Princeton undergraduates participate in the fall seminar “Crossing the Climate Change Divide” taught by Meera Subramanian (front left), an award-winning journalist and the Currie C. and Thomas A. Barron Visiting Professor in the Environmental Humanities. On Oct. 16, the students discussed the book “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right” by Arlie Russell Hochschild.

This fall, Princeton undergraduates are taking a deep dive into the climate debate in the seminar “Crossing the Climate Change Divide.”

The course is taught by award-winning journalist Meera Subramanian(Link is external), who is asking students to examine what people think about climate change — whether they accept the current climate science, reject it or are simply confused by it — and why they think the way they do.

“I’d love the students to engage in the conversation around climate change with a slightly more wide-open lens about how people are thinking about this and why people are thinking about it in the ways that they do,” said Subramanian, the Currie C. and Thomas A. Barron Visiting Professor in the Environmental Humanities in the Princeton Environmental Institute(Link is external) (PEI). She is participating in a panel titled “Breaking the Logjam” at the Princeton Environmental Forum(Link is external) on Oct. 25.

Subramanian wants the students “to engage in the conversation around climate change with a slightly more wide-open lens.”

Subramanian wants the students to use what anthropologists call an “emic,” or “insider’s,” approach — that is, taking into account a person’s words, perceptions and beliefs as main sources of information rather than adopting a potentially more objective or “outsider’s” approach. This demands that the students consider factors such as how an individual’s ideology, religion, economic level and politics impinge on a particular topic — in this case, the climate debate.

“Humans are messy creatures,” Subramanian said. “It’s not like we’re just economic creatures or just religious creatures. We are all of those things, all at once.”

She said that the climate debate is often framed as a wide gulf occupied on one side by climate “deniers” and on the other by Green New Deal “leftists.” Subramanian rejects this us-versus-them dichotomy as misleading and simplistic.

“The reality,” she said, “is that most Americans are somewhere in the middle on the climate issue. And yet we’re not often hearing those stories about the complicated ways people are thinking about climate change.”

Subramanian earned her graduate degree in journalism from New York University and has been a Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT and a Fulbright-Nehru Senior Research fellow in India. Her search for stories about the environment and the natural world has carried her all over the globe. Her writing has been published in Nature, Orion Magazine, The New York Times and NewYorker.com. Her book, “A River Runs Again: India’s Natural World in Crisis from the Barren Cliffs of Rajasthan to the Farmlands of Karnataka,” was published in 2015.

To research the climate debate in the United States, Subramanian spent 2017 into 2018 speaking to residents of rural areas who have been hit hardest by climate change.

Her interviews resulted in a series of nine articles for InsideClimate News called “Finding Middle Ground,” for which she interviewed Texas fishermen, Montana fly fishermen and Georgia peach growers, among others. The series, which was a finalist for the Scripps Howard Awards, focuses on voices from people generally assumed to occupy the right wing of the political spectrum, such as Christian evangelicals and working-class populations in rural West Virginia. Her work for this series forms the basis of her seminar at Princeton.

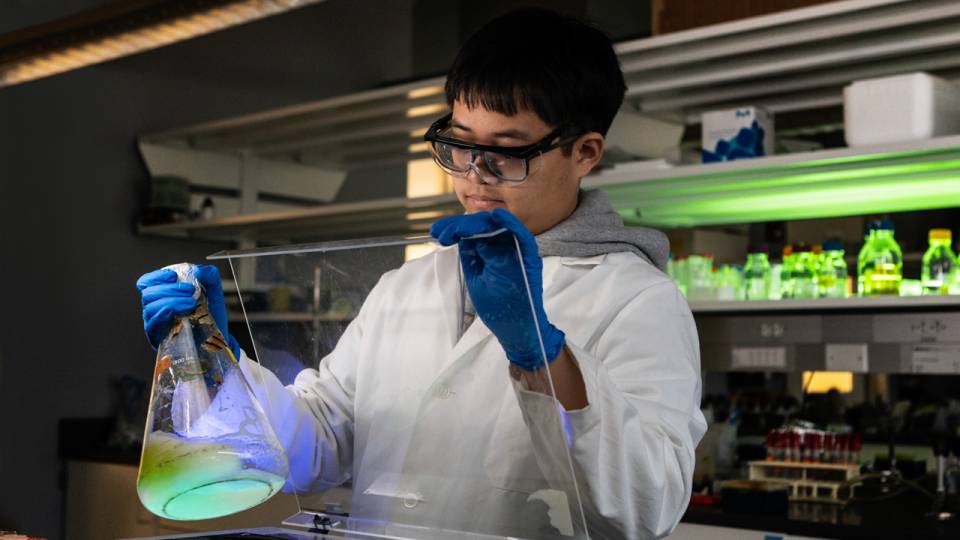

Over an afternoon in Jones Hall, students discuss the climate debate and why people hold such divergent viewpoints on the subject.

The class also draws on a host of books, articles and YouTube videos that explore the debate from multiple perspectives. On the syllabus are: “The End of Nature” by Bill McKibben, “How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate” by Andrew Hoffman, “Merchants of Doubt” by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, and “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right” by Arlie Russell Hochschild.

The students began their Oct. 16 class by engaging in a lively discussion of Hochschild’s book, which focuses on a conservative-leaning community in Louisiana. Many of its members are Tea Party supporters who voted for Donald Trump in the last election and take a skeptical view on human-induced climate change.

Seated at the table together in Jones Hall, the students acknowledged that it tends to be easier to gain understanding of others’ viewpoints through face-to-face communication.

One student said, “Interacting with people person-to-person is very important to create a level of empathy. I think it’s a lot easier to ‘otherize’ when you haven’t interacted.”

In a role-playing exercise, students adopted the “emic” approach. In teams of two, one student took on the viewpoint of a person in the book while the other student conducted an interview, asking questions covering a range of topics, including views on climate change.

During one exchange, a student impersonating one of the book’s characters was asked about her family background. She said she was from a family with ties that went back to the coal industry. The interviewer’s father had worked as a logger, so she understood the nature of hard, dangerous work.

As part of a presentation on seeing another’s perspective, students superimpose sketches of the faces of police officers and alleged perpetrators to suggest reaching common ground as a way of building empathy.

The discussion about similar upbringings resonated between the pair. “I feel that it was an easy way to shortcut to find common ground,” said a student. “You can’t start with politics if you want to get to common ground.”

The students generally agreed the assignment was awkward at first.

“It was difficult putting someone else’s words in your mouth,” one student said. As the pairs chatted, however, they said they began to see the value of finding parallels between people with whom you think you have nothing in common.

“It’s easier to talk to people if you can find a shared background,” another student added.

Many of the students said they chose the class because they were interested in climate change and wanted to understand why there were conflicting views about it.

“It’s such a polarized issue,” said sophomore Dani Ball, “and I’ve never understood why we can’t work toward a solution and get something done.” But she is aware that other people have different views and added that working toward understanding people on both sides of this issue is a necessary step forward.

“After reading [Hochschild’s] book I feel like I understand a different perspective, and that for me is exciting,” said junior Raya Ward. “The class is a great practice in empathy and understanding people.”