Samuel Hunter, professor of art and archaeology, emeritus, at Princeton University and a renowned modern and contemporary art scholar, died of natural causes on July 27 in Princeton, New Jersey. He was 91.

"Sam Hunter came to Princeton in 1969 as a well-established historian of modern and contemporary art who had by that time played a prominent role in his field for more than 20 years as a professor, curator, museum director, editor and critic," said Michael Koortbojian, the M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Art and Archaeology and chair of the Department of Art and Archaeology.

At Princeton, Hunter also was the faculty curator for modern art at the Princeton University Art Museum, where, with graduate students, he organized exhibitions of the works of Robert Motherwell (1973) and Josef Albers (1971), and selections from the Michael and Ileana Sonnabend Collection (1985). He previously served as director of the Jewish Museum in New York City.

In the early 1960s, while on the faculty at Brandeis University, he became the founding director of the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis — where he built the museum's acclaimed, seminal collection of modern and contemporary art, which includes works by many artists who were featured in the Fine Arts Pavilion exhibition Hunter curated for the 1962 World's Fair in Seattle.

Earlier in his career, he served as chief curator and acting director at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, associate curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York where he organized the first major museum shows of the work of David Smith (1957) and Jackson Pollock (1956), and art critic and associate art editor at The New York Times. He also organized the American sections of the Venice Biennale (1976) and the São Paolo Bienal (1956). His honors and awards include an honorary doctorate from Brandeis in 2001, an Academico degree from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, Italy, in 1994 and a Guggenheim fellowship in 1971.

"He epitomized a versatility that had long-dominated the study and criticism of modern and contemporary art, something evident not only in the breadth of his professional experience, but in the wide range of his many books and publications, and in his involvement in the training of practicing artists," Koortbojian said.

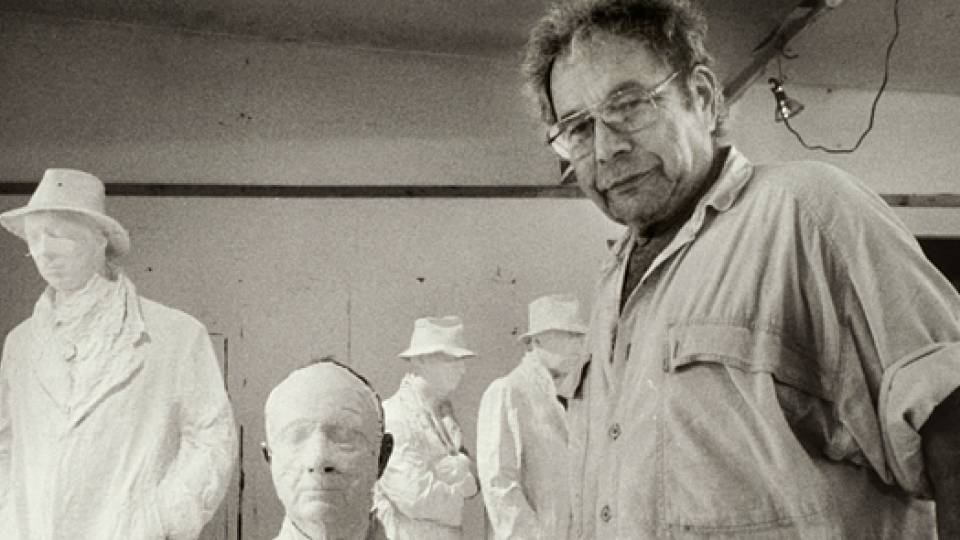

Hunter was the author of over 50 books — including "Tom Wesselmann: Metalworks" (1991); "Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture" (second edition, 1985) and "American Art of the 20th Century" (1973), as well as books on Larry Rivers, Isamu Noguchi and George Segal, among others — and more than 150 essays, museum and gallery catalogues, and articles on art history and artists.

"Sam was one of the pioneers of the study of modern art as an academic field," said Hal Foster, the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917, Professor of Art and Archaeology; the co-director of the Program in Media and Modernity; and a 1977 alumnus who first met Hunter when he took his survey course of 20th-century art as an undergraduate.

Foster noted that Hunter's distinguished career in the museum world before coming to Princeton had a significant impact in the classroom. "Sam brought to his students the urgency of a player active in the field. I like to think that the lively interchange between modernists in the academy and the museum today is a living testimonial to Sam and his contemporaries," Foster said.

One of those students was Anne Cheng, professor of English and African American studies and a member of the Class of 1985, who said that Hunter "once took a chance on a very green undergraduate" and allowed her to take his advanced graduate seminar on modern American art in her junior year.

"That seminar changed my life," Cheng said. "Although I was an English literature major who thought she knew what criticism was, it was Sam Hunter who really taught me what critical discourse is: a mode of thinking."

Cheng noted that her experience in the seminar fostered "a lifelong passion for modernism and for visual culture that has been the foundation of my intellectual life" and continues to influence her scholarship today. "As my research turns more and more toward issues of the visual, I realized that I am coming back into a love bred by Sam Hunter. He will always be a major part of what Princeton means to me. I will remain indebted to his kindness and generosity as a teacher forever," she said.

Hunter was born in Springfield, Massachusetts. After graduating from Williams College in 1943, he served as a naval line officer in the Pacific theater in WWII. After the war, he studied art history in Florence and at the American Academy in Rome on a Hubbard Hutchinson Fellowship in art history and criticism.

At Princeton he taught a range of courses including "Foundations of Modern Art," "Masters and Movements of 20th-Century Art," "Seminar in Contemporary Art," "Seminar in Modern Painting and Sculpture" and "Contemporary Art Studies."

Many of his students went on to forge prominent careers in the art world and academia. Hugh Davies, the director and chief executive officer of the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, earned his bachelor's degree in art history in 1970, his MFA in art history in 1972 and his Ph.D. in 1976, with Hunter as his adviser throughout.

"Sam was a profound influence, role model and mentor. I would not have become a museum director without his dynamic example," said Davies, who was a co-curator with Hunter of the 1976 Venice Biennale.

He and his fellow graduate students would go to New York to meet Hunter, who took them to galleries, museums, private collections and artists' studios. "Rather than leaving us to languish in libraries and learning from slides he generously used all his great contacts to immerse us in the contemporary art world," Davies said.

Davies' wife, Sally Yard, earned her MFA at Princeton in 1975 and her Ph.D. in 1980, also with Hunter as her adviser. She is a professor of art history at the University of San Diego; her courses center on modern and contemporary art in the United States and Europe. Her work on the relationship of art and its publics includes the book "Christo: Oceanfront," published by Princeton University Press.

"Sam plunged us into the art world with vigor and élan, and the realm of contemporary art was really his domain,” Yard said. “The impact was vast, and we immediately found ourselves working with artists like Christo, Claes Oldenburg and Toni Smith. Sam took action and meant to play a role in the unfolding, as well as the chronicling, of art."

Hunter is survived by his wife, Maïa Hunter, and their son, Harry, as well as daughters Emmy and Alexa from his previous marriage to Edys Merrill, and one grandchild, Isabella.