all researchers, except for 12 boxes that were donated in 2018 and that will be unavailable until 2020. Doar’s Watergate files will remain closed until 2024 in accordance with a law passed by Congress in 1974 stipulating that files from President Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings remain sealed for 50 years.

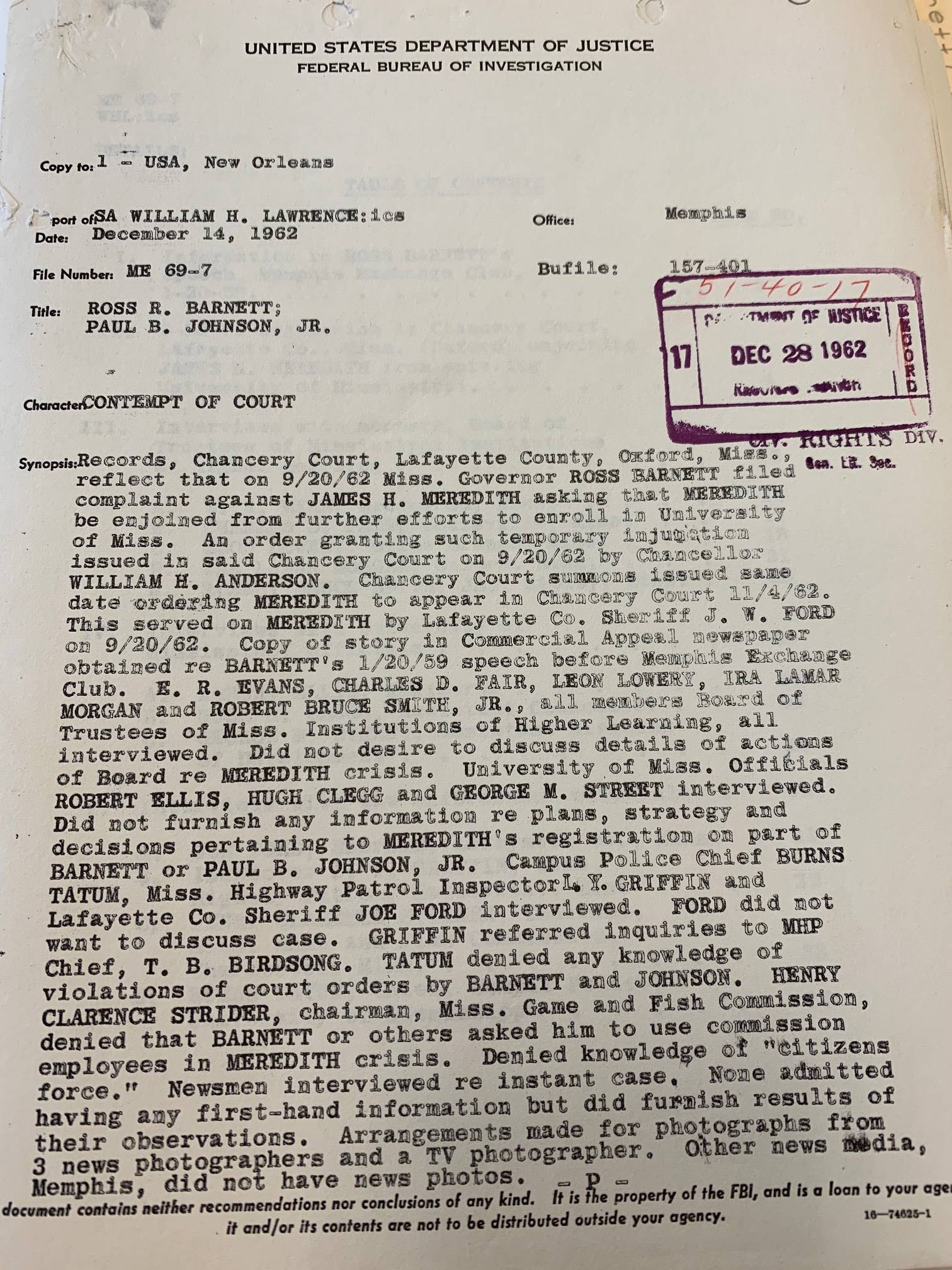

The John Doar Papers comprise 265 boxes (263.1 linear feet in total) containing depositions, court records, investigation files, photographs, correspondence and notes from throughout Doar’s career that promise to shed new light on U.S. civil rights history, as well as the history of Watergate. Pictured here is an FBI report regarding Johnson and Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett’s refusal to allow Meredith to enroll at “Ole Miss.”

Doar’s son Robert, a 1983 Princeton graduate and president of the American Enterprise Institute, said his father was appreciative of Mudd Library and Linke’s stewardship of his papers.

“He was a believer in facts and in documents and in understanding what has happened in our history, and he was a lover of Princeton and thought it was a great place for papers that could inform our understanding of history to be available to scholars,” Robert Doar said.

“Kevin is a very, very solid, good American historian, so we’re very lucky,” he added. “I think the country is going to be very lucky he chose to take this assignment on because I think he has the potential to tell the story very well. He certainly has done it with his previous books.”

Kruse said the manuscript for “The Division” is due to his publisher, Basic Books, in 2022. In the meantime, he has developed a course at Princeton based on his research, titled “The Political History of Civil Rights.” It’s a practice he’s followed with all of his books, he said. Before writing “One Nation Under God,” for instance, he taught two courses on religious conservatism.

Building a course around the institutions and partisan politics that influenced the civil rights movement was a way for Kruse to immerse himself in some of the basic literature. But also, his students’ questions have fueled his own inquiry, and the class discussions have informed how the book is taking shape.

“It’s a great way to work through some big ideas about a field with a smart group of people, and that’s who our students are,” he said. “And again, to see what they’re curious about, what they don’t understand. I take those lessons with me when I write.”

Many of the lessons of Doar’s life and example are ripe for examination. For example, Kruse said Doar reshaped the Justice Department into one of the most important agencies in the federal government at a critical time.

“It’s a reminder that institutions matter,” Kruse said. “And more importantly, that the individuals in those institutions matter.”

“The civil rights movement doesn’t turn out the way it does without people like John Doar taking this active interest,” he added. “We think about political history in terms of presidents and senators and members of Congress. This story of Doar and his colleagues in the DOJ shows that there were people in these federal agencies who really did impact the course of history and in really powerful ways.”

Linke said Doar’s role in the civil rights movement also was noteworthy because he was a Republican who was appointed by a Republican president (Dwight D. Eisenhower) and then continued through two Democratic administrations (John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson).

It was Doar’s unremitting belief in the American democratic process that sustained his civil rights work, Linke said.

“I didn’t realize he was appointed by Eisenhower because of all the work he had done under JFK and LBJ,” Linke said. “And it was because he was interested in fairness. It was a matter of fairness that people weren’t being allowed to vote or being able to enjoy the full privileges of citizenship.”

Linke said it is likely the use of the John Doar Papers will build over time. He sees the papers as an ideal resource for Princeton seniors to mine for thesis ideas. “If you’re interested in the Voting Rights Act, there’s material there,” he said. “If you’re interested in discrimination in housing or transportation or education, these are all things Doar worked on.”

Kruse’s book will be significant, but it will not be the final word on a great American life, Linke said. “There’s going to be lots of other parts of Mr. Doar's life and story and how it connects to American history,” Linke said. “Because someone probably could just write on Bedford-Stuy. And once [the files] open, someone probably could just write about Watergate. He had an amazing life.”

Kruse, who is the Old Dominion Research Professor at the Humanities Council for 2019-2020, will give a free talk about John Doar as part of the Old Dominion Public Lecture Series. Titled "The Division: John Doar, the Justice Department and the Civil Rights Movement," the talk will be held from 4:30 to 6 p.m., Wednesday, Feb. 12, at 010 East Pyne.

For more about Kruse's research and an inside look at the John Doar Papers, view a video livestream of Kruse broadcast Jan. 16, 2020 on Twitter.