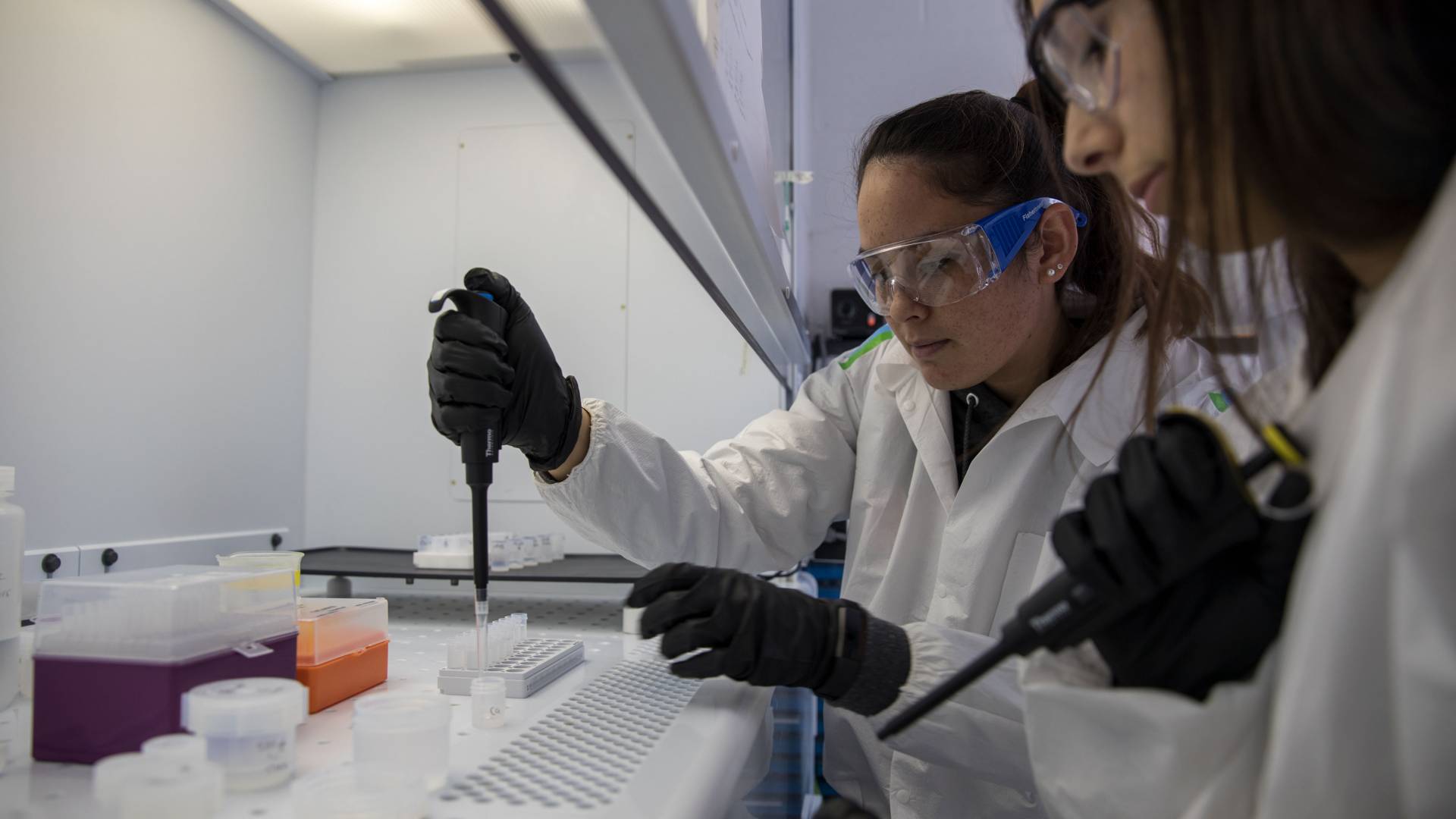

The project "Urban Tap Water and Human Health" led by Princeton University professors John Higgins and Janet Currie combines science with community service. Funded by PEI's Urban Grand Challenges program, the initiative engages students such as juniors Kimberly Peterson (left) and Rebecca Mindel (right) through Higgins' spring course, "Geochemistry of the Human Environment," where students learn scientific techniques to help provide Trenton residents with free lead-contamination testing.

On a hot morning last August, Princeton University rising sophomore Young Joo Choi crouched in the receding shade of a house in West Trenton, New Jersey, firing gamma rays into the dirt along the foundation.

It's here that soil contamination from lead-based paint tends to be highest.

Choi used a handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) reader, an instrument that measures the most minute concentrations of elements in the object or substance it's pointed at. Behind her, rising senior Elizabeth Stanley waited to record the readings. As the whir of cicadas overtook the quiet residential street, Stanley talked with Hinake Kawabe, a rising junior, about the water samples they had collected inside, as well as their XRF readings from the home's doors, windows and lower interior walls.

After Choi reported that the soil was negative for lead contamination, the three packed up their samples and equipment for the trip across town to the next house as the heat and humidity of midday set in.

Choi, Kawabe and Stanley were the first Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) summer interns to work on the project "Urban Tap Water and Human Health," a larger effort funded by PEI's Urban Grand Challenges program that combines science with community service.

Led by John Higgins, assistant professor of geosciences, and Janet Currie, the Henry Putnam Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, the project, which began in 2016, aims to measure the level and source of lead contamination in Trenton homes, then eventually see how those data correlate with childhood health and development. The project engages students through the spring course Higgins teaches, "Geochemistry of the Human Environment," which is an offshoot of the tap-water project and is now in its second semester.

Meanwhile, students help provide free lead-contamination tests for Trenton residents. Students in the course work with the Trenton-based nonprofit organization Isles Inc. to collect samples directly from the homes of Trenton residents, or to analyze water samples Isles provides to Higgins' lab. At the same time, they learn to use scientific techniques and tools such as mass spectrometry and XRF.

"This has taught me that it's possible to have a good combination of lab work and fieldwork — this internship has been a great mixture of both," Choi said outside the house in West Trenton.

(The Trenton group's presentation for the 2017 PEI Summer of Learning Symposium is available online.)

"It's been interesting to see an intersection of science and how it actually affects people," added Stanley, who like Choi and Kawabe segued into the internship from Higgins' course. "In the lab, we can run a test and know what the right answer or approach is. Out here, there are so many other factors and challenges at work."

Sophomore Peter Schmidt (front) and Mindel (rear) work with graduate student Jack Murphy (middle) to analyze tap-water samples from the mass spectrometer in order to assess the accuracy and precision of the chemical measurements. Results from the class are used to advance the overall project. As of November, Princeton students had analyzed around 750 water samples from 245 Trenton households. The average lead content was 2.5 parts-per-billion (ppb) with 3.5 percent of the houses exceeding the federal standard of 15 ppb. The highest lead content encountered was 147 ppb.

In Higgins' lab, students use chemical analyses to quantify local sources of lead contamination. Testing for lead in tap water is typically done at the central-distribution level rather than at the tap, Higgins said. This means that lead entering a household from corroded pipes or water mains can go undetected.

His students measure 15 different elements in tap water that can be used to develop a "fingerprint" of where the lead is coming from, such as from the water main or from within the house. For example, the presence of cadmium or zinc can signify that the roots of the contamination are solder and pipe fittings in a house's plumbing.

"You need fairly complicated instruments to do these measurements well — it's not common overall," Higgins said. "It's about being able to put your finger on what the source of the contamination is. The hope is to provide some insight into how we can remediate the problem more effectively."

Sophomore Peter Schmidt, a prospective concentrator in Spanish and Portuguese and environmental studies who is taking the course this semester, likes that his work with Higgins could help address an immediate environmental problem. Schmidt was struck by a recent class in which Currie talked about the correlation between misbehavior and high levels of lead in a child's blood.

"I'm more interested in the story side of things — basically, there are these poisons and some people are at higher risks than others for reasons I don't entirely understand," Schmidt said.

"I can see myself doing a project about people affected by lead and I think that means testing for lead and its sources," he said. "A long time ago, we built our cities in a way that was harmful to our health and now the people dealing with it are the ones who are least able to. That interests me because it shouldn't be that way."

For a class in March, Schmidt and his fellow students were in a Guyot Hall clean lab preparing samples for the mass spectrometer. They tested tap water from houses in Trenton and learned how to assess the accuracy and precision of the chemical measurements.

Results from the lab will be used in the overall project, said Jack Murphy, a graduate student in Higgins' lab who works with students in the lab and in Trenton. "These students are producing new data that we're learning from — these are not labs that have been done over and over," he said.

"The work students do on this project helps them see an application of laboratory science to community engagement," Murphy said. "We use the same methods to measure the chemistry of tap-water samples that I use to measure the chemistry of rocks millions of years old. The students enjoy working with our partners in Trenton. It feels satisfying to help people get the information they need to keep themselves, their families and their community safe."

Higgins' lab tests samples for 15 different elements that can be used to develop a "fingerprint" of where lead is coming from, such as from the water main or within the house. PEI summer interns senior Elizabeth Stanley (left) and junior Hinako Kawabe (right) took the geochemistry course in spring 2017, where students learn to use tools such as a handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) reader. The instrument detects even minute levels of lead in a home's doors, windows and lower interior walls, as well as in soil around the foundation.

Between February and November 2017, Princeton students visited and tested 23 houses in Trenton, and analyzed around 750 water samples from 245 households, according to Higgins. (Water samples from each house include one cold- and one hot-water sample from the kitchen, and one sample from the bathroom.) The average lead content was 2.5 parts-per-billion (ppb) with 3.5 percent of the houses exceeding the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's standard of 15 ppb. The highest lead content encountered was 147 ppb, or nearly 10 times the EPA standard.

Kimberly Peterson, a junior in geosciences who is pursuing a certificate in environmental studies, said she was "compelled to take this class because it's a consistent, close-to-home project." Peterson has volunteered in Trenton as part of Princeton's Community Action. "It's a sad state of our society that it's the disadvantaged who are most impacted environmentally," she said. "This class is a cool amalgam of community service and the geoscience I've been studying for the past two years."

Junior Rebecca Mindel, an ecology and evolutionary biology major, said that her interest is in how science and public health overlap. She plans to write her senior thesis on the relationship between economic class and health issues.

"So far, I've been surprised by all the things we're capable of measuring, especially in a classroom setting," Mindel said. "Work like this gives us a place to start working on some of the disparities we see in education and public health."

The data the students get is unique in its small, extremely local scale, said Currie, the director of Princeton's Center for Health and Wellbeing, whose work on the effect of lead on child development prompted her to work with Higgins.

"One can see, for example, how potential lead exposure varies with distance from a particular source such as a highway, or with the state of a house and whether it has been subject to remediation efforts," Currie said. "This aspect highlights both the ubiquity of lead and how seemingly random it can be that one child is exposed and another is not."

Currie plans to couple the information from Trenton with U.S. Census data to examine the characteristics of communities at risk for lead exposure, she said. She also talks to students in the course about environmental justice, the higher exposure poor communities have to pollution, and how researchers can isolate pollution from other factors as a contributor to developmental and behavioral problems.

"John's data offer a powerful illustration about how widespread lead is in our older cities such as Trenton," Currie said. "The fact that there is still so much lead around, and the risk it still poses to children, should make people think, even if they don't live in Trenton. One thing that John also is doing is demonstrating how easy it is to test for lead."

The project aims to measure the level and source of lead contamination in Trenton homes, then eventually see how those data correlate with childhood health and development. Sophomore Young Joo Choi worked with the Trenton nonprofit organization Isles Inc. as a 2017 PEI summer intern to help test residents' homes for lead contamination. Students working in Trenton homes collect water samples as well as paint and soil samples from the residence's interior and exterior.

The methods his students use have been used by geoscientists for years, Higgins said. It was geochemist Clair Patterson of the California Institute of Technology whose work in the 1940s revealed the concentration of human-produced lead in the atmosphere and body.

"This work has deep roots in geoscience," Higgins said. "Geoscientists can take credit for being the first to figure out how widespread a problem lead was from an environmental perspective. The real overlap here is mostly analytical — the tests we apply in Trenton to look at lead in the water and lead in the paint are things geologists use in earth science."

Higgins was inspired to initiate the Trenton project by the Flint, Michigan, water crisis of 2014 when more than 100,000 people were exposed to high levels of lead due to poor drinking-water treatment. He realized that the problem partly came down to a lack of testing at the source. And he suspected that Trenton — an urban area with a history of heavy industry — would be at a high risk for lead contamination.

"More than anything, I was motivated by the recognition that the problems they had in Flint were from a measurement perspective, something that was easy for my lab to do," Higgins said. "It was an opportunity to bring cutting-edge chemical analyses to a local environmental problem and teach undergraduates in the process, a win-win for everyone involved."

Peter Rose, Isles' managing director of community enterprises and a collaborator on the project, said that the PEI project has allowed Isles to expand its lead-remediation efforts. For years, Isles has worked in Trenton to mitigate lead contamination in garden soil and household paint. At the time Higgins reached out, Isles was beginning to recruit community workers for New Jersey's Lead-Safe Home Remediation Pilot Program.

"PEI helped us connect our community health-worker training, public education and actual lead-hazard control work with a new element — water testing," Rose said. "This seemed like a perfect fit that blended a lot of our goals to protect Trenton residents from lead."

Because of the collaboration with Princeton and PEI, Isles has completed lead remediation at 57 housing units, more than twice as many units as other organizations in the pilot program, Rose said. Fourteen months ago, Isles set a goal of testing 1,000 Trenton homes for lead within two years. Half that goal is complete. He hopes to take the project with Princeton further by testing household objects such as toys and dishes, and by possibly forging a collaboration with the Isles Youth Institute in which students from Trenton can participate in laboratory work and chemistry lessons at the University.

"The connection to Trenton is important in the evolution of how Princeton sees the world and how the world sees Princeton," Rose said.

"PEI funding allowed us to deliver an education and testing service that is unique," he said. "I think the deeper value is to the Princeton students who get to apply their knowledge and education in a real-world situation. The things they are learning connects to the people whose lives that chemistry directly affects."

Junior Ellen Anshelevich, an anthropology major, and sophomore Polly Hochman, a geosciences major, took Higgins' course because it combines service and science.

"You can see directly how science can help people," Anshelevich said. "Coming into this class, I expected that lead would be higher where socioeconomic levels were lower, but what I found interesting is the relationship between blood levels of lead and behavior and educational performance."

"To see that lead contamination is consistent with that trend is troubling, but also interesting because you have to ask, if we clean up the lead in homes, what impact would that have on a child's life," Hochman said. "I've always loved science, but I wanted to find that connection between people and science and make something better."