Highly purified crystals that split light with uncanny precision are key parts of high-powered lenses, specialized optics and, potentially, computers that manipulate light instead of electricity. But producing these crystals by current techniques, such as etching them with a precise beam of electrons, is often extremely difficult and expensive.

Now, researchers at Princeton and Columbia universities have proposed a method that could allow scientists to customize and grow these specialized materials, known as photonic crystals, with relative ease.

"Our results point to a previously unexplored path for making defect-free crystals using inexpensive ingredients," said Athanassios Panagiotopoulos, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Princeton. "Current methods for making such systems rely on using difficult-to-synthesize particles with narrowly tailored directional interactions."

In an article published online July 21 in the journal Nature Communications, Panagiotopoulos and colleagues propose that photonic crystals could be created from a mixture in which particles of one type are dispersed throughout another material. Called colloidal suspensions, these mixtures include things like milk or fog. Under certain conditions, these dispersed particles can combine into crystals.

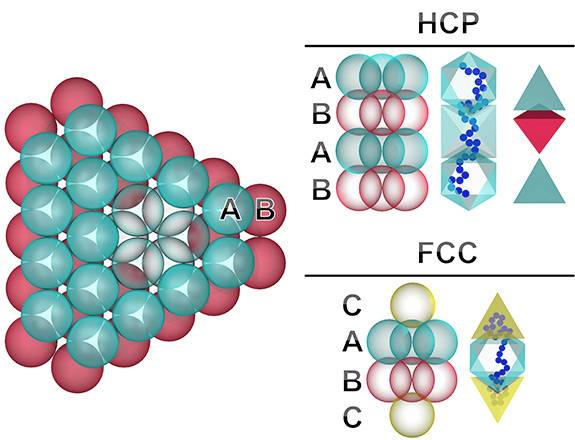

Princeton and Columbia researchers have discovered a way to ensure that tiny particles settle into a single, uniform crystal structure. Previously, the particles assumed a variety of structures, which made the resulting crystals unsuitable for high-performance uses. At left, particles form the initial two layers of a crystal, labeled A and B. With the addition of the third layer, the crystal forms one of two possible shapes, show in side views at right. The vertical blue string to the right of each crystal shows a chemical chain that the researchers add to the mix to force one structure to form versus the other. (Image courtesy of Nathan Mahynski, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering)

Creating solids from colloidal suspensions is not a new idea. In fact, humans have been doing it since the invention of cheese and the butter churn. But there is a big difference between making a wheel of cheddar and a crystal pure enough to split light for an optical circuit.

One of the main challenges for creating these optical crystals is finding a way to create uniform shapes from a given colloidal mixture. By definition, crystals' internal structures are arranged in a pattern. The geometry of these patterns determines how a crystal will affect light. Unfortunately for optical engineers, a typical colloidal mixture will produce crystals with different internal structures.

In their paper, the researchers demonstrate a method for using a colloidal suspension to create crystals with the uniform structures needed for high-end technologies.

Essentially, the researchers show that adding precisely sized chains of molecules — called polymers — to the colloid mixture allows them to impose order on the crystal as it forms.

"The polymers control what structures are allowed to form," said Nathan Mahynski, a graduate student in chemical and biological engineering at Princeton and the paper's lead author. "If you understand how the polymer interacts with the colloids in the mixture, you can use that to create a desired crystal."

The researchers created a computer model that simulated the formation of crystals based on principles of thermodynamics, which state that any system will settle into whatever structure requires the least energy. Panagiotopoulos' group analyzed the equilibrium state of different possible crystal shapes to understand how they were affected by the presence of different polymers.

They found that when the crystals formed, tiny amounts of polymer were trapped between the colloids as they came together. The polymer looks like mortar in a stone wall, although the researchers say it has no adhesive property. These polymer-filled spaces, called interstices, play a key role in determining the energy state of a crystal.

"Changing the polymer affects which crystal form is most stable," Mahynski said. "As the crystal forms, the polymer helps set the crystal's shape."

The polymer and the forming crystal work like a lock and key — they fit together in the crystal structure with the lowest energy state. Because of this, scientists can use their knowledge of polymer physics to tailor crystal structures.

Because the researchers conducted their analysis using computer modeling, they cautioned that experimentally reproducing the results in a lab presents some difficult challenges. One early concern involved the uniformity of colloids in the suspension; models often assume colloids are all the same shape and size but this rarely occurs in natural systems. Anticipating this, the researchers tested their theory using a non-uniform solution.

"One of the things we did in our study was to look at realistic systems that were realizable in the lab, and it appears that the phenomenon that we describe is robust," said Sanat Kumar, a professor and chair of chemical engineering at Columbia and a researcher on the project. "That tells us that there is no conceptual problem to realizing this in the lab."

Graduate student Nathan Mahynski, shown here, worked with Professor Athanossios Panagiotopoulos to develop a method of creating high-performance crystals with a precise ability to manipulate light. Such crystals could be used in "optical circuits" that manipulate information encoded in light rather than in electricity. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski for the Office of Engineering Communications)

Gravity could also pose a problem for experimenters, although Kumar pointed out that similar experiments have overcome this difficulty. Gravity causes crystals to filter to the bottom of a container and pack in mismatched layers. This can make it very difficult, and perhaps impractical, to try to produce the crystals by using a colloid mix in a tank.

But Mahynski said there are several techniques that could avoid problems. For example, to deal with gravity, researchers could create the crystals in a very thin film. That approach should avoid the disruption of gravity pulling the crystals to the bottom.

It also could be important to select the right size of colloid and type of polymer for a successful experimental result. Panagiotopoulos said that one possible path for these ideas to be experimentally verified will be to use polymer chains that are stiff, such as double-stranded DNA, together with micrometer-sized colloids.

Besides Panagiotopoulos, Kumar and Mahynski, the paper's authors include Dong Meng, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia. Support for the project was provided in part by the National Science Foundation.