From state-of-the-art theater lighting to microscopes that can visualize the delicate vascular system of a fruit fly, Princeton undergraduates are getting their hands on some of the most sophisticated equipment available today. Across the arts, natural and social sciences, humanities, and engineering, Princeton offers courses that provide self-directed exploration and experimentation using facilities that on other campuses are only available to graduate students or staff researchers.

The courses featured in this video series, usually taken during junior year, enable students to conduct independent research or creative work for their senior thesis, a months-long research project required for most students as a capstone to their Princeton experience.

A microscope’s eye on the fruit fly

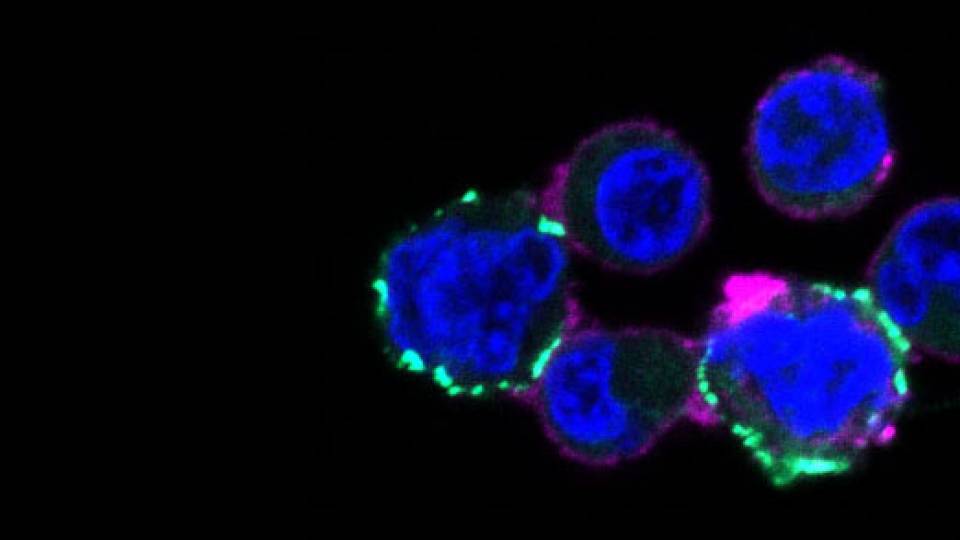

“Laboratory in Molecular Biology”(Link is external) (MOL 350) takes students from a research question to result and write-up in the course of a semester. Along the way, the students learn how to manipulate genes, place fluorescent tags on proteins and visualize outcomes using a high-powered imaging device known as a confocal microscope.

Students conduct original research projects using the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). The diminutive household pest offers a surprising variety of open questions that the undergraduates address working in pairs throughout the course.

Jodi Schottenfeld-Roames is the instructor of the course and a lecturer in molecular biology(Link is external). “The students are working at the same level of inquiry that others are doing at the postdoctoral and graduate student level,” Schottenfeld-Roames said.

In addition to teaching laboratory techniques, Schottenfeld-Roames hopes students come away from the class able to participate in public discussions about science. “The thing that I am really hoping for is that all of these students, regardless of whether they are going to go into science in the future, become science-literate citizens,” she said.

The confocal microscope is an essential tool in many biological studies because it yields 3-dimensional images rather than the typical 2-D views available from regular microscopes. It does this by capturing images of cross-sections through the object and using a computer to piece together the 3-D image.

“Being exposed to these experimental techniques early on helps us understand not just the steps that we are doing but really understand why we are doing these steps,” said Evelyn Wu, Class of 2019, who took the course in fall 2017.

Annie Choi, Class of 2019, paired with Wu to study how a certain gene affects fly development. Said Choi, “By looking at the confocal microscope, we actually know how the results would look like in an actual microscope rather than being given the example image in a textbook.”

Let there be (all-LED) light

Inside Princeton’s newly opened Lewis Arts complex, students explore the role of lighting in theatrical storytelling using some of the most sophisticated lighting systems available. The facility, which opened in fall 2017, features all-LED lighting instead of the more traditional incandescent systems.

“Several years ago, we were trying to decide whether or not we should go all LED,” said Jane Cox(Link is external), senior lecturer in theater(Link is external) in the Lewis Center for the Arts(Link is external) and director of the Program in Theater. “At the time, lighting technology wasn’t really ready, but we just decided that the University should be at the forefront of entertainment technology.”

The new lighting consoles enable students who are interested in both the arts and engineering to combine their passions and explore new directions in expression.

One of the courses that allows theater students to work with the lights is “Theatrical Design Studio”(Link is external) (THR 400 and VIS 400). The course embodies the “learn by doing” method that is an essential part of a theater education, Cox said.

“‘Theatrical Design Studio’ is a course that mentors students through designing a show for the theater program and working with a professional creative team,” Cox said. She said the process for lighting designers includes drafting the light plot, writing the light cues, and going through a creative process with the design team.

Abigail Jean-Baptiste, Class of 2018, is one of the students who has begun working with the new lighting equipment. Said Jean-Baptiste: “It’s exciting because it makes professionals want to work here. They want to see this new building and this new space with the best equipment that literally across the country has to offer. So it really makes the Princeton arts community stand out.”

Better living through chemistry

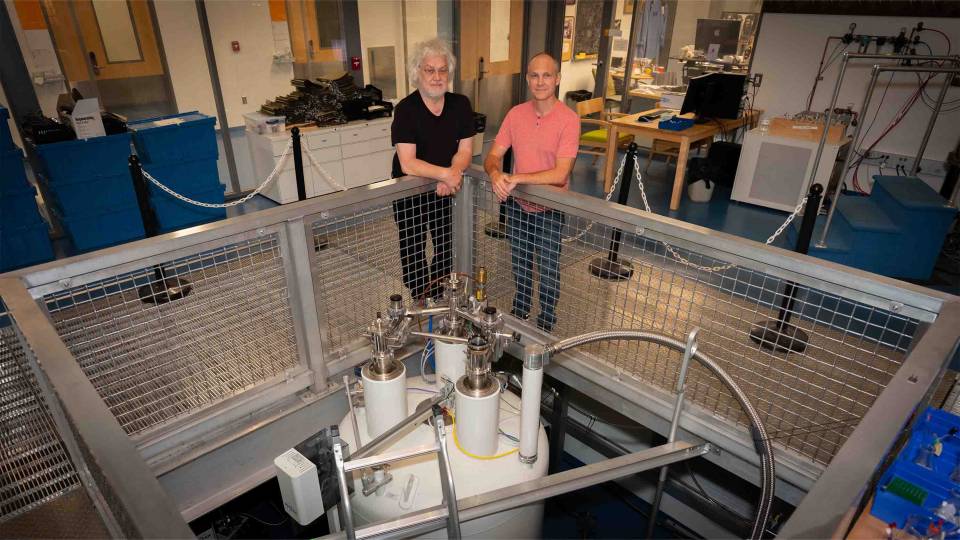

“Experimental Chemistry”(Link is external) (CHM 371) combines an introduction to instruments and advanced laboratory techniques with the challenges of taking on an original research project.

“The purpose of this laboratory course is to introduce students with modern techniques of experimental physical chemistry and inorganic chemistry,” said Chia-Ying Wang(Link is external), lecturer in chemistry(Link is external), who co-instructs the course with Michael Kelly(Link is external), also a lecturer in chemistry.

For the independent project, the students must discover and read background material, design experiments, and plan out the steps needed to reach conclusions. “This is important training because the setting is like when they work in a real research lab,” Wang said.

The students explore a wide range of methods for doing research in chemistry, including several types of spectroscopy in which light is used to probe the nature, identity and function of molecules. One type of spectroscopy the students learn to use is nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), which involves subjecting molecules to magnetic fields to reveal their structure.

In one independent research project, Class of 2018 undergraduates Phil Brooks, Zoe Tu and Teresa Tang built a visibile absorbance spectrometer, which can reveal information about molecules based on how they interact with light.

“The students really build these from scratch,” Wang said. “They really have this firsthand experience about how to build a homemade optical setup and that’s usually only an experience for graduate students.”

“It was a really independent project,” Brooks said, “putting all the components together, and then we had to code up the whole interface to run the machine using special laboratory software and learn about optics, learn about controls.

“If you’re actually doing state-of-the-art research, you really need to know how the machine is working,” Brooks said. “So this project gave all of us a really in-depth understanding of how an absorbance spectrometer works and what sort of things could go wrong with it and what its limitations are that you might not otherwise get.”

Tiny particles, big machines

Sometimes the largest instruments are needed to view the tiniest particles. Students in the course “Laboratory Techniques in Materials Science and Engineering”(Link is external) (MSE 302) are learning how to use large and sophisticated pieces of equipment to probe materials that are several times smaller than the width of a human hair.

The instruments are part of Princeton’s Imaging and Analysis Center(Link is external), which is part of the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials(Link is external) (PRISM). The facility is located in the basement of the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment(Link is external) where the equipment is insulated from vibrations from traffic and other disturbances. Several of these instruments are the latest and most sophisticated versions the field has to offer.

“The students are learning theory behind materials science characterization techniques as well as gaining hands-on practical experience on how to utilize these techniques,” said Rodney Priestley, associate professor of chemical and biological engineering and one of three instructors for the course, which is administered by PRISM.

Two techniques the students are learning are transmission electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Both involve using beams of electrons to probe the structure of a material.

Grace Kresge, Class of 2019, is a junior studying chemical and biological engineering who took the course this fall. One of the projects involved scanning electron microscopy images of a morpho butterfly wing, which gets its beautiful blue color not from pigments but from how light interacts with its physical structure.

“It is really exciting to work with the state-of-the-art equipment,” said Kresge, who plans to go to graduate school for chemical engineering focused on materials science.

“This course is going to prepare me — it is already preparing me — for graduate-level characterization work,” she said. The techniques are “things that I have seen … graduate students in the past do. I know that this is getting me on track to be a competitive candidate to go to graduate school.”