With two suns in its sky, the planet Tatooine, home of Luke Skywalker, hero of the “Star Wars” films, is portrayed as an immense and parched desert. In real life, scientists know from observatories such as NASA’s Kepler space telescope that two-star systems can support planets, but planets thus far discovered in double-star systems are large and gaseous. So the question remained: If an Earth-size terrestrial planet were orbiting two suns, could it support life?

A study in the journal(Link is external) (Link opens in new window) Nature Communications has now found that an Earth-like planet orbiting two stars could be habitable if it were within a certain range from its two stars — and it wouldn’t necessarily be the desert of Skywalker’s native world. Instead, a planet covered in water could retain its water for a long time, the researchers report.

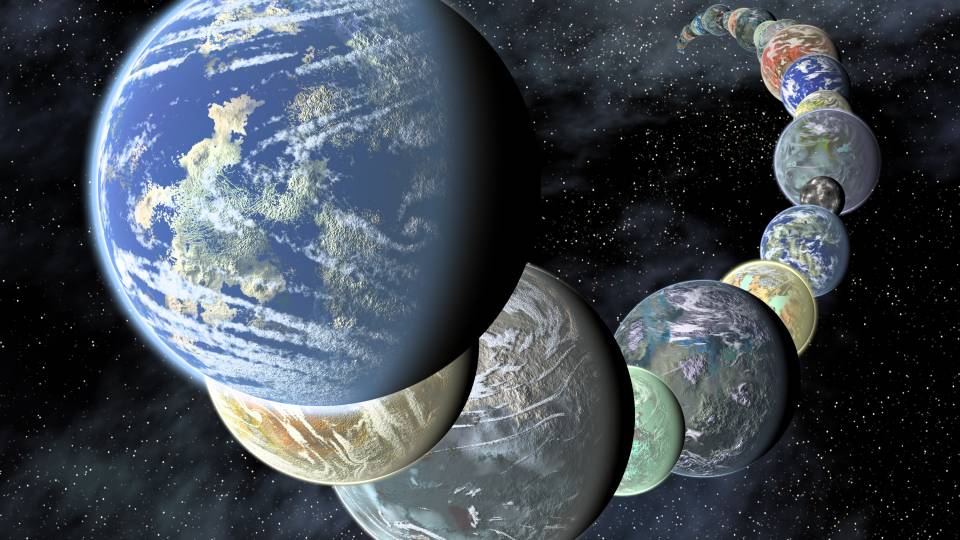

A study in the journal Nature Communications has found that an Earth-like planet orbiting two stars could be habitable if it were located within a certain range, or “habitable zone,” from its two stars. The researchers created climate models for a hypothetical planet in the two-star system Kepler-35, as depicted above. On the far edge of the habitable zone, the water-covered planet would have a lot of variation in its surface temperatures, but closer to the stars the global average surface temperatures would stay almost constant. (Image courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

“Double-star systems of the type studied here are excellent candidates to host habitable planets, despite the large variations in the amount of starlight hypothetical planets in such a system would receive,” said first author Max Popp, an associate research scholar in Princeton University’s Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences(Link is external) and at the Max Planck Institute of Meteorology in Germany.

Popp and Siegfried Eggl, a California Institute of Technology postdoctoral scholar at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory created a model for a planet in the binary, or two-star, system Kepler-35. The stellar pair Kepler-35A and 35B host a planet called Kepler-35b, a giant planet about eight times the size of Earth with an orbit of 131.5 Earth days. Popp and Eggl discounted the gravitational influence of this planet and added a hypothetical water-covered, Earth-size planet around the Kepler-35 stars. They examined how this planet’s climate would behave as it orbited the stars for periods between 341 and 380 days.

“Our research is motivated by the fact that searching for potentially habitable planets requires a lot of effort, so it is good to know in advance where to look,” Eggl said. “We show that it’s worth targeting double-star systems.”

In exoplanet research, the “habitable zone” denotes the area around a star wherein a terrestrial planet like Earth would most likely have liquid water on its surface. In the case of binary systems, because two stars are orbiting each other, the habitable zone depends on the distance the planet is from the center of mass around which both stars orbit. To make things even more complicated, a planet orbiting two stars would not travel in a circle; instead, its orbit would wobble through the gravitational interaction of the two stars.

Popp and Eggl found that on the far edge of the Kepler-35 habitable zone, their hypothetical planet would be cold and experience a lot of variation in its surface temperature. Because the cold planet would have a small amount of atmospheric water vapor, global average surface temperatures would fluctuate by as much as 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) in the course of a single year. For reference, climate change on Earth is expected to become catastrophic if the global average temperature rises 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, or where it was more than 200 years ago.

“This is analogous to how, on Earth, in arid climates such as deserts, we experience huge temperature variations from day to night,” Eggl said. “The amount of water in the air makes a big difference.”

Closer to the stars, however, near the inner edge of the habitable zone, the global average surface temperature on the same planet would stay almost constant. That is because more water vapor would be able to persist in the atmosphere to act as a buffer that keeps surface conditions stable.

As with single-star systems, a planet beyond the outer edge of habitable zone of Kepler-35′s two suns would eventually end up in a “snowball” state completely covered with ice. If it is closer than the inner edge of the habitable zone, the atmosphere would insulate the planet too much and create a runaway greenhouse effect that could turn the planet into a Venus-like world inhospitable to life, the researchers found.

The researcher’s climate model also found that, compared to Earth, a water-covered planet around two stars would have less cloud coverage. That would mean clear skies and striking double sunsets that, perhaps with less sand, are akin to the iconic scene of Skywalker gazing upon the barren landscape of Tatooine as one sun rises and another sets.

The paper, “Climate variations on Earth-like circumbinary planets,” was published April 6 in Nature Communications. The paper was supported by the FWF Austrian Science Fund (project S11608-N16), the IMCCE Observatoire de Paris and the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Morgan Kelly, Princeton University Office of Communications, and Elizabeth Landau, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, contributed to this article.