Somewhere, deep in the sawgrass blazing green under the summer sun, a killer lurked.

Moments before, school teachers Michelle Hill and Amber Koney crunched ashore a salt-marsh island in New Jersey's Barnegat Bay in a fiberglass skiff with a handful of other educators-turned-summer researchers. They toted stakes and a wire cage, excited to protect the eggs they had watched a diamondback terrapin — a near-threatened turtle species — lay the day before in a slightly raised bare patch of dry sand.

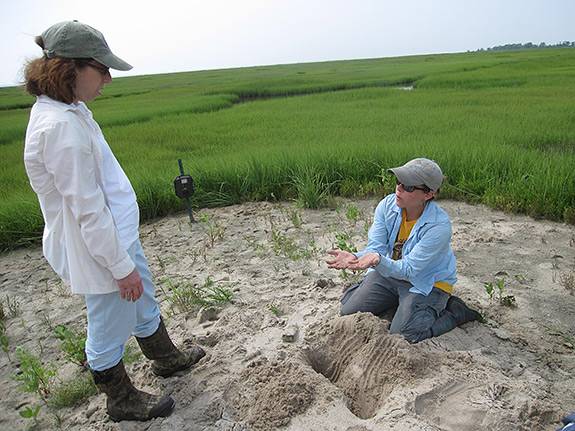

Now the 13-inch-deep hole was empty. Around it, scratches in the sand and tracks from something much bigger than a turtle. As Koney inspected the hole, Hill, hands on her hips, looked out over the marsh, but only the wind moved, making white ripples in the sawgrass.

Play the "In QUEST, Questions Are the Answer to Better Teaching" video.

Experiences such as this are the essence of the QUEST program run by Princeton University's Program in Teacher Preparation in collaboration with the departments of geosciences and of ecology and evolutionary biology. Each summer, select K-12 science teachers from New Jersey such as Hill and Koney become the students, spending a week with university-level researchers in the lab experimenting, or in the field observing and collecting evidence for self-designed research projects.

This summer QUEST included a program based at the state-owned Lighthouse Center for Natural Resource Education in Waretown, N.J., where teachers carried out research related to diamondback-terrapin conservation (see video). A second, experiment-based program held on Princeton's campus and led by Princeton Assistant Professor of Geosciences David Medvigy focused on human impacts on local climate.

In keeping with its long-form name — Questioning Underlies Effective Science Teaching — the program is intended to help participants become more effective teachers by becoming more inquisitive scientists, said Anne Catena, the Teacher Prep Program's director of professional development. Like any researcher, the teachers must think through, adjust to and even pursue the uncertainties of research. The teachers take back to their students the importance of learning through active and open thinking.

"This program is built on the importance of being able to pose and ask questions, and gather evidence from the data to discover or learn something," Catena said. "That gets the learner more involved in the process instead of just being a receptacle of information."

One group of teachers in QUEST undertake a weeklong session in the field observing and collecting evidence for self-designed research projects, including a program based at the state-owned Lighthouse Center for Natural Resource Education in Waretown, N.J., where teachers carry out research related to conservation of the near-threatened diamondback-terrapin. Participants make original findings that can help scientists better understand the pressures the species faces. This year, the projects specifically examined the impact of Hurricane Sandy on terrapin nesting and survival. (Photo by Tara Thean)

For the July 8-12 Lighthouse Center session, the teachers were provided with everything they needed for a week in New Jersey's coastal pine forest — except answers, said Koney, a third-grade teacher at Dutch Neck Elementary School in West Windsor. "They don't answer our questions and we have to figure out everything for ourselves," she said. "As a teacher you also don't want to give kids the answer — they need to find the path themselves. It can be tempting to just tell the answers, but that's not allowing the kids to figure things out."

Staying connected to nature also is important, said Hill, a seventh-grade science teacher at Hillsborough Middle School, who aims to foster a respect for the natural world in her students. Fond of turtles since she was little, Hill hopes to have turtles in the classroom, and what she learns at QUEST will help her make it more educational.

"I want them to have that experience not only for teaching responsibility, but also for teaching them respect for living things other than humans because the age group I teach struggles with that sometimes. They're very much an indoor generation," Hill said.

The pillaged nest gave Koney and Hill a lot to try to figure out. For their project, the two teachers explored whether predators of terrapin nests can be identified by scratch and dig patterns as well as by droppings, or scat. A camera set up to monitor the nest had captured the culprit — a red fox!

With the predator identified, Koney and Hill searched for evidence unique to a fox. Because all the eggs were gone, they wanted to know if that means foxes eat them whole, and if that differs from the habits of other turtle-egg scavengers such as raccoons. There was only one way to know.

"Actually, the daring raid helped us," said Hill as she and Koney combed the ground nearby for egg-laden fox feces. When the teams presented their results at the end of the week, Hill and Koney reported that foxes and raccoons ravage nests in distinct ways. Thus predators can indeed be identified by footprints and scat, which may sometimes be better than other methods for documenting past nest violations.

QUEST is intended to help participants become more effective teachers by becoming more inquisitive scientists. Teachers are expected to find their own answers. Jules Winters (right, with Anne Catena, the Teacher Prep Program's director of professional development), lead scientist and facilitator of the QUEST program at Barnegat Bay, has spent five years studying diamondback terrapins as a doctoral candidate at Drexel University. Though she knows the island "up and down," her knowledge was off limits: "I'd rather … have them make their own experiences through their own eyes." (Photo by Tara Thean)

Don't get too comfortable: Teachers become the students

Being in the role of the student keeps teachers mindful of the learner's perspective, said Steve Carson, a facilitator for QUEST and a seventh-grade science teacher at John Witherspoon Middle School in Princeton. Carson, who once worked at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory on Princeton's Forrestal Campus, has been an instructor with QUEST for 16 years. This year, Carson helped lead the July 8-12 session based on Medvigy's research. The teachers learned about and conducted numerous experiments related to water cycles, watersheds, precipitation and other climate topics.

"We have people who are very motivated, very interested and have a sense of purpose for learning this stuff. They're all very eager to learn, try new things and take away new ideas," Carson said. "One comment that always comes up is that it reminds them of how it feels to be a student. That helps them think more about what their students are thinking. They know that discomfort level [of not having all the answers] and it may change how they engage with the student."

A discomfort familiar to Peter Martens, a trained engineer who teaches 11th- and 12th-grade physics at West Windsor-Plainsboro High School, as he saturated a paint tray of bare dirt with a spray bottle and recorded the amount of runoff during Medvigy's session. Some teachers around him did the same experiment, while others worked with a paint tray of dirt with grass growing from it. The idea — drawn from the effects of deforestation — was to test how vegetation influences the uptake of water into soil.

"It's basically applying physics under a normal setting, but it's throwing a curveball at me because it's not the usual," said Martens, who has no earth-science background. "This whole program gets me out of my comfort zone. This new kind of thinking tweaks something in the mind so that you have a different tool in your toolbox. In your mind, you then mix and match that with what you already have."

Jules Winters, lead scientist and facilitator of the QUEST program at Barnegat Bay, knows the island "up and down," she said. As a doctoral candidate at Drexel University, Winters has spent five years studying diamondback terrapins in New Jersey coastal marshes. But her knowledge was off limits to the teachers in QUEST. The island is like a classroom, Winters said. She can either read from the "textbook" of her experiences, or have the teachers learn (often prompted by questions from Winters) through their own observations and analyses.

"I'd rather 'close' that book and have them make their own experiences through their own eyes," Winters said. "They get really frustrated and sometimes want to kill me, but I don't really get an urge to break. I really want them to figure it out on their own."

An on-campus QUEST session puts teachers in the lab with university-level researchers conducting experiments that can transfer to the classroom. The most recent program, led by Princeton Assistant Professor of Geosciences David Medvigy (left), focused on human impacts on local climate. Steve Carson (center), a QUEST facilitator for 16 years and a seventh-grade science teacher at John Witherspoon Middle School in Princeton, said the program gets teachers out of their comfort zone of knowing all the answers. Princeton Charter School mathematics teacher Sabina Khachatrian (right) measures water runoff in dirt-filled paint trays (with and without grass) meant to simulate the effects of deforestation. (Photo by Morgan Kelly, Office of Communications)

No project is an island: Real research with real results

The teachers' original ideas can result in discoveries that help scientists studying diamondback terrapins better understand the pressures the species faces, Winters and Catena said. For instance, the 2012 group learned that crows, which are not native to the island, regularly ransack nests for fresh eggs. This year, the projects specifically examined the impact of Hurricane Sandy on terrapin nesting and survival.

"This is real research they're contributing to," Catena said, adding that more fieldwork programs are being developed for the QUEST repertoire. "This is not made up so that they have an activity. This is research that scientists don't have time or money to do. It's not contrived."

Edward Leung, a Princeton sophomore in the Teacher Prep Program, pounds a paint tray of dirt with a rubber mallet to simulate the stress bulldozers inflict on forest soil. QUEST focuses on an inquiry-based approach to classroom lessons intended to better engage students, Leung said. (Photo by Morgan Kelly, Office of Communications)

"This group is the only one collecting data on terrapins this calendar year, so they're really important," Winters said. "The idea of their projects is that the work has to be reciprocal. The teachers are gaining experience and the researchers are getting real data."

That real data relates to a species feeling pressure on many sides, both natural and manmade. Diamondback terrapins inhabit swamps and marshes along almost the entire east coast of the United States. Despite their wide distribution, they are threatened by pollution, abandoned crab traps, poachers, roads and a variety of other ills.

In many cases, the turtles fall victim to the tenacity of their own habits, Winters said. In her research, she found that bulkheading, or seawalls, have little effect on the diamondback terrapin's determination when it comes to laying eggs. They scramble around bulkheading, and over roads and docks, often to their peril. Yet research shows the turtles are entirely cognizant of these things. "They have all the ability to respond to the human world — they just don't," Winters said.

Strengthening lessons, learning from colleagues

By experimenting and working in the field, teachers in QUEST make connections between science and teaching they might not otherwise.

In the campus session, Princeton Charter School teacher Sabina Khachatrian simulated the stress bulldozers inflict on forest soil by pounding her paint tray of dirt with a rubber mallet. These lessons appealed to Khachatrian as an environmentalist but had seemingly little connection to her work as a fifth- through eighth-grade mathematics teacher. Or so she thought. The previous day, she built a rain gauge and realized that it couples earth science and math, making for a practical and relevant class experiment.

Peter Martens, who teaches 11th- and 12th-grade physics at West Windsor-Plainsboro High School, and Sabina Khachatrian learned about and constructed a rain gauge during the QUEST session led by Medvigy. A trained engineer with no earth-science background, Martens said the experiments in QUEST expand on the knowledge he already has to provide "a different tool in your toolbox" to call upon in the classroom. (Photo by Mary Elizabeth Hughes, for QUEST)

"I always talk to my students about preserving the environment," Khachatrian said. "I am really looking forward to connecting life to mathematics to teach students to connect any kind of math to real-life situations. The first thing students ask is, why are we learning equations, why are we learning this or that? I think this program is the best way to enrich math class."

At Barnegat Bay, another group of teachers examined the plants around terrapin nests. The idea was that the turtles might avoid plants with larger roots because the roots pull moisture away from the eggs, explained Ginny Gallagher, a sixth-grade teacher at Hillsborough Middle School. The group counted succulent plants around nests they found, thumbing through a guide to tidal vegetation. The nests varied in position — some were in full sun, others surrounded by as many as 50 plants. But there was a pattern, Gallagher said.

"From looking at the nests, the area is clearer where they decide to lay," Gallagher said. "They're not in deep brush, and the nest area is open with plants around it."

Gallagher worked alongside David Jungblut, a ninth-grade science, environmental science and research science teacher at Oakcrest High School in Mays Landing. Jungblut often incorporated research and fieldwork into his classroom, including research he undertook in Louisiana and Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina to help homeowners determine if damage resulted from wind or water. What he wanted from QUEST was more time to learn from his fellow educators, he said.

"I've worked a lot with my kids, but I want to work more with teachers to strengthen my techniques," Jungblut said. "A person can always get stronger at what they do and this program helps very well."