More than two years after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the fraught relationship between law enforcement and African Americans continues to spark controversy and calls for action.

This tension — and how to address the divide between communities and the police — were examined at a policy forum held Friday, Dec. 9, at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs(Link is external).

The daylong forum, “From Ferguson to Dallas to Charlotte: Racial Justice and Policing in America(Link is external),” convened research scholars, former and current senior law enforcement officials, activists, policymakers, students, and community members to examine how law enforcement and communities can better work together to ensure residents’ safety and well-being. A recording of the forum is available on the Woodrow Wilson School’s YouTube channel(Link is external). Highlights of the discussion on social media are captured in this Storify(Link is external).

(From left to right) Ronald Davis of the U.S. Department of Justice and Asa Craig, a master in public policy student, participate in a panel on community relations during the conference “From Ferguson to Dallas to Charlotte: Racial Justice and Policing in America” on Friday, Dec. 9, at the Woodrow Wilson School. (Photos by Egan Jimenez, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs)

Keynote addresses and panel discussions focused on community relations and accountability between the police and residents; the role of activism in creating change; issues of racial justice, profiling and human rights; as well as the role of policy going forward.

In his opening remarks, Benjamin Jealous, former president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and visiting lecturer in public and international affairs at the Wilson School and John L. Weinberg Visiting Professor, set the tone of the day’s discussion.

“We have to come together across old lines,” Jealous said. “We have to find a way that we all have an interest in making sure there’s a functional relationship between the police and the communities most in need in our country.”

In her keynote address, Kathleen O’Toole, chief of the Seattle Police Department, reiterated the challenging relationship between race and policing.

“There has never been a more difficult time in America,” O’Toole said, “but with that comes an opportunity, and it’s important that we engage in these discussions and learn from and listen to one another. We, as leaders, need to bring a sense of urgency for reform.”

While the panels and keynote addresses were wide-ranging, several themes emerged. Speakers particularly focused on police training and reform, strengthening community relations, using activism to enact change and the role of policy today and in the future.

In his opening remarks, Benjamin Jealous, former president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and visiting lecturer in public and international affairs at the Wilson School and John L. Weinberg Visiting Professor, introduced the issues and set the tone for the day’s discussion about race and policing.

A call for reform

Addressing social injustices requires an introspective look at history, and this begins with the criminalization of African Americans in America, panelists argued during a morning session on activism and the role of protests.

“You can’t talk about policing without discussing racial oppression,” said Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor(Link is external), assistant professor in Princeton’s Department of African American Studies(Link is external).

While a discussion is a start — and having a seat at the table is important — it may not be enough to make an impact, panelists said.

“Having a seat at the table is symbolic but it doesn’t produce a change,” said senior Assani York. “That said, the table was built on the backs of black people. … We need a new table.”

When discussing real change, York and senior Destiny Crockett, both members of the Black Justice League, a group started by Princeton students in response to the Ferguson shooting, introduced the concept of a world without police. In this scenario, community members would police each other without the use of force.

“I wonder what real change would look like if we just didn’t assume it was criminal to start with, if all solutions to social change didn’t involve police,” Crockett said. “What is a world like without police? Could communities police each other without police?”

But removing the immediate criminalization of some people, especially African Americans, could be hard to imagine, panelists offered. This is mostly because there are few moments in history to show us otherwise.

“Even in the short run, we have criminalized spaces of color more than ever before,” said Professor Heather Ann Thompson from the University of Michigan. “We don’t know another world. We are still talking about this as if the primary reason why we have prisons is crime management, but today’s crime rate is lower than it’s ever been. When you have social problems, you deal with them in another social justice network. Not criminalization.”

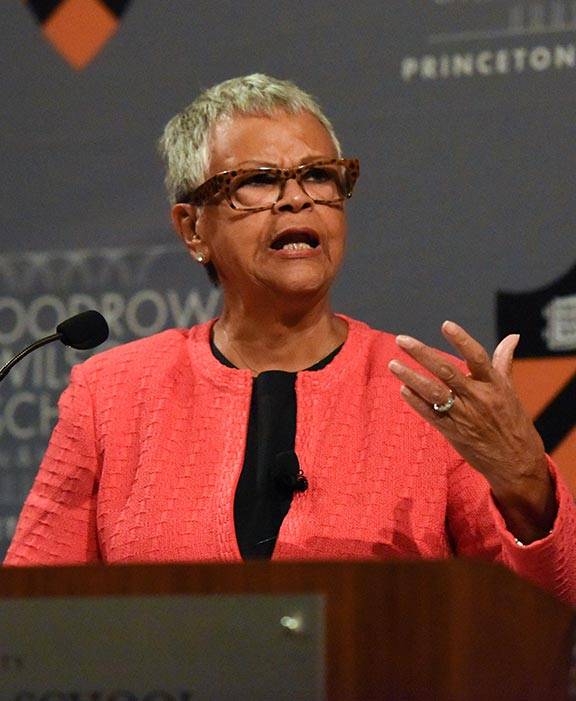

These are some of the reasons why now may be the best time for radical change, urged Charlene Caruthers in an afternoon keynote address. Caruthers is the national director of the Black Youth Project 100, an organization dedicated to creating justice and freedom for all black people.

“Abolishing the police is not about living in a world without violence. We can live in a world where when harm happens we just deal with it in radically different ways,” Caruthers said. “Our problem is fundamentally about the fabric of America and how it operates. Now is the time for us to be radical in our thought because the possibilities are endless.”

In one of the final keynote addresses, Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, D-N.J., outlined specific policies to address the fraught relationship between the community and law enforcement.

The rearview mirror

Speakers throughout the day reflected on the concept of looking backward to move ahead. This theme was especially present in the discussions focused on policy, reform and change.

“We need to understand what’s behind us to safely move forward as a profession,” Ramsey said. “We need to have the right policies in place but also transparency and accountability.”

Abigail Gellman, a Princeton senior studying these issues, noted that many accountability discussions have focused on the tensions between individuals and systems.

“You can’t just look at one or the other. When thinking about police reforms, you have to ask yourself: Is the policy giving more money to policing or reducing the extent of policing?” Gellman said.

To frame the discussion about accountability, Kimberly Anderson, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina, walked the audience through the recent shooting in Charlotte, North Carolina. The panelists then shared ideas for increasing transparency. These included hiring outside organizations to investigate police shootings, implementing drone usage for survelliance and leveraging social media as a communication tool. The role of unions and the hiring process must also be examined, panelists said.

“We see police officers resign, and then they are hired in another department,” said Professor Kimberly Jade Norwood of Washington University in St. Louis. “We have to deal with this. Even in cases where the officer was fired, this doesn’t seem to have an impact on a rehire in another community. We have to get into decertification.”

Another issue lies within the failure to indict police officers who have been accused of serious crimes like manslaughter, said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum. This stems back to a 1989 Supreme Court case — Graham v. Connor — which determined that an “objective reasonableness standard” should apply to civilian’s claims regarding excessive force by police officers. Essentially, this meant that if a police officer felt his or her life was in danger, this should be taken into account in court.

“This case was a landmark decision. And it’s still significant now,” Wexler said. “What they saw was that police officers have to make split-second decisions, but these decisions aren’t viewed in terms of what could’ve been done. Instead, they are decisions under changing circumstances or what an ‘objectively reasonable person’ would do. That’s the standard that’s held true for all of these years. It becomes significant. When you look at why they don’t indict police officers, the prosecutor points at that decision.”

Panel members (from left) Benjamin Jealous; Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, assistant professor of African American studies; senior Destiny Crockett, senior Asanni York; and Heather Ann Thompson of the University of Michigan discuss “The Role of Activism in Effecting Change” during the conference.

The day’s discussions ended with a look toward the future with two keynote addresses by Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, D-N.J., and Paul Fishman, a 1978 graduate of Princeton and U.S. attorney for the District of New Jersey.

Coleman detailed policies enacted by Congress aimed at addressing a number of policing practices. A number of these focus on the use of force, de-escalation training, investigations and data collection as well alternatives to arrests and mandated criminal investigations.

In 2015, Congress passed an act concerning the excessive use of force. Now, a bill is under consideration in Congress that would ban police officers from using force against the throat or windpipe.

Another bill that’s been introduced to the House is the Police Accountability Act, which holds that any police officer who is accused of murder or manslaughter in the line of duty be prosecuted on the federal level.

These proposed policies are a start, but they are only one part of the solution, Coleman said.

“We need a community swell,” she said. “We are harkening back to a period of activism that is so vitally important. We need to take a very serious look at how we protect those who are most vulnerable among us. …We have a lot of work to do in the next couple of years.”

In addition to Princeton University, the forum speakers hailed from the ACLU, ACLU of North Carolina, Black Youth Project 100, Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Police Executive Research Forum, Seattle’s Police Department, Stone Hill Church of Princeton, University of Michigan, U.S. Attorney for the District of N.J., U.S. Department of Justice and Washington University in St. Louis.

The event was co-sponsored by the Wilson School and Princeton University’s Women*s Center(Link is external), the Carl A. Fields Center for Equality and Cultural Understanding(Link is external), the Office of the Vice President for Campus Life, the Department of Public Safety, and the LGBT Center(Link is external).