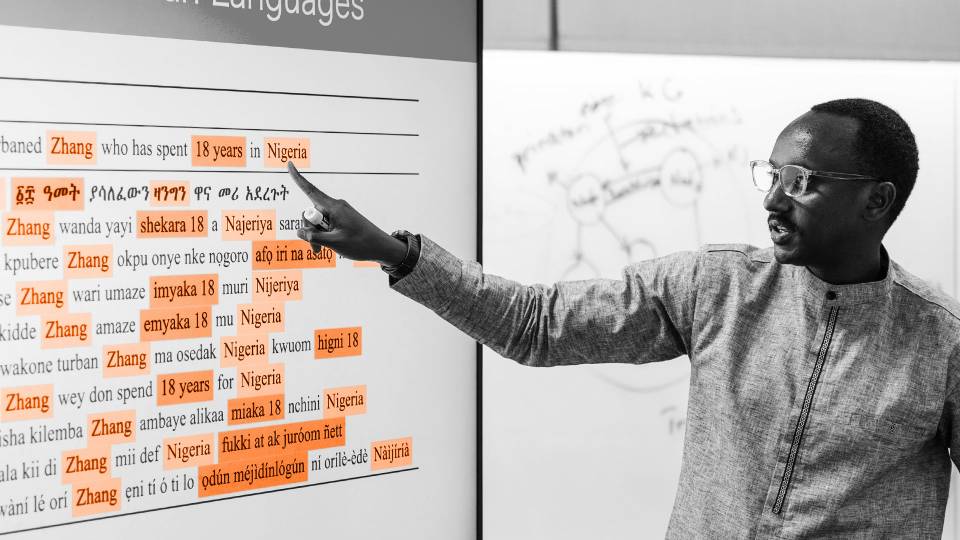

What factors make a political movement successful? Can internet searches reveal patterns of economic inequality? How do racial and gender biases influence health outcomes?

For social scientists addressing these questions, troves of data from social networks, news media and online transactions bring unprecedented opportunities, along with new ethical and technical challenges.

Margaret Ng of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (back, left) and Yuan Yuan of MIT (back, right) present and discuss their research as part of the Summer Institute in Computational Social Science, held June 16-29 at Princeton University. Co-organized by sociology professor Matthew Salganik (front, left), the program helps early-career researchers in sociology, economics and other fields make the most of digital data. Also pictured is Tom Wolff (front, right), a Ph.D. student at Duke University who served as a teaching assistant for the program.

The Summer Institute in Computational Social Science, held June 16-29 at Princeton University, helps early career social scientists and data scientists make the most of digital data. Participants receive training in ethics and research approaches, and begin cross-disciplinary collaborations based on their interests.

“It’s an opportunity to bring together graduate students, postdocs and junior faculty to get exposure to new ideas and new people,” said Matthew Salganik, a professor of sociology at Princeton who co-founded the annual institute in 2017 with Duke University sociologist Christopher Bail. “It’s also a chance for us to create a community of computational social scientists that’s interdisciplinary and that has norms that are in the best interests of society and science.”

This year’s 29 participants came from fields including political science, legal studies, economics and epidemiology. Because the participants' familiarity with data science and social science varied widely, Salganik and Bail curated a set of pre-arrival activities to give all participants basic knowledge in both areas.

During the first week of the program, Salganik and Bail gave lectures on ethical standards and challenges in computational social science, as well as technical aspects of data collection, text analysis and digital survey design. Each day the participants broke into small groups for activities that expanded on the ideas presented in the lectures — for example, comparing two text analysis methods to search for associations between President Donald Trump’s tweets and his approval ratings.

The program also hosted guest speakers, including Chris Wiggins, an applied mathematician at Columbia University who serves as chief data scientist at The New York Times, and Alondra Nelson, president of the Social Science Research Council, who recently joined Princeton’s Department of Sociology and the Institute for Advanced Study’s School of Social Sciences.

Participants in the Summer Institute in Computational Social Science discuss research projects begun during the program.

When they launched the institute in 2017, Salganik and Bail quickly realized there was a greater demand than they could meet with a single two-week program in one location. They made the lectures and guest talks available by livestream and archived video, and they also sought a way “to create mini communities for all the people who were not able to be with us,” said Salganik.

The following year, the program’s alumni set up seven partner locations around the world. This year, in addition to the Princeton institute, partner programs were held in 11 other locations spread across seven countries.

Participants at the partner locations watched the livestreams together and submitted questions for the guest speakers. All teaching materials were made open-source, and the program’s teaching assistants — sociology graduate students from Princeton and Duke — supported participants at all sites as they practiced new concepts and embarked on their own research projects.

“We think this model of having [program] alums create partner locations is a great way for us to increase the impact of the program and increase access to this knowledge,” said Salganik.

Also critical to the program’s success, said Salganik, is its community-driven approach to generating and pursuing new research ideas. The second week began with a process Bail developed called “research speed dating.” During this process, participants proposed broad research topics and other participants indicated their interest in these topics. Next, these data were used to form maximally similar groups and then maximally dissimilar groups for face-to-face discussions during which the broad ideas were refined into specific research projects. At the end, participants proposed their research projects to each other and then joined the project of their choice.

One team examined the effects of live online commenting on consumers of political media. Another devised experiments to test the hypothesis that people are more likely to help others whose facial features are similar to their own. A third group used anonymized data on transactions from the home-sharing website Airbnb to investigate changes in users’ behavior after the company implemented an anti-discrimination policy.

The research teams receive small grants during the program and are encouraged to apply for additional funding to continue their collaborations. Findings from several projects initiated during the 2017 institute have now been published in academic journals.

“We’ve found that the participants learn a lot from working with each other — often much more than anything that we can teach them,” said Salganik. “The work that comes out of the summer institute is distinctive because these collaborations would not have happened otherwise.”

During a break between research presentations at the Summer Institute in Computational Social Science, Professor of Sociology Matthew Salganik talks with participants Sarah Rezaei of Utrecht University (left), Nynke Niezink of Carnegie Mellon University and Florianne Verkroost of the University of Oxford.

The research project on Airbnb and discrimination, for example, is a collaboration between a political science Ph.D. candidate from the United States, a postdoctoral fellow in economics from Switzerland and a professor of legal research from the Netherlands.

“We face common problems in our research,” said Malka Guillot, the economics researcher, who applies computational approaches to study taxation and inequality at ETH Zurich. Guillot said she found it rewarding to be part of a program where “two communities converge” — social scientists seeking to further their knowledge of data science, and data scientists looking for new ways to apply their methods.

Yuan Yuan, a Ph.D. student at the MIT Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, joined the research project on facial similarity and reciprocity. Yuan, whose background is in computer science and economics, said he appreciated the opportunity “to get involved with a lot of social scientists — to talk with them and learn their philosophies.”

“It’s one of the most exciting times to be a social scientist,” said Salganik. “The transition from the analog age to the digital age means that so much new data about human behavior is being created, and we can measure societies in ways that were never possible before.”

Salganik said he expects that the institute’s alumni will continue to expand its network of partner locations in 2020, when the main program will be held at Duke.

The Summer Institute in Computational Social Science is sponsored by the Russell Sage Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.