Nabil Shaikh's senior thesis took him more than 8,000 miles from Princeton to Hyderabad, India, where he interviewed terminally ill cancer patients about their experience with end-of-life care.

For Shaikh, a politics major from Reading, Pennsylvania, the fieldwork was just one part of a four-year journey through the University that gave him the academic grounding, intellectual support and real-world experience needed to explore ethical, political and practical questions about caring for the terminally ill.

Shaikh came to the University expecting to major in chemistry and take a traditional route to medical school. After his first year at Princeton, he spent a summer working in Budapest, Hungary, through the International Internship Program, which piqued his interest in health care access for disadvantaged populations. An internship after his sophomore year at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston through the Princeton Internships in Community Service program drew him to a range of questions surrounding end-of-life care.

"At the individual level, I wonder about the ideal and most well-imagined form of living out the best of your days at the end of your life," Shaikh said. "At the caregiving level, there's the question of how you turn from figuring out the best curative route for a patient to focusing on improving quality of life. And at the policymaking and political level, how can we talk about end-of-life care as just as important an aspect of the public health agenda as issues such as fighting infectious diseases?"

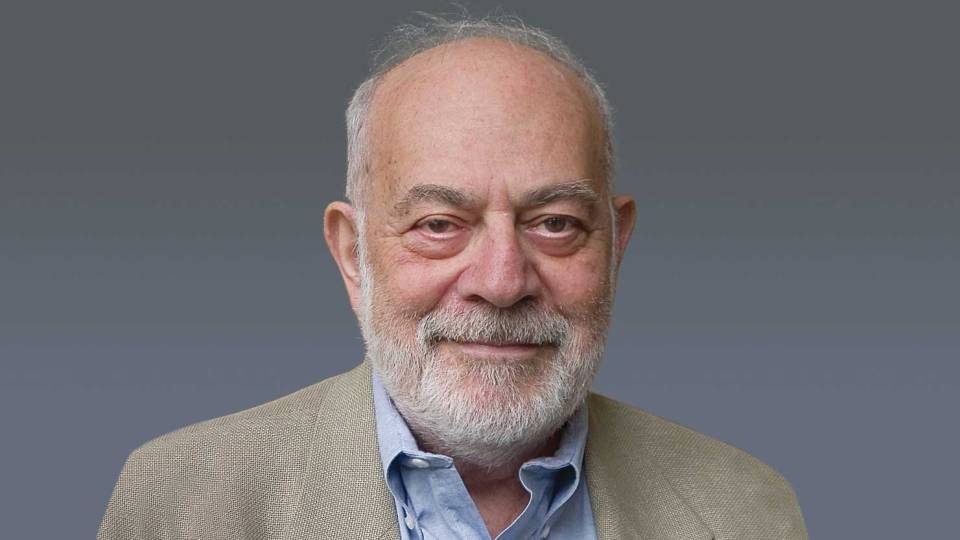

Nabil Shaikh (left) discusses his senior thesis project with his thesis adviser, Melissa Lane, the Class of 1943 Professor of Politics. Shaikh's thesis explores ethical, political and practical questions about caring for the terminally ill. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

The senior thesis, considered the capstone of Princeton students' academic journey, is an independent work that requires seniors to pursue original research and scholarship under the guidance of faculty advisers.

Shaikh also turned to academic opportunities available through the Department of Politics and two programs where he is pursuing certificates, the Program in Global Health and Health Policy and the University Center for Human Values (UCHV).

"Nabil has approached difficult ethical and political questions about end-of-life care with deep sensitivity," said Melissa Lane, the Class of 1943 Professor of Politics, director of UCHV and Shaikh's thesis adviser. "He has explored these issues both in practice … and in theory, drawing on philosophical debates about dignity and global health scholarship about equity, doing all this with a contagious mixture of energy and humility."

The University's influence has also extended beyond the classroom, and Shaikh cited in particular the importance of his experiences as part of Religious Life Council (RLC), the Muslim Students' Association (MSA) and the Pace Council for Civic Values.

"I think my thesis process and my intellectual experience with my independent work and internships have been shaped by the pushes I've received from my friends on the RLC and MSA to think deeply about systemic issues, philosophical quandaries, and moral and ethical dilemmas," he said.

Shaikh received support through the Global Health Scholarship from the Center for Health and Wellbeing to travel for eight weeks during the summer of 2016 to Hyderabad, a city of more than 7 million people in southern India. He was drawn to the city in part because it has large Muslim and Hindu communities with diverse notions of death and dying, and because little research has been done on the health system there, which includes basic care provided by the government at no charge and specialty hospitals for those who can afford it.

He interviewed 80 patients who were terminally ill with cancer. Half were receiving palliative care — care focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of their illness — while the other half were not. Palliative care is rare in Hyderabad, where most cancer patients are diagnosed late in the course of their illness and don't have access to appropriate pain relief or other supportive care. In Hyderabad, there are about 40,000 cancer cases a year and only about 20 hospice beds, Shaikh said.

His thesis includes information collected from his interviews, a theoretical portion that explores expanding the definition of health care to include noncurative care, an empirical portion that includes comparing end-of-life care available in different countries, and a section in which Shaikh proposes his own ideas for why end-of-life care should be part of the broader global health agenda.

"What we have right now in the U.S. and in the developing world is a situation where we really value curative treatment and medical treatment that extends one's life," he said. "We don't often think about other aspects of health care that are important, such as preserving human dignity and adding quality of life."

Shaikh plans to continue to examine questions about end-of-life care through the Scholars in the Nation's Service Initiative (SINSI) of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. As part of the program, Shaikh will earn a Master in Public Affairs and complete a two-year fellowship in the federal government. Following SINSI, Shaikh hopes to explore a career in public health and policymaking.

"I came to Princeton as someone who was very interested in medicine and caregiving and gradually moved toward an even more pronounced interest in health policy and public health," Shaikh said. "I was happy to have these chances to explore these topics and realize that I wanted to do something in both policy and medicine."