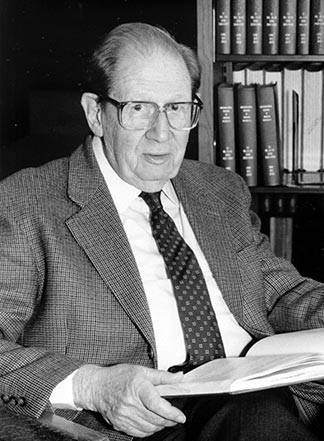

Carl Schorske, the Dayton-Stockton Professor of History, Emeritus, at Princeton University and an authority on the intellectual and cultural history of 19th- and 20th- century Europe, died Sunday, Sept. 13, 2015, in Hightstown, New Jersey. He was 100 years old.

Schorske gained international acclaim for his extraordinary blending of art history, European political and cultural life, international history, urban development, literary criticism, psychoanalysis, and the emergence of 20th-century culture.

He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1981 for "Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture," a collection of seven essays that paint a compelling picture of Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. The same year, he was chosen as an inaugural MacArthur Prize Fellow. He was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Princeton in 1997.

A native of New York City, Schorske earned his bachelor's degree at Columbia College and his doctorate from Harvard University. During World War II, he served in the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Schorske joined the Princeton faculty in 1969 after teaching at the University of California-Berkeley and Wesleyan University. At Princeton, he established the Program in European Cultural Studies, captivated undergraduates with engrossing lectures and blazed new paths of scholarship still being explored today. He transferred to emeritus status in 1980.

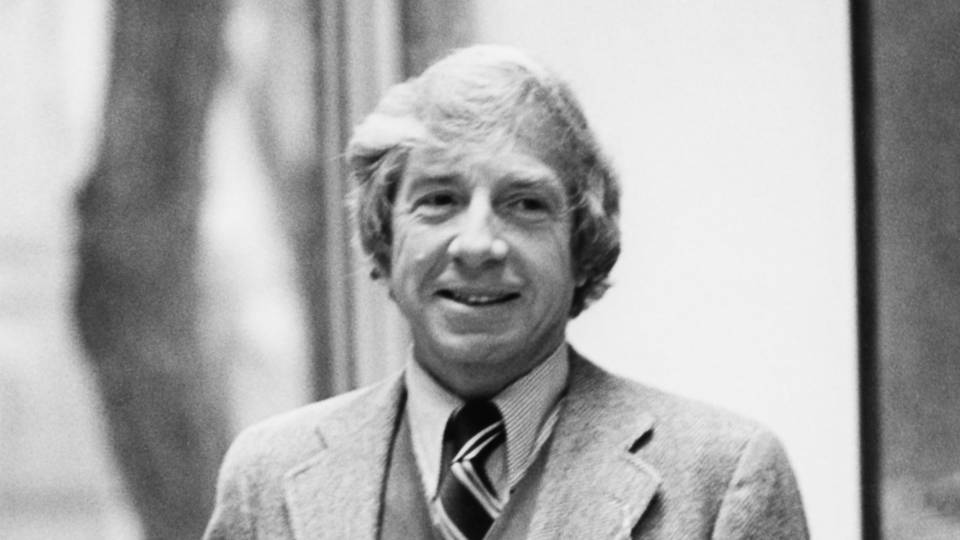

Arno Mayer, the Dayton-Stockton Professor of History, Emeritus, at Princeton had been a close friend and colleague of Schorske's since the 1940s.

"He became my mentor at the same time he became a friend because among all the scholars whom I met in my lifetime he was the most humane, the most human and at the same time one of the most original historians," Mayer said.

"Professor Schorske's work reshaped the study of European culture: he offered models for thinking about the ways that a generation came together, how its members were affected by the politics and the daily life of the cities they lived in, that historians are still following up on, half a century after he began to publish in the field and 35 years after 'Fin-de-Siècle Vienna' appeared," said Anthony Grafton, the Henry Putnam University Professor of History at Princeton. "His work inspired brilliant younger scholars to investigate the Viennese world that he opened up and to apply methods like his to other cases."

Schorske's work on Austria drew praise in that nation as well. In 1979, he was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art, First Class, bestowed upon "scholars or artists of high merit who have helped the world gain better knowledge of Austrian culture and science." In 1986, he was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Salzburg.

Debora Silverman, who studied under Schorske as an undergraduate and a graduate student at Princeton, said Schorske's approach succeeded in part because he was able to call on a deep understanding of many fields.

"Schorske looked at a whole array of different media — he called them branches of cultural activity," said Silverman, who is a professor and the University of California Presidential Chair in Modern European History, Art and Culture at the University of California-Los Angeles. "It was widely admired but it was difficult to emulate because he mastered so many different skills of so many disciplines. The way he writes captures things in ways one person could rarely do."

Schorske's lectures were legendary. In 1966, while at Berkeley, he was recognized by Time magazine as one of the 10 "great teachers" in the country. He was remarkable even when things didn't go so well, Grafton said.

"One day, he started a lecture; stopped; started again; then stopped, looked up at the class and said, 'I'm sorry, it's not working today. I'll see you next time.' He left the room to a standing ovation," Grafton said. "Professor Schorske cared deeply about teaching. He told me, and wrote, that he saw it as a vocation, in the old sense. He simply could not give his students less than his best."

David Abraham, who was an assistant professor of history at Princeton, said he learned valuable lessons about teaching from Schorske.

"As a preceptor for Schorske, I learned the power of expression and evocation in the classroom and the lecture hall, even though I was never able to duplicate his remarkable ability to speak extemporaneously for a full hour, holding scores of students riveted to their chairs," said Abraham, now a professor at the University of Miami School of Law.

Told once that he had been described as a great lecturer, Schorske replied: "No, I'm not a great lecturer. I'm a good one, though!" Schorske said in "Conversations on the Character of Princeton," a book published by the University in 1986. "The great ones of the old school carefully prepared their lecture texts in advance and delivered them for rhetorical effect as well as substance. My style is spontaneous — which takes enormous energy: You have to be like a tensile spring. But by thus doing your thinking out loud you demonstrate the process by which one gets learning."

Outside of his academic work, he was known as an accomplished musician; a marvelous dancer, especially of the waltz; and, with his wife Elizabeth, a gracious host at his Princeton home.

Schorske is survived by his sons, Carl Theodore (Ted) of Philadelphia; John of Boston; and Richard of San Rafael, California; daughter Ann Schorske Edwards of Silver Spring, Maryland; three grandchildren, Carina del Valle Schorske, Kai Schorske Peattie and Katherine Edwards; and two great-grandchildren, Lukas Smith and Safira Smith.

A memorial service will be held at the University at a later date.

Memorial contributions can be sent to Doctors Without Borders.