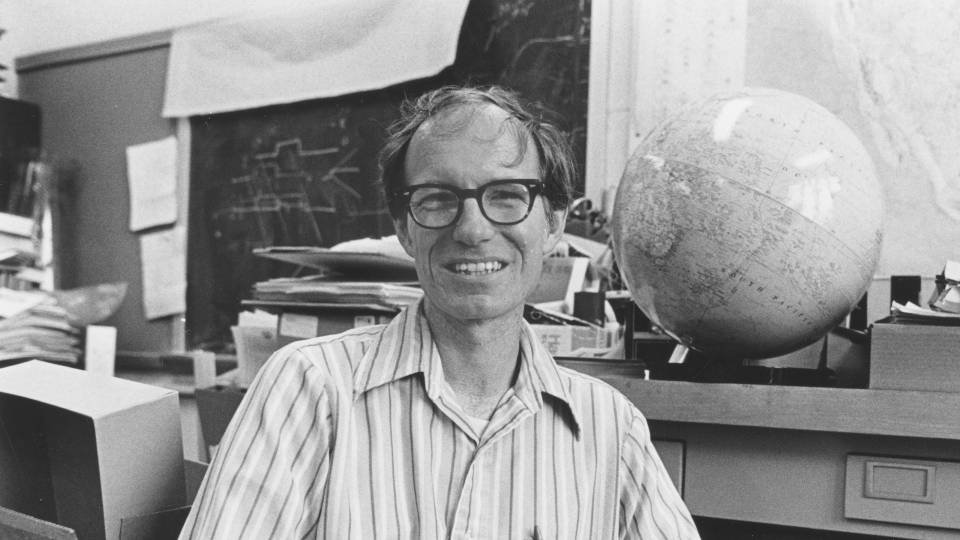

William "Bill" Bonini, whose more than 40 years as a Princeton University professor were distinguished by his dedication to students and alumni, as well as his affable relationships with colleagues, died Dec. 13, 2016, with his family by his side. He was 90.

Bonini, the George J. Magee Professor of Geophysics and Geological Engineering, Emeritus, and professor of geosciences and civil engineering, emeritus, first came to Princeton as a student. In 1945, while a student at the University, he was drafted into the U.S. Navy during the final months of World War II. He returned to Princeton as a member of the Reserves and earned his bachelor's and master's degrees in geological engineering in 1948 and 1949, respectively.

Bonini joined Princeton's faculty in 1952 as an assistant professor in the former Department of Geological Engineering. His distinguished work in magnetic and gravitational geophysics spanned the departments of geophysics and geological engineering and civil engineering. He formally joined the Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences — now the Department of Geosciences — in 1970 before transferring to emeritus status in 1996.

Regarding his retirement, Bonini told The Daily Princetonian in 1996: "I will miss the students most of all. It is very refreshing to talk to 18- and 19-year-olds every day." The article noted that he had advised more than 300 students, yet he most enjoyed teaching introductory courses because "he can see in his students a rapid acquisition of knowledge."

Among his many achievements at Princeton, Bonini received the President's Award for Distinguished Teaching in 1992, and the Princeton Award for Excellence in Alumni Education in 2010. He was director of undergraduate studies for the Department of Geology and Geophysics from 1973 to 1994, and chair of the Geological Engineering program from 1973 until his retirement. He also was director of the Princeton Summer Field Course program at the Yellowstone-Bighorn Research Association in Red Lodge, Montana, for more than 30 years.

Bonini had been at Princeton for 16 years when Lincoln Hollister, now professor of geosciences, emeritus, arrived at Princeton in 1968. Hollister, like many colleagues and students, was drawn to Bonini's friendly composure and readiness to engage in long, illuminating discussions, he said.

"He was a gentleman with a capital G," said Hollister, who often visited Bonini after the two had retired and last saw his friend in the spring. "There were always students lined up at his door. He wasn't impatient for the next student to come in, or hurrying up to get out of there. He gave people his attention and his time, as much as they needed."

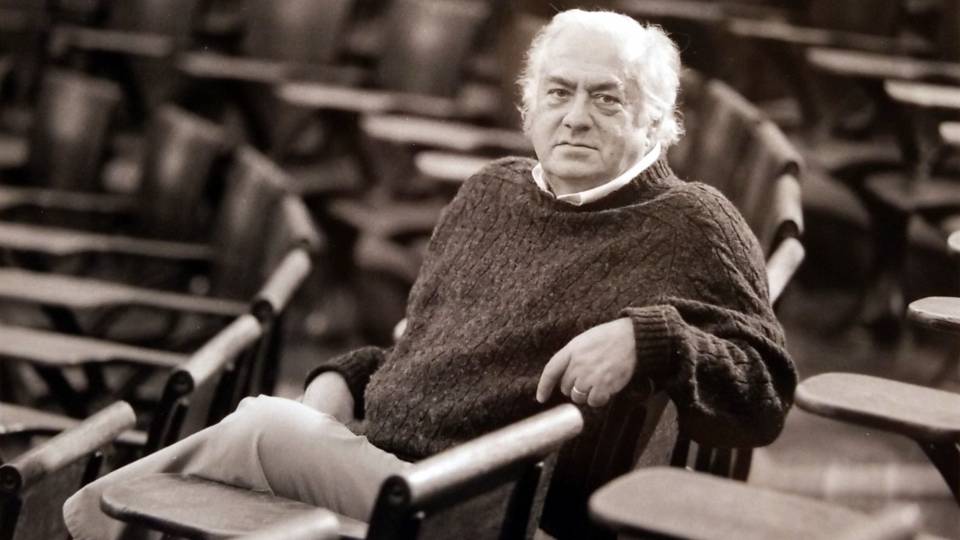

For years, Hollister would have lunch nearly every day in Bonini's office with a regular group of people that included writer John McPhee, Princeton's Ferris Professor of Journalism. "John McPhee had lunch with him — I think that tells you enough right there about how smart Bill was," Hollister said, laughing. "Unlike most of us, [Bill] had a clean office and a clean table, and we could stroll in and have lunch. There were three or four of us who had lunch together every day and talked about everything under the sun."

Hollister admired how hard Bonini worked to enhance the undergraduate experience by introducing and redesigning courses, and working with University committees to improve access to education. Above all else, Bonini committed long hours to help students refine their ideas and research.

"He inspired the rest of us and very much was a role model that way. He made the department better because of his ability to teach and interact with the students," Hollister said. "The values that are promoted as being Princeton, he was."

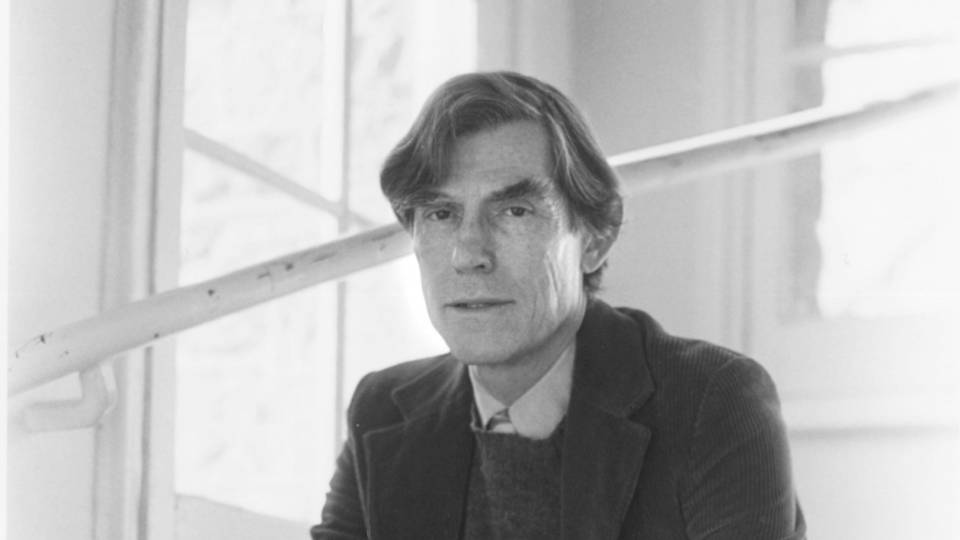

"When people think about Bill, of course they remember him as a well-known scientist, but the thing I think about is what a devoted and remarkable teacher he was," said Rick Vierbuchen, who, with Bonini as one of his advisers, received his Ph.D. in geology and applied geophysics from Princeton in 1979.

"Bill was the sort of professor that people want to stay in touch with. You go back and visit him, talk to him about your career, you want him to meet your children," said Vierbuchen, who had spoken with or visited Bonini every year since leaving Princeton. "Anyone who spent time with him thought of him as a good friend."

Vierbuchen met Bonini in 1973 when he applied to be a field assistant for a regional gravity survey Bonini was undertaking in Venezuela. That trip eventually led Vierbuchen to his own work on the geology and tectonics of Venezuela. At the start of Vierbuchen's first field season, Bonini went to Venezuela with him to help find a field assistant, secure housing and even obtain a supply of anti-venom for snakebites, among numerous other logistical challenges.

"Bill wouldn't leave until he knew I was set up — I was always really grateful for that," Vierbuchen said. "He would always say, 'My goal with you and all my students is to make you a better scientist than I've been.' Bill was such a darn good scientist that it was very difficult to be better than him."

Vierbuchen said Bonini encouraged students to take risks and explore new techniques or challenging disciplines. If Bonini's opinion turned out to be wrong, he cheerfully admitted it.

"He always wanted to get the right answer, even if it wasn't his answer, which is a great example to set for students," Vierbuchen said. "The skills that Bill taught were themselves quite useful, but the flexibility, the broad interest in subjects, the excitement of learning new things and the lack of personal identification with a given solution, all those things were also important.

"He's a role model you think of when you're in a difficult situation," he said. "When there was a problem, Bill did not ignore it or run away from it — he found a positive way to deal with it."

Current and former students were a frequent presence at Bonini's household, said his youngest daughter, Jennifer Bonini, of Princeton's Class of 1991. All four of Bonini's children graduated from Princeton.

"On numerous occasions he would invite students over to the house for special dinners and engaging dinner conversations — the house was always open for students who were stranded for the holidays and we often made room on Thanksgiving for stray students," she said. "He had a positive, outgoing personality with a sharp intellect and everyone was a friend. Anyone who needed a place to stay was welcome at our home."

Her father attributed his love of teaching and the outdoors to his years as a Boy Scout — he eventually became an Eagle Scout — Jennifer said. He exhibited with his children the same patience and dedication to teaching he showed his students at Princeton, she said.

"Dad was a great role model and parent, and had a huge heart," Jennifer said. "As a father, he was very supportive of hands-on learning opportunities, whether it was working with us in the kitchen, allowing my brothers the opportunity to rebuild engines in the garage, doing repairs around the house, or helping us work through our school work. He saw projects as an opportunity, and was a happy collaborator to young minds willing to learn new skills. He never let the demands of a hectic work life interfere with the chance to be accessible to his children."

Bonini was born in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 23, 1926, and was the first person in his family to complete college. Bonini received his Ph.D. in geology and geophysics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1957. It was in Madison that he met his wife, Rose, whom he married in 1954.

Bonini is survived by his wife, Rose Rozich Bonini; his son, Jack Bonini of the Class of 1979 (Loretta Estabrooks) of Holmes Beach, Florida; daughter Nancy Bonini of the Class of 1981 (Anthony Cashmore) of Penn Valley, Pennsylvania; son Jamie Bonini of the Class of 1985 (Patricia) of Cincinnati; daughter Jennifer Bonini of Princeton's Class of 1991 (Scott Miller) of Laramie, Wyoming; and seven grandchildren. He was preceded in death by sisters June and Doris.

A memorial service will be held at a later date. In lieu of flowers, memorial donations can be made to the Yellowstone-Bighorn Research Association Field Camp.