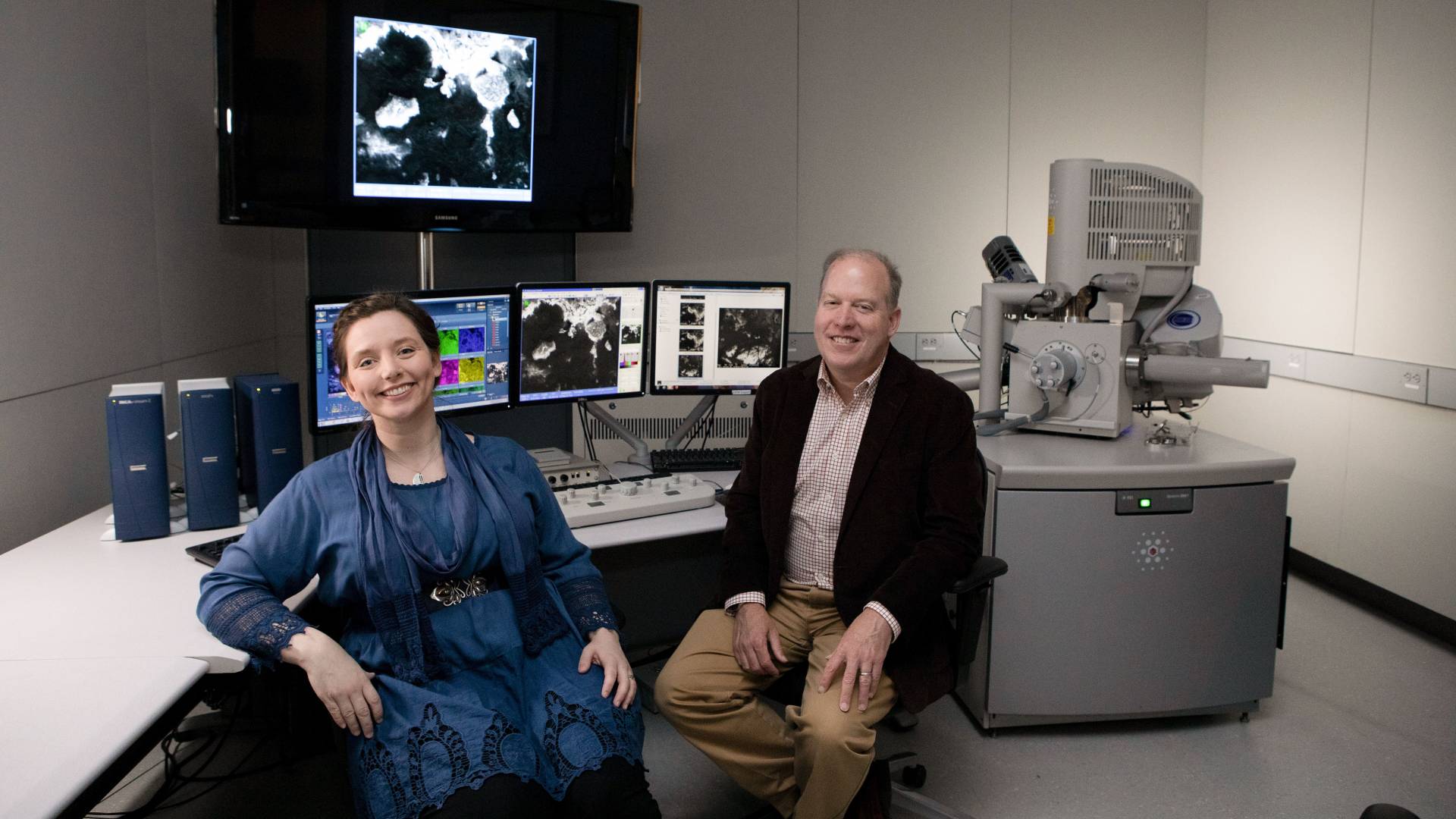

Princeton researchers Rachel Selinsky, left, and Professor Thomas Conlan, right, are using modern materials analyses to learn about medieval metallurgical practices in Japan.

Thomas Conlan fiddled with a strange, brownish-black rock on his desk. For centuries, people had considered the piece of rubble worthless, but it is priceless to Conlan’s research.

The lumpy rock is a sample of slag, the material left over after heating ore to extract valuable metals. With researchers from art, engineering and materials science, Conlan is exploring whether these discarded scraps can fill gaps in early Japanese history.

Conlan, a professor of East Asian studies and history, hopes to use the mining waste to learn about the political and cultural climate of Japan in the eighth to 18th century CE, a period for which written records are sparse.

Much of Conlan’s slag comes from the smelting of copper, a metal that played an important role in historical trade, monuments and coinage. “We know there was an incredibly vibrant process of metallurgy in the past,” Conlan said. “They were mining tons of this stuff, but there’s nothing really written about it.”

Some products of these early copper mines can still be seen today. The world’s largest bronze Buddha, located in Nara, Japan, dates from 745. Its construction required nearly 490 tons of copper from a nearby mine, as described in documents from that period. But from the 10th to the 16th century, very few records discuss mining, leading researchers to wonder whether metallurgy declined or was simply not documented.

This lack of textual records can sometimes skew historians’ perspectives, Conlan said. “Historians have overestimated the importance of rice and agriculture,” he said. “And they have underestimated the importance of mining and trade.”

Conlan hopes to correct this imbalance by probing the microscopic structure of slag. He obtained 30 or so samples, dating from 700 to 1700, from colleagues in Japan. Using state-of-the-art methods with support from the David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Project fund for innovation in the humanities, his team wants to learn the techniques of medieval metallurgists, including what additives were mixed in the metals, what temperatures were used and how the materials were refined.

Japanese medieval metallurgical practices are depicted here in the book "Kodō zuroku" by the Sumitomo Family. The book dates to 1795 and describes how to extract copper from ore.

Conlan’s collaborators on the project are Howard Stone, the Donald R. Dixon ’69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering; Nan Yao, a senior research scholar with the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials (PRISM) and director of the Imaging and Analysis Center; and Rachel Selinsky, an associate research scholar in chemical and biological engineering. Conlan was also advised by Craig Arnold, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and the director of PRISM, and Bruce Koel, a professor of chemical and biological engineering.

At a recent meeting to discuss the project, the researchers huddled around a desk in Conlan’s book-lined office, far from the sterile labs and whirring machines in the imaging center.

Material scientists have analyzed slag in the past, but the researchers think this is the first time that slag has been used to investigate a region’s history.

“There’s a kind of detective problem here,” Stone said.

“It’s like trying to figure out a puzzle without having all the pieces,” Nan said.

“It’s like figuring out what a forest looked like from 30 leaves,” Conlan said.

Selinksy is in charge of conducting the experiments, which include identifying a sample’s constituent elements by shooting X-rays at it and measuring what is emitted in response. So far, the data suggest that Japanese metallurgists did not add any ingredients, such as calcium, to improve the extraction of copper.

The team has now turned their attention to the slag’s crystallographic composition, using different tools to see if the material’s history is locked in its structure.

If their work does identify improvements in metallurgy through time, the research could fundamentally change the way historians not only look at early Japan, but how they view the historical role of copper worldwide. Many early economies depended on copper production, and these techniques may well shine light on other ancient civilizations that left few written records.

This article was originally published in the University's annual research magazine Discovery: Research at Princeton.