Princeton researchers have found that smartphone data can be used to track users even when the phone’s GPS is off.

Demonstrating a potential privacy breach, a team of Princeton University engineers has developed an app that can locate and track people through their smartphones even when access to the Global Positioning System, or GPS, data on their devices is turned off.

The app, called PinMe, mines information already stored on smartphones that — unlike GPS — doesn’t require permission for access. When computed along with publicly available maps and weather reports, this data can help identify if a person is traveling by foot, car, train or airplane, and chart their route of travel.

The research team reported on its patent-pending technology in a Sept. 15 paper(Link is external) in the journal IEEE Transactions on Multi-Scale Computing Systems.

The app, they wrote, uses a series of algorithms that locate and track someone by processing information such as a phone’s IP address and time zone, along with data from its sensors. Among other information, phone sensors collect compass details from a gyroscope, air pressure readings from a barometer, and accelerometer data. All the while, the presence of the app can be virtually undetectable.

“PinMe demonstrates how information from seemingly innocuous sensors can be exploited using machine-learning techniques to infer sensitive details about our lives,” said Prateek Mittal(Link is external), assistant professor in Princeton’s Department of Electrical Engineering(Link is external) and PinMe paper co-author.

Prateek Mittal, assistant professor of electrical engineering, worked with colleagues to develop the PinMe app, which mines information already stored on a smartphone that — unlike GPS — doesn’t require permission for access.

The accuracy of PinMe has significant implications in an era of heightened tensions about the security and privacy cracks forming in our increasingly digitized lives. PinMe creators hope that exposing the sensor security flaw will influence the next generation of smartphone operating systems to include an “off” switch for sensor data, some of which is collected for fitness and interactive game apps that track people’s movements.

“We wanted to raise public concern about this issue,” said Arsalan Mosenia, a postdoctoral research associate in electrical engineering and a member of the PinMe team.

Despite the worrying findings, the consequences of PinMe are not all sinister, the developers say. The technology is a strong alternative to GPS-based navigation in autonomous cars and other forms of transportation, since GPS signals are susceptible to fraud.

“[Attackers] can convince a ship or car that they’re in a location that they’re not actually in,” which could be problematic for American ships navigating international waters, for instance, or for the safety of the passengers of autonomous cars, points out Niraj Jha(Link is external), professor of electrical engineering at Princeton and paper co-author. The PinMe team is already talking with technology companies about licensing the app as a navigational tool.

Mosenia developed the app last year as a Princeton Ph.D. student, in collaboration with Mittal, Jha and Xiaoliang Dai, a Princeton electrical engineering Ph.D. student.

The team sought to push the limits of past research on phone security, Mosenia said. Other scientists have used sensor data to locate people by measuring the power consumption of phones while they travel through known streets or through reading the accelerometer.

But their apps could only handle one mode of travel, usually driving, and needed advance information about the phone owner, such as initial location or the area where the person was traveling. Some apps also collected data so frequently, up to 40 hertz, or 40 times per second, that they were bound to raise the suspicion of security apps.

What makes PinMe so powerful, and thus undetectable, is that it needs only to collect a dribble of data: five times per second on average (for driving, the rate is even lower: once every 10 seconds). It also can track a person through multiple modes of travel, and doesn’t need advance information.

“We wanted to assume nothing about the user,” Mosenia said.

From left: Niraj Jha, professor of electrical engineering, and Arsalan Mosenia, a postdoctoral research associate, are part of the PinMe team.

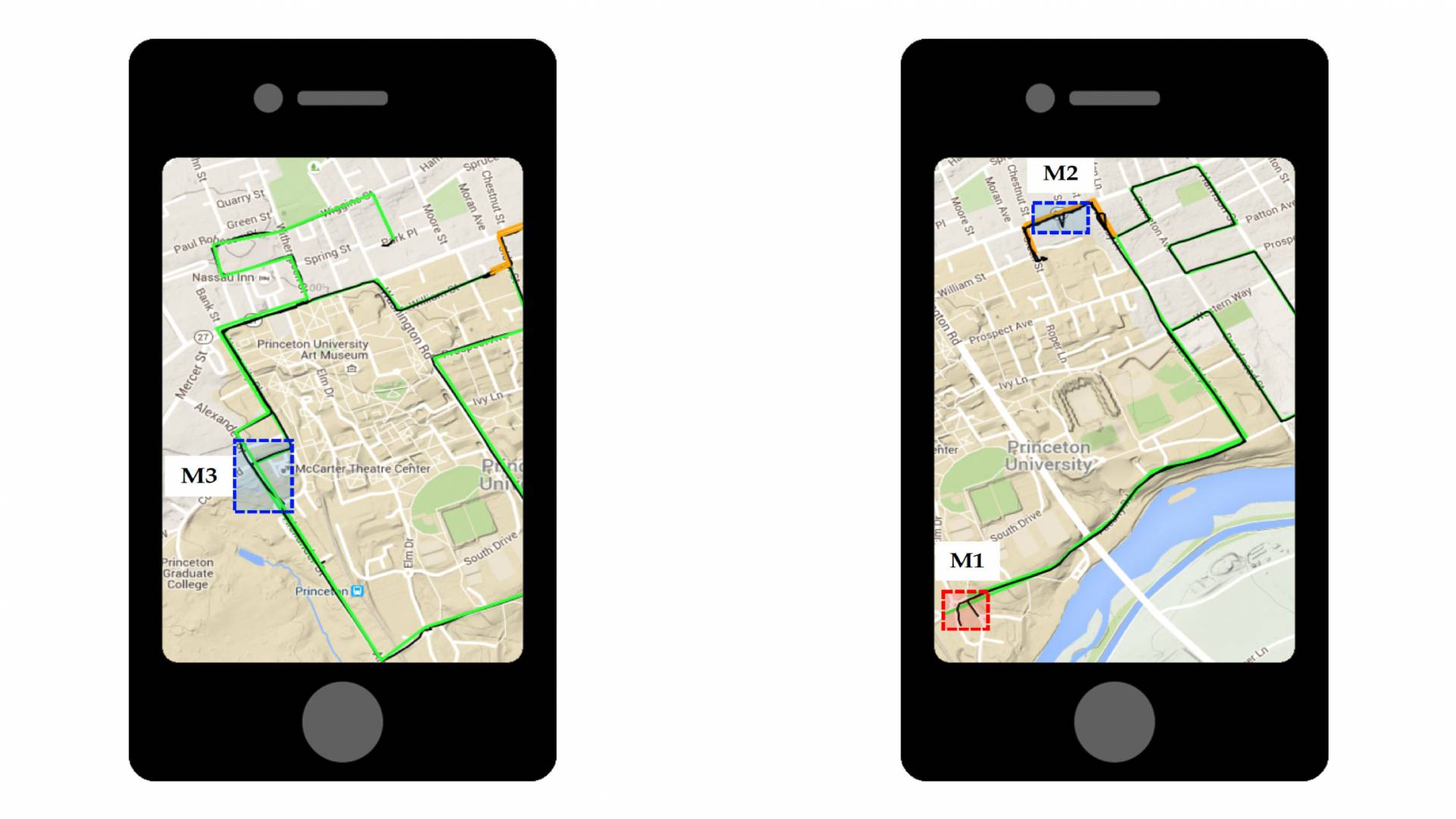

To run their experiment, the Princeton researchers collected phone data from three people for one day after installing PinMe on their phones — Galaxy S4 i9500, iPhone 6 and iPhone 6S — running either Android or iOS. The study subjects traveled by foot, car, train and airplane through cities including Philadelphia, Dallas and Princeton.

PinMe first read each phone’s latest IP address and network status to nail down its last Wi-Fi connection. This narrowed down the search by exposing the phone’s most recent location.

Next, to determine the mode of travel, the app used a machine-learning algorithm that had been trained to recognize the difference between walking, driving, train-riding and flying. It did this by gathering clues from a phone’s sensors that exposed crucial information: how fast the person was moving and the direction of travel, how often the person was stopping and then moving again, and the person’s altitude.

Once the person’s activity was revealed, PinMe launched one of four additional algorithms targeted for each mode of transportation. These calculations mapped the route the person was traveling by matching phone data against public information. Navigational maps available from open-source software OpenStreetMap, for instance, helped PinMe map a phone’s specific routes of travel, while elevation maps from Google and the U.S. Geological Survey offered altitude details for every point on Earth.

The app also used detailed temperature, humidity and air pressure reports from The Weather Channel’s many weather stations to contextualize a phone’s air-pressure-sensor readings, since these are influenced by weather conditions and elevation. Train and plane flight schedules also offered clues.

When a test subject flew from Philadelphia to Dallas, for example, the app recognized spikes in elevation and acceleration. This implied that the person was on a plane that was taking off or landing. The time lapse between the spikes revealed flight duration. Then, evidence including time-zone data, in combination with weather and airport elevation levels, plus flight timetables, were matched up to correctly identify takeoff and landing airports.

While PinMe is extremely accurate for many modes of travel, it isn’t perfect. A software like Tor, which can be installed to hide IP addresses from trackers, would make a phone hard, though not impossible, to pinpoint. PinMe could also falter by mining bad public records, or by following someone through a city, such as Manhattan, with no elevation changes and similar-looking roads packed into a grid.

In the future, people might be able to turn off their sensors. But for now, short of turning off the phone, there’s little hope of hiding from PinMe, which is a major concern for data security experts like Supriyo Chakraborty, a researcher at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center.

“The [PinMe] attack is ... extremely potent,” said Chakraborty, who was not involved with the research.

PinMe’s developers already are working on ways for people to defend themselves against it, said Jha, whose research focus is on the security of the “internet of things,” a phrase that describes the increasingly digital products that power our daily activities.

“I think a lot of follow-up should deal with how to prevent this attack,” he said.