In her acclaimed 2018 book, “Why Religion? A Personal Story,” Elaine Pagels, the Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion, interweaves her own account of unimaginable loss with the scholarly work that she loves, examining the spiritual dimension of human experience.

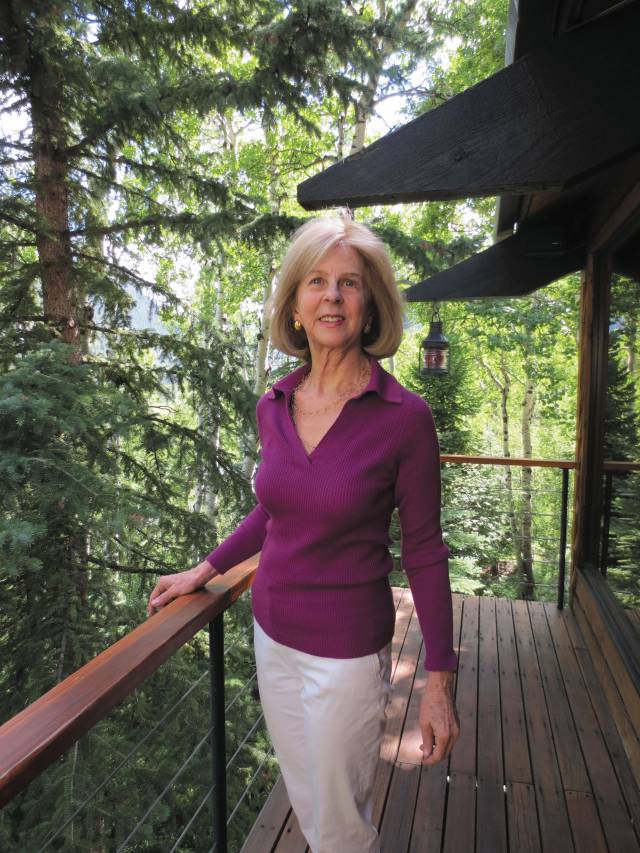

Elaine Pagels

Her son, Mark, born with a hole in one of the walls of his heart that was repaired in open heart surgery at age 1, died at 6 ½ from a fatal condition called pulmonary hypertension. Her husband, the theoretical physicist Heinz Pagels, died just over a year later in a mountain climbing accident. Pagels has two grown children — a girl, adopted as an infant when her son was alive; and that girl’s brother, adopted after her son’s death. In “Why Religion?” Pagels looks at her own life to address questions of the persistence and nature of belief and why religion is still around in the 21st century.

Pagels will hold a conversation about the book with Wallace Best, professor of religion and African American studies, at 6 p.m. Monday, April 29, at Labyrinth Books, 122 Nassau St.

An authority on the religions of late antiquity, Pagels joined the Princeton faculty in 1982, shortly after receiving a MacArthur Fellowship. She was awarded a 2015 National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama and received Princeton’s Howard T. Behrman Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Humanities in 2012.

Pagels has taught courses ranging from the freshman seminar “Who Is — Or Was — Jesus?” to graduate courses in Greco-Roman religions.

Her books bring a fresh perspective to the history of Christianity. “Gnostic Gospels” won the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award and was selected by the Modern Library as one of the best 100 English-language nonfiction books of the 20th century. “Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas” was a New York Times bestseller. Other books include: “Revelations: Visions, Prophecy and Politics in the Book of Revelation”; “Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity,” co-authored with Karen King, the Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard University; “The Origin of Satan”; and “Adam, Eve and the Serpent.”

In “Why Religion?” you write, “I didn’t want to write just a grief memoir, I wanted to write about how hearts can heal and how we can recover.” The response to your book shows many people wish to know the same. What has it been like to connect with readers around this question?

Everybody has grief. I love talking to people about this partly because one of the issues that comes up a lot is the feeling of guilt. A psychiatrist would call it survivor's guilt. It doesn't matter if it's [the death of] your parents or a partner or a friend. But with a child, it’s huge. Your responsibility is to keep that child alive; that's primary. And if you can't do that, you fail. That's how it feels. And people feel guilt with other losses, too, it's almost a reflex in the culture. You think guilt is a pretty awful feeling but what’s worse is this sense that you can't change it, you can't do anything.

Adults are used to being in control of things. The night after our son died, my close friend who was his godmother said, “Well, if you had anything to do with this, it wouldn't have happened this way,” and I thought, well, that's kind of obvious isn't it? And then, I thought, yes, that's right. If I'd had any input, it wouldn't have happened this way; it was beyond my control. That's a real confession of helplessness, but it's also a recognition of the truth. And it's also a relief.

In her newest book, Elaine Pagels interweaves her own account of unimaginable loss with the scholarly work that she loves, examining the spiritual dimension of human experience.

The deaths of your son and husband took place more than 30 years ago. Why write this book now?

I was concerned about writing something this personal. It's not something scholars do. But the response of people has been absolutely amazing, including my colleagues, because in the book, it's not about a personal story, it's weaving in the work we do. I like to say, we work on these texts and they work on us. Writing the book took seven years — since my children have been out of the house. Before that I was engaged full-time in my research and teaching and I was a single mother of two. It was hard.

So, I had finally time and in a way the necessity to go back and allow those feelings to return. I feel much freer now that I've done that. Because if you bury things that you think you can't live through, you just ignore them. The Gospel of Thomas [one of the Gnostic Gospels] says: "If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you what you do not bring forth will destroy you." I think that people who keep secrets buried because they're too shameful, too sad or too distressing, but then are able to simply allow those secrets to be there — then they're not alone with that. I needed to do that.

An important part of your journey in becoming a scholar was the discovery of these “secret” Gnostic Gospels as a graduate student at Harvard University. What are they?

This is a library of over 50 ancient gospels and other sources that claim to communicate teachings and relationships between Jesus and his disciples. They were discovered in 1945 by an Arab peasant in Upper Egypt — 13 papyrus books, bound in leather, inside an earthenware jar, almost a meter high. But the people who had access to the texts were keeping them secret because they didn't want other people to publish them. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the texts became more accessible.

We were pioneers in something that for 2,000 years had been secret, heretical, weird, poisonous, terrible stuff. We look at these texts and say, wait a minute, this is really interesting. Christianity is usually pictured as a bunch of beliefs — Do you believe in God? Do you believe in Jesus? When you look at [the Gnostic Gospels], you see it's a wide-ranging collection of stories, traditions, sayings, rituals, music, prayers, poems, dances — Jesus dances with his disciples — that articulate and express so much about the human condition.

How has working on these texts excited you as a scholar?

For me, there’s a big shift that’s taken place since I’ve worked on these. In the New Testament we have very small sources — Mark is 17 pages, Matthew and Luke are extensions of Mark, it's the same story just repeated with other stuff included, and John is kind of an outlier, as far as I'm concerned, and doesn't tell us much about Jesus of Nazareth. So, we didn't know very much and yet this huge tradition has grown out of it. It's like we thought of Christianity as one single little stream but now the dam bursts and you have all this other information, which puts it in a very human context. That's what I like. And that's changed everything.

What resonated with you about revisiting these gospels after your loss?

It was really a sort of vision I had, a sense of the connectedness of all beings and I realized that that was a very fundamental theme [of these gospels]. Christianity as we know it talks about connectedness between Christians within churches and for other people outside the church there is no salvation. The secret gospels talk about our connection not only with all humans but with all that is: rocks, animals, stars, trees. It spoke to me much more — and it still does. And these stories are so beautiful. These traditions weren't doctrines, they were stories — the story of Jesus, the story of Moses, the story of David, the story of Job. These are all stories and that's what the Hebrew Bible is primarily, and wisdom sayings. The Gospel of Thomas is all wisdom sayings.

You call your work — teaching and research — “a kind of yoga.” How so?

Yoga is about opening the heart. It is also a practice that challenges me, that sharpens understanding, that increases flexibility. And my teaching and research does that too. It opens up the questions that I reflect on.

What is one piece of advice you would want to share with female graduate students and early-career academics — in any discipline?

Trust yourself and do not allow other people to take you off course either in terms of what you want to study or what you dare say about what's going on. Write what you want to write. And take it where you need to take it.

What are you hopeful about?

Although my marriage was only 22 years, it had the gift of showing how wonderful it is to share such a connection with someone you love — it was the happiest time of my life. And even now I think, it can happen again. Who knows? It could. And I'm rather hoping so.