To curb the destructive illegal ivory trade, the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) announced in 2008 that it would suspend its ban on the international trade in ivory to allow a one-time legal sale of 108 metric tons of stockpiled ivory to China and Japan from four African nations. This partial-legalization was intended to flood the Asian market with legal ivory, driving black-market purveyors and the poachers who supply them out of business.

The move had the opposite effect, according to researchers from Princeton University and the University of California-Berkeley who have conducted a new analysis of the policy's global repercussions.

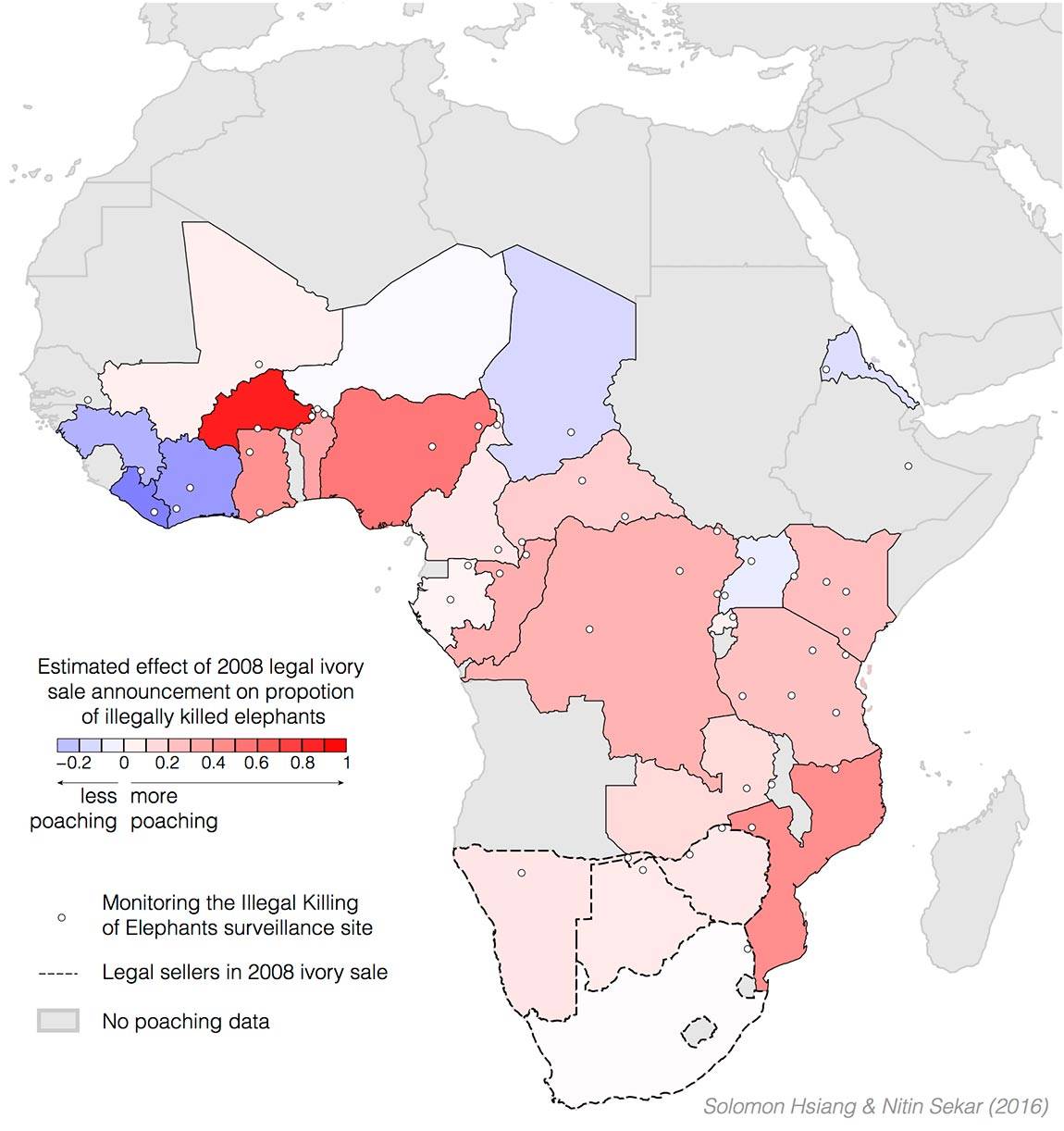

Since the announcement of the legal sale, illegal ivory production has increased by about 66 percent, while seizures of ivory being smuggled out of Africa have increased by approximately 71 percent, the researchers report in a working paper published June 13 by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The booming international black market for ivory — the United States is the second-largest market — is thought to have led to the slaughter of an estimated 100,000 elephants from 2011 to 2014.

Researchers from Princeton University and the University of California-Berkeley found that a one-time legal sale of 108 metric tons of stockpiled ivory that was intended to stifle elephant poaching in Africa actually expanded the black market for ivory and led to the slaughter of more elephants. The researchers found that the partial legalization stimulated new demand for ivory and made concealing illegal ivory easier. The booming international black market for ivory is thought to have led to the slaughter of an estimated 100,000 elephants from 2011 to 2014. (Photos by Nitin Sekar, AAAS)

The researchers found that the effects of the legal ivory sale actually expanded the black market for ivory and led to more elephant poaching in Africa. After the 2008 sale, observers reported that people's demand for ivory surged once it was legally available and had greater public visibility. At the same time, the presence of legal ivory in the market made it easier to conceal illegal ivory from the authorities — a phenomenon known as "masquerading."

These effects are not necessarily limited to ivory, the researchers said. Their work suggests that the partial legalization of some illegal products may in fact encourage black-market activity by attracting new customers who were previously unwilling to buy illegal products, and by reducing the risk to criminal groups — and thus the expense — of producing, transporting or selling those goods.

"The intuition that legalization will reduce illegal production is not always true," said co-author Nitin Sekar, an AAAS science policy fellow who initiated the study as a graduate student in Princeton's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

"The economic intuition was that if we allow the sale of some legal ivory in Japan and China, then there would be fewer people left to purchase it illegally. We found that that intuition was incorrect," said Sekar, who received his doctorate from Princeton in 2014. "The black market for ivory responded to the announcement of a legal sale as an opportunity to smuggle even more ivory."

The ivory market demonstrates that approaches to combating black markets need to be more nuanced than current policies, said co-author Solomon Hsiang, a Berkeley associate professor of public policy who started the project with Sekar as a postdoctoral researcher in Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Bids for legalizing illicit goods hinge on reducing prices so that illegal trade becomes unprofitable, Hsiang said. His and Sekar's work illuminates, however, that while prices may drop, so will expenses. At the same time, the customer base will likely increase as a once-stigmatized product becomes legally and socially acceptable.

"You can have a legalization event, you can have prices fall, but the production actually goes up. That's something that's not been appreciated," Hsiang said. "We can't just assume legalization's going to have one effect. It's going to have three effects — some demand satisfied, a potential increase in the consumer base and reduced cost of smuggling. The balance of those effects is going to matter.

"I used to be a strong believer in legalization as a crime-reducing policy, but this has really forced me to rethink that," Hsiang said. "Now, when people talk about legalization it may be smart in some cases, but in which cases is not as obvious. This is a case study for how wrong it can go."

Since the 2008 legal sale, illegal ivory production has increased by about 66 percent, while seizures of ivory being smuggled out of Africa have increased by approximately 71 percent. The sale briefly opened ivory trade between China and Japan and four African nations (in dash outlines) — clockwise from left, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Elephant poaching, however, has increased all over sub-Saharan Africa, as seen on the map above with red indicating more poaching since 2008 and blue equating to less. The white dots indicate sites for monitoring elephant poaching. (Image courtesy of Solomon Hsiang, University of California-Berkeley)

George Wittemyer, a Colorado State University associate professor of fish, wildlife and conservation biology, said that the study aptly captures how real-world markets for wildlife products can be much more complex and unpredictable than economic approaches to conservation acknowledge — and how devastating it can be when those policies fail.

"As far as I've seen, this is probably the most robust and thorough approach to looking at [the 2008 sale] event," said Wittemyer, who is familiar with the research but had no role in it. "There's a lot of nuance in wild-species trade in terms of the type of animal products people are using, if it can be harvested without harming the animal, what's being valued and the social stigmas attached.

"Using trade to conserve wild species is a really complicated social issue and it's hard to predict if it will be successful or not," he said. "The fact that you're dealing with the persistence of a species means that if you make a mistake, and your assumptions are wrong, the cost can be extinction or large-scale extirpation. That to me is really important to consider and a paramount concern."

If even partial legalization de-stigmatizes wildlife products and increases demand, as Sekar and Hsiang found, that could call into question the use of markets and legalization to control poaching, Wittemyer said.

"These economic mechanisms that we think are solutions can actually exacerbate the problems," he said. "The level of demand for ivory is currently unsustainable. We think that trade is a solution where you introduce enough product to inundate demand, but the evidence we see for elephants is that demand exceeds supply. As for outright bans, there is evidence this worked to reduce demand in Western markets for elephant ivory."

In the case of ivory, black-market activity rallied because the demand increased for a legal supply of a good that could not be legally or widely produced, Sekar said. In their paper, he and Hsiang noted that crocodile farms virtually eliminated the illegal trade in crocodile skins by adequately meeting demand.

Farms for elephants, rhinos, tigers and other slow-growing and wide-ranging species, however, are unfeasible. Thus, demand for products from these animals cannot be met through legal supplies. That demand may instead be met by exploiting the very limited and threatened natural populations, which are protected by law but prey to criminal gangs.

"Now that we have strong evidence that demand may actually go up for a product when you partially legalize it, the question is whether we are going to be able to meet that demand with legal versions of the product," Sekar said. "If not, we can assume that consumers are likely to end up buying it on the black market anyway."

For eliminating the black-market supply of products such as ivory, total bans on all trade, removal of the goods from the market (similar to firearms buy-back programs) and public campaigns aimed at reducing demand might be more effective than any form of legalization, Hsiang said.

"We saw that the poaching has remained high ever since the 2008 partial-legalization and part of it may be because ivory continues to circulate in the marketplace, providing cover to the illegal stuff," Hsiang said. "To fix this, you probably want to either ban trade entirely, or you want to try to get the stuff off the market."

On June 2, President Barack Obama issued a near-total ban on the sale within the United States of all products containing the ivory of African elephants. In the 1970s and 1980s, information campaigns about the brutality of ivory production helped reduce Western demand for ivory, and led to an international ban on the trade in 1989. Highlighting the need for a renewed public-awareness effort, Sekar and Hsiang cited research reporting that in China many people believe — wrongly — that ivory is taken without harming the elephant.

"It doesn't make sense to try to create a legal system for the ivory trade. In the most immediate sense, our study suggests that CITES resolutions proposing such trade should not be approved and that alternative means should be explored to help stem the poaching of elephants," Sekar said.

"We're not saying that legalization in general never works or that legalization always works," he said. "We're saying the policy needs to be designed to fit the endangered species in question."

The paper, "Does legalization reduce black market activity? Evidence from a global ivory experiment and elephant poaching data," was published June 13 as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.