On a recent summer evening, a group of 17 rising seniors from colleges across the country were discussing Russia and the European Union in Robertson Hall on the Princeton campus.

The students are part of the international policy workshop, "U.S.-EU Cooperation on Conflict Resolution," in the Junior Summer Institute (JSI), a seven-week-long program hosted by the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs that is designed to prepare students for advanced degrees and careers in public and international affairs.

Isaiah Wonnenberg (left) of the University of South Dakota, Hayley Laity (center) of the University of California-Berkeley and Maria Luisa Zeta Valladolid (right) of Colby College listen to the policy discussion.

In addition to the international policy workshop, JSI offers the domestic policy workshop, "Social Impact Bonds." Led by Richard Roper, who earned his master in public affairs from the Wilson School in 1971, the workshop immerses 14 students into the growing field of innovative finance that aims to achieve social good.

On the night of June 30, George Bustin, a 1970 Princeton graduate and senior counsel at the international law firm of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, led the discussion. An expert in EU law who also served 15 years as an international legal counsel to the Russian Ministry of Finance, he offered two principal objectives for his talk: to outline the key institutional features of the EU's foreign and security policy system; and to examine Russian perspectives on geopolitical developments since the fall of the Soviet Union.

George Bustin, a 1970 graduate of Princeton, discusses Russia and the European Union in the workshop.

"As Bismarck said, 'Russia is never as strong or as weak as she looks,'" Bustin said. "That maxim is an important one to be kept in mind by anyone who wants to understand Russian policy."

Bustin began his presentation with a short video of a flash mob dance next to Moscow State University in February 2012 and explained that because of the group's exuberance and spontaneity, such an event would have been unthinkable under Soviet rule.

"The people who organized the flash mob are students at Moscow State University. This is the demographic that will eventually constitute the intellectual and political elite of Russia," Bustin said. "Their ideals and their ambitions do not bode well for the type of authoritarian regime maintained by Russian President Vladimir Putin."

For the next two hours, Bustin touched on real-time topics ranging from perspectives on EU and Ukrainian agreements, Russia's place in the world, economic policies put forth by Putin, and Russian energy problems.

Such exposure to high-level officials and practitioners is what attracted Maria Luisa Zeta Valladolid of Colby College to the program. She said she values learning directly from experts in the field.

"We're a generation that gets information from a lot of different places, and it's hard to discern where the truth lies," said Valladolid, who asked Bustin about institutional change in Russia by the younger and rising generations. "When we're listening to experts, I feel more confident about the subject and the sources of knowledge because we're learning from someone who has experience in the field."

Jalita Moore of American University, above, said the opportunity to analyze topics openly is a defining quality of the JSI program.

Jalita Moore of American University added that while students are privileged to be able to interact with high-level officials and speakers, the opportunity to analyze topics openly was something that set the presentation and the JSI program apart.

"Engaging in discussion and being able to ask questions, instead of being lost in a world of social media and Internet articles, is important," said Moore. She added that Bustin's focus on Russian energy problems reinforced her view that international policy is domestic policy, as relationships with other countries affect what happens in the United States.

Classes and workshops will culminate in a formal presentation, when students in the domestic and international policy workshops present policy analyses to a panel of practitioners who will critique their work.

James Gadsden, a 1985 Mid-Career Fellow at Princeton and former U.S. ambassador to Iceland, led the international policy workshop. Now in his seventh year as a JSI instructor, he said he returns annually because he enjoys watching students develop their analytic skills from the start of the program to their final presentations.

"The students reverse roles, where they're not analyzing somebody else's work, but they're preparing analytic pieces to present to a panel of practitioners," said Gadsden, who is also a senior counselor for international affairs at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. "To see how the students rise to the occasion of responding with great skill and expertise and to see the pride in them when they do this successfully is why I come back year after year."

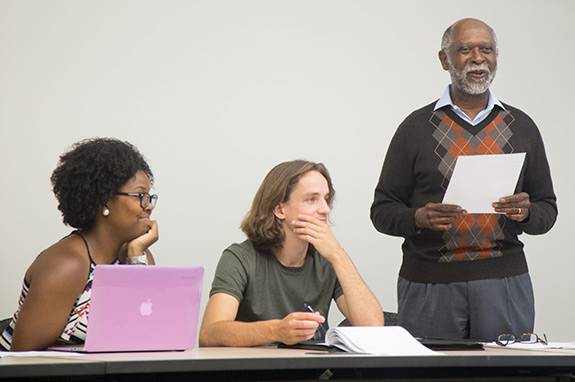

Raven Tukes (left) of the College of the Holy Cross and Matej Jungwirth (center) of Beloit College participate in the international policy workshop in the JSI program. Gadsden (right) is in his seventh year as a JSI instructor.

For nearly 30 years, JSI, which is part of the Public Policy and International Affairs Fellowship Program, has equipped students with skills that are essential for policy analysis: microeconomics, statistics, writing, public speaking, organization and time management. In addition to the Wilson School, JSI programs are hosted at Carnegie Mellon University, the University of California-Berkeley and the University of Michigan.

This year's JSI program at Princeton includes 31 students from 24 colleges and universities. Students hail from 17 U.S. states and six countries — Afghanistan, Brazil, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Liberia and Peru — and represent 25 majors.

The students are chosen for the institute based on a demonstrated commitment to public service, and an interest in and commitment to cross-cultural and social issues. Each student enrolled in the program is fully funded and receives financial support for all program expenses.

Gilbert Collins, who participated in JSI as a Harvard undergraduate before receiving his Master in Public Affairs from the Wilson School in 1999, is director of JSI and of graduate student life in the Wilson School and underscores the value of the program.

"The Woodrow Wilson School plans to maintain its strong commitment to the Junior Summer Institute well into the future," he said. "It has proven its strength in equipping and motivating students for further careers and studies in public policy."