Researchers at Princeton University calculated flood risks for 171 counties across New England, the mid-Atlantic, southeast Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. They found that what used to be considered 100-year floods will occur far more often depending on the location. The relative contributions of rising sea levels and changing storms differed according to the area of the country being studied. In northern areas, sea level rise is a major contributor to increased flooding, while changing storm dynamics are relatively more important in southern areas.

A 100-year flood is supposed to be just that: a flood that occurs once every 100 years, or a flood that has a 1% chance of happening every year.

But Princeton researchers have developed new maps that predict coastal flooding for every county on the Eastern and Gulf Coasts and find 100-year floods could become annual occurrences in New England; and happen every one to 30 years along the southeast Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico shorelines.

“The historical 100-year floods may change to one-year floods in northern coastal towns in the U.S.,” said Ning Lin, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering(Link is external) at Princeton.

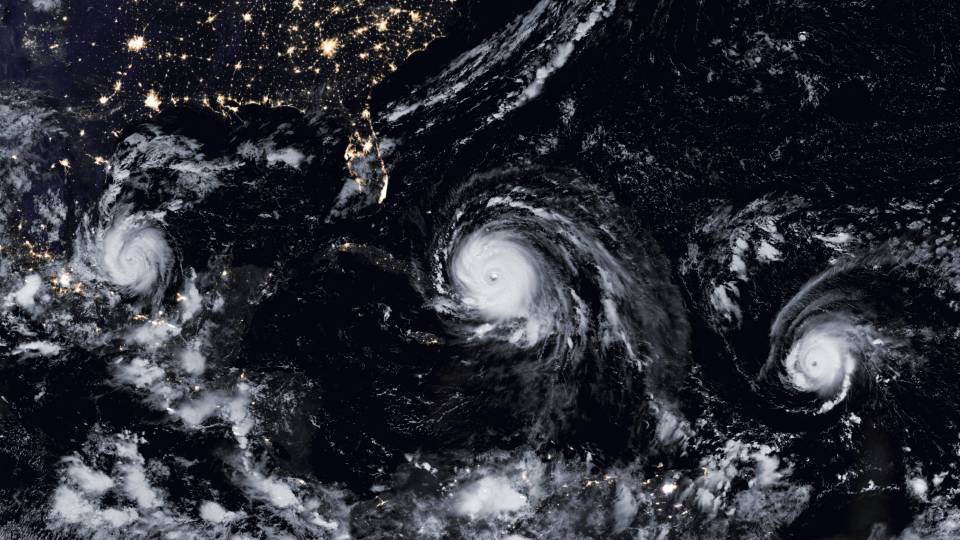

In a paper(Link is external) published Aug. 22 in the journal Nature Communications, researchers combined storm surge, sea level rise, and the predicted increased occurrence and strength in tropical storms and hurricanes to create a map of flood hazard possibility along the U.S. East Coast and Gulf of Mexico. Coastlines at northern latitudes, like those in New England, will face higher flood levels primarily because of sea level rise. Those in more southern latitudes, especially along the Gulf of Mexico, will face higher flood levels because of both sea level rise and increasing storms into the late 21st century.

“For the Gulf of Mexico, we found the effect of storm change is compatible with or more significant than the effect of sea level rise for 40% of counties. So, if we neglect the effects of storm climatology change, we would significantly underestimate the impact of climate change for these regions,” said Lin.

The study uses the latest climate science to examine how tropical storms will change in the future, said Reza Marsooli, assistant professor of civil, environmental and ocean engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology, who worked on the study while a research scholar at Princeton. The storm data, in turn, was integrated with sea level analysis. Marsooli noted that the study combines multiple variables that are typically addressed separately. For example, the new maps use the latest climate science to look at how tropical storms will change in the future instead of what they are right now, or even looking backwards at previous storms, as federal disaster officials do to build their flood maps. These data, in turn, are integrated with sea level analysis.

The researchers hope that creating more accurate maps — especially those that are customized according to local conditions down to the county level — will help coastal municipalities prepare to face the effects of climate change head on.

“Policymakers can compare the spatial risk change, identify hotspots and prioritize the resource allocation for risk reduction,” said Lin. “Coastal counties can use the county-specific estimates in their decision-making: Is their risk going to significantly change? Should they apply more specific, higher-resolution data to quantify the risk? Should they apply coastal flood defenses or other planning strategies or policies for reducing the future risk?”

Kerry Emanuel, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Atmospheric Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Kairui Feng, doctoral candidate in civil and environmental engineering at Princeton, are also authors on the paper.

This research was funded by National Science Foundation and the Princeton Environmental Institute(Link is external) at Princeton.