When Nancy Weiss Malkiel, professor of history, emeritus, and former dean of the college at Princeton University, was asked by then President Shirley M. Tilghman if she would write a book about coeducation at Princeton, she willingly obliged. After all, she had been teaching in the Department of History since 1969 and had firsthand knowledge of the process of coeducation and its progression.

But, as she dug deep into the history of Princeton, she noticed that quite a few other top-tier schools shared a similar story, all in a remarkably brief time (from 1969 to 1974). She decided to broaden the topic from Princeton to include 15 colleges and universities in the United States and the United Kingdom. The book's title, "'Keep the Damned Women Out': The Struggle for Coeducation," is from a quote from a letter by a Dartmouth alumnus to the college's board of trustees to dissuade it from approving coeducation.

Malkiel's book, published by Princeton University Press, is a historical account of how the struggle for coeducation developed, the leadership and processes that followed, and the effects of that social change on institutions of higher education. The book is also about how men and women relate to one another and how educational opportunities opened to a segment of the population that didn't have access before.

To put the coeducation movement into context, one must look at what was going on in the late '60s and early '70s, Malkiel said.

"So much changed for colleges and universities in the 1960s as a result of the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the student movement, the women's movement," Malkiel said.

This coincided with a deliberate push to diversify the student body at colleges and universities. But the real trigger for change was that applications were falling off in the late 1960s. Said Malkiel, "Students these colleges and universities called 'the best boys' made plain that they wanted to go to school with girls. So Princeton, Yale and others decided to admit women to regain their hold on 'the best boys.'"

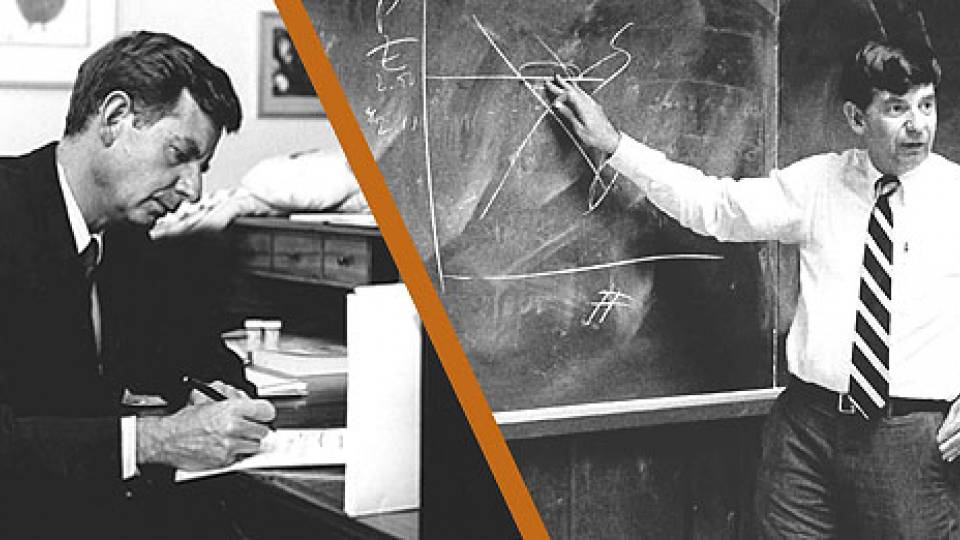

The late President Emeritus William G. Bowen, who was provost when Princeton was deciding to go coeducational, took a leading part in the ultimate decision. Bowen took on the task of convincing the president at the time, Robert F. Goheen, that coeducation made sense for Princeton, and Bowen also worked closely with a committee established to study the issue, ultimately convincing the trustees and the president to accept the change. The trustees voted in 1969 to admit women, and the first female undergraduates enrolled later that year.

Because the change was relatively quick, how to integrate women on historically male campuses hadn't been thought through, and most decisions were being made by men. At Princeton, for example, Malkiel said, "They knew they needed long mirrors … but beyond that, these men didn't know a lot about what was going to be necessary to do for women students."

How people view educated women has changed dramatically since the 1970s, but change comes slowly, Malkiel said.

"At Princeton, the student body is 50-50, in terms of the representation of undergraduate women, and there are significant numbers of women on the faculty," Malkiel said, but it is "not enough. The faculty doesn't yet reflect the full diversity of the undergraduate student body."

On the other hand, not only has Princeton had a female president, but it is "very common to have women deans and women vice presidents," noted Malkiel.

On women and men going to school together, Malkiel said, "it enriches the intellectual experience."