David P. Billington, whose scholarship found elegance and beauty in practical works of engineering, died in Los Angeles on March 25. He was 90.

David Billington

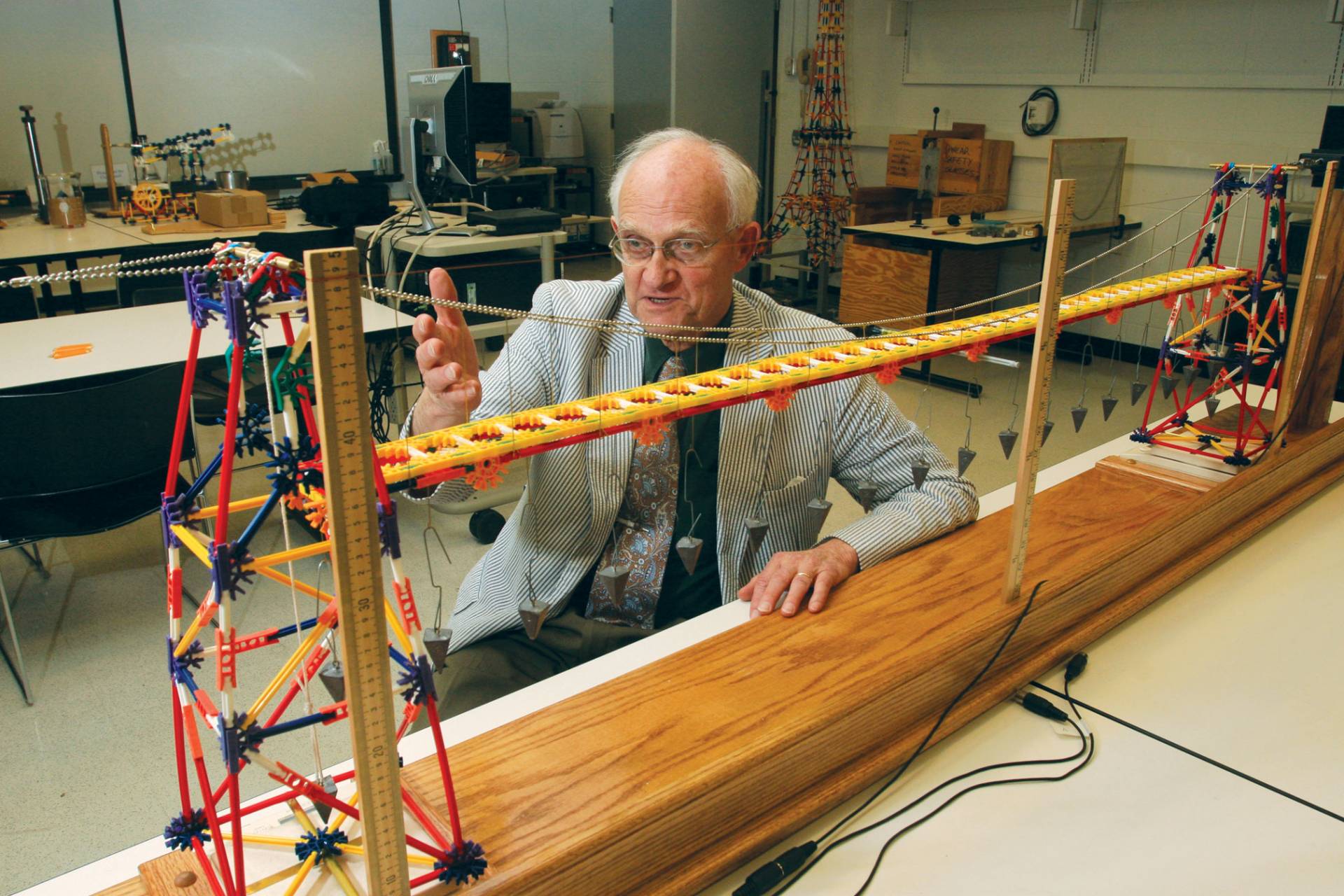

Billington, the Gordon Y.S. Wu Professor of Engineering, Emeritus, at Princeton University, pioneered the discipline of structural art, which evaluates artistic expression under the practical constraints of engineering. His work inspired a generation of scholars and redefined the consideration of great engineering works from bridges to buildings.

"The disciplines of structural art are efficiency and economy, and its freedom lies in the potential it offers the individual designer for the expression of a personal style motivated by the conscious aesthetic search for engineering elegance," Billington wrote in his 1983 book “The Tower and the Bridge.”

In 10 books and scores of journal articles, Billington explored the works of builders and innovators with a particular focus on bridges and thin, graceful structures. Michael Littman, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and a longtime colleague, said Billington joined a historian’s breadth of knowledge and an engineer’s disciplined focus.

"He asked big questions about engineering, how it fit into society and how it changed the world," said Littman, who now teaches Billington’s course "Engineering in the Modern World" at Princeton. "I thought it was a perspective that is much needed and is usually absent from most engineering education."

Billington joined the Princeton faculty in 1960 after working for the consulting engineering firm Roberts and Schaefer in New York City. As a young professor, he was asked to lecture architecture students about engineering principles. In a 2003 article in the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Billington recalled how the students grew bored and asked to "study something beautiful." They showed him photos of bridges that swept like concrete ribbons across gorges in Switzerland. Billington was fascinated and began his foundational study of the work of the Swiss engineer Robert Maillart. It was the beginning of his lifelong work to recognize engineering as an artistic as well as a technical discipline.

"Maillart was an artist," Billington wrote in the preface to his 1990 book Robert Maillart and the Art of Reinforced Concrete. He noted that "his major works are exemplars of a new art form prototypical of the 20th century."

Billington went on to apply the measure of art found within the strict boundaries of engineering to structures as varied as Othmar Ammann’s George Washington Bridge in New York and Félix Candela’s Chapel Lomas de Cuernavaca in Mexico City. Billington also applied his scholarship to his teaching methods. Using an approach inspired by art historians, he built lectures around the works of individual designers with a clear understanding of the context of their development.

"Billington was magisterial in the lecture hall," said John Ochsendorf, who earned his master's degree at Princeton in 1998 and is now the Class of 1942 Professor of Architecture and professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "We were all spellbound by the force of his arguments, the breadth of his cultural references, the beauty of his images, and of course, the wit of his jokes. To attend a Billington lecture was to be changed forever."

Billington’s classes became enduringly popular. It has been estimated that roughly one in five Princeton students attends either "Engineering in the Modern World" or "Structures in the Urban Environment" during their time at the University. In the classes, students are challenged to evaluate works in terms of their scientific, social and symbolic contributions. They learn to apply Billington’s standards of efficiency, economy and elegance.

"Efficiency means minimal materials, economy means minimal cost," Littman said, "elegance means maximum expression."

Eric Hines, a principal at LeMessurier engineering in Boston and a professor of practice at Tufts University who earned his BSE at Princeton in 1995, decided to pursue engineering after taking "Structures in the Urban Environment" at the end of his freshman year. He said Billington showed students that engineering could be more than simply functional.

"This was in line with Billington’s thesis of structural art — the design comes out of the engineering imagination; the aesthetics and the design concept are the same thing," he said. "You really had to understand structures at a fundamental level to understand that."

For Billington, the engineering principles behind a structure were the first step in understanding the importance of the work. He often taught design through simple formulas. In "Engineering in the Modern World," for example, he used the formulas for the horizontal and vertical reaction forces to teach students about design choices in Thomas Telford’s Menai Straits Bridge in the United Kingdom. Billington used a classic formula to show students that a suspension bridge with high towers and a deeper cable sag would require lower strength cables to support the load. The cables would cost less, but the tall towers would cost more. A flatter, shallower bridge would require higher strength cables. Here the cables would cost more, but the shorter towers would cost less and give a more elegant profile. It was these types of calculations that governed Telford’s design, which created the world’s longest span in 1826. Telford’s bridges are beautifully light.

"He made design factors understandable through basic engineering formulas," Littman said. "I know of no scientist or engineer that looked at formulas in the way that David did."

Maria Garlock, who now teaches Billington’s "Structures in the Urban Environment" class, said Billington was a close friend and mentor as well as a colleague. In a preface to a book she co-wrote with Billington on the engineer Candela, Garlock wrote that his example “reminded me of why I became a structural engineer and renewed my enthusiasm and pride in this profession that I have chosen.”

In addition to teaching together and co-writing books, Garlock and Billington developed a 2008 exhibition on Candela’s work in cooperation with the Princeton University Art Museum. Candela’s work often involved constructing thin concrete shells over scaffolding known as falsework. A saddle-shape form, called a hyperbolic paraboloid, minimized stresses and provided a stiff and strong structure. The result was a supremely efficient structure with sweeping, graceful lines — a picture of efficiency, economy and elegance. Besides introducing Candela’s work to a larger public, the exhibition served a teaching purpose. Students visited Candela’s structures and evaluated them in papers that were featured in the exhibition.

“He was always encouraging, a fan, someone at your side saying you could do this,” said Garlock, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of the Program in Mechanics, Materials and Structures. “That is one of the reasons why he had so many students who are so grateful to him.”

Sinéad Mac Namara, a 2002 alumna, said Billington taught her that "engineering was an art unto itself."

"He was a fierce advocate for his students," said Mac Namara, an associate professor at Syracuse University’s School of Architecture and College of Engineering. "He was a champion, in particular, for women in engineering."

Abbie Liel, also a 2002 alumna and an associate professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder, remembered Billington as a mentor who consistently made her "feel like talking to me was the most important thing he had to do all day."

"If I can do for one student as much as he did for me, my career will have been a success," she said.

David Perkins Billington was born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, on June 1, 1927. Following service in the U.S. Navy, he graduated from Princeton with an engineering degree in 1950. With a Fulbright Scholarship to study structural engineering, he spent two years in Belgium, where he met and married Phyllis Bergquist, a Fulbright Scholar in music. He joined the Princeton faculty in 1960 and was named the Gordon Y.S. Wu Professor of Engineering in 1996. He served as director of the Program on Architecture and Engineering from 1990 to 2008. He twice was a visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and held summer visitor positions at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Billington transferred to emeritus status in 2010.

Among other honors, he was a member of the National Academy of Engineering and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1999, the journal Engineering News Record named him one of the top five educators in civil engineering since 1874. In 2003, he received the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teaching Scholars. At Princeton, he was a multiple winner of the Engineering Council’s Excellence in Teaching Award and an honorary member of the classes of 1979 and 1995. He received the President’s Distinguished Teaching Award in 1996 and was awarded an honorary degree at Commencement in 2015.

Billington’s principal summer activity for many years was to photograph bridges, often assisted by his children. He enjoyed concerts with his wife, Phyllis, and both had many friends in the Princeton community. He is survived by his brother and sister-in-law, Librarian of Congress Emeritus James H. and Marjorie Billington; his sister-in-law Lynn Billington; six children (David Jr., Elizabeth, Jane, Philip, Stephen and Sarah); and 11 grandchildren. The family asks that donations in lieu of flowers be made to Arm in Arm, formerly the Crisis Ministry of Mercer County.

View or share comments on a blog intended to honor Billington's life and legacy.