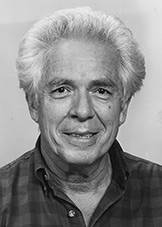

Harold Kuhn, a Princeton mathematician who advanced game theory and brought mathematical approaches to economics, died of congestive heart failure in New York on July 2. He was 88 years old.

Kuhn, who received his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1950, taught at the University for 37 years and retired in 1995 as professor of mathematical economics emeritus. He was widely recognized for his scholarship and respected for his thoughtful approach to teaching and for his service to the University.

Kuhn wrote a dissertation in geometric group theory advised by Professor Ralph Fox. Concurrently, he began a long collaboration with Professor Albert Tucker and fellow graduate student David Gale exploring and developing the emerging fields of nonlinear optimization and game theory, which focuses on the behavior of decision makers whose choices affect each other. Another fellow student was John Nash, and in 1994, Kuhn was invited by the Nobel Prize committee to chair a panel discussion of Nash's work, on the occasion of Nash's award of the Nobel Prize in economics.

In 1951, Kuhn and Tucker described what are known as the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions for nonlinear programming, now an economics staple that address optimization within constraints. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Kuhn was involved in organizing conferences in game theory.

"Game theory blossomed in Princeton in the mid-20th century. Kuhn was a key member of a brilliant group that ushered it in, which included the genius John von Neumann and Nobel Prize winners John Nash, Lloyd Shapley and Robert Aumann, amongst other greats," said Dilip Abreu, the Edward E. Matthews, Class of 1953, Professor of Finance and professor of economics at Princeton. "Kuhn's now-standard formulation of extensive form games completely eclipsed von Neumann's own, and his results on imperfect recall, mixed and behavioral strategies continue to stimulate, intrigue and delight."

In 2004, the journal Naval Research Logistics established an annual "best paper" award in Kuhn's honor, citing a "pioneering" 1955 Kuhn paper, "The Hungarian Method for the Assignment Problem," as the best paper representing the journal since its founding.

"Professor Kuhn's enduring contributions to optimization, discrete and continuous, linear and nonlinear, from its earliest days in the 1950s, are legendary," the journal's citation said. "He is a man who was in the right place, at the right time, with the right stuff."

Kuhn taught undergraduate and graduate courses in both the economics and mathematics departments on topics including price theory, mathematical economics, trade theory and mathematical programming.

Harold T. Shapiro, president of the University emeritus and professor of economics and public affairs, took several of Kuhn's courses while a graduate student and said he excelled at explaining difficult material.

"He was extremely well organized and thoughtful," Shapiro said. "He understood the challenge that faced the students in the problems he tried to elucidate."

Kuhn had a significant impact on students outside the classroom as well. In the late 1960s, he wrote a policy document known as "Students and the University" that led to broad changes in the participation of students in the governance of Princeton. Its successor document, "Rights, Rules and Responsibilities," retains a key role in defining students' relationship with the University.

During that period, he also served on the Committee of the Structure of the University, which designed the Council of the Princeton University Community. The council, known as CPUC, continues today to give the University's constituencies a voice in the institution's governance.

Joseph Kohn, professor of mathematics emeritus, said Kuhn was interested in social issues broadly and was "very eloquent" in expressing those ideas in discussions that centered on the University.

"He was an inspiring teacher and a good citizen," Kohn said.

Kuhn, born in 1925, served in the Army from 1944 to 1946 and completed his bachelor's degree at the California Institute of Technology in 1947. After completing his Ph.D. at Princeton, he was a Fulbright Scholar in Paris. He was an instructor at Princeton and spent seven years on the faculty of Bryn Mawr College before returning in 1959 to Princeton, where he would spend the rest of his career.

He was a Guggenheim Fellow in 1982-83 and served as president of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

Kuhn was a consultant to government organizations and to several companies, and was senior consultant and member of the board at research firm Mathematica Inc. from 1961 to 1983. At Mathematica, he directed projects for the Atomic Energy Commission, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Department of Transportation.

Abreu said he came to understand the breadth of Kuhn's professional work and personal interests after arriving at Princeton as a graduate student in 1980.

"Everything about Harold was dazzling and enviable, from his mythic origins in the golden age of game theory to his affable sophistication and deep February tan," Abreu said. "His wide-ranging interests encompassed modern art and design, university governance and civil liberties."

Specifically, Abreu noted Kuhn's long association with the American Civil Liberties Union and participation in a full-page advertisement in the New York Times protesting actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 2009, Kuhn returned to campus to speak about the early days of game theory to undergraduates taking the course "Theory of Games." Kuhn and Nash spoke about the evolution and application of their work.

As the session came to an end, a student asked what course Kuhn would take if he were an undergraduate again. He answered by urging the students to explore a range of mathematical fields.

"It's all beautiful," he said.

Survivors include his wife Estelle of New York City; son Clifford (Katherine Klein) of Atlanta, and their children Joshua and Gabriel Klein-Kuhn; son Nicholas (Beth) of Charlottesville, Virginia, and their children Michael (Anushree Sengupta), Jeremy, and Emily; son Jonathan (Michele Herman) of New York City and their children Lee and Jeffrey.

Memorial donations may be made to the American Civil Liberties Union.