Princeton University scholar Benjamin Elman has studied the history of East Asia for most of his intellectual life. Instead of getting easier, it has become more complicated — which for him is a good thing.

Elman's ongoing interest is to re-examine our understanding of China and Japan by rethinking how the history of East Asia has been told, especially in the West, but also in China, Japan and Korea.

To do so, he and other scholars are paying particular attention to the early modern period in East Asia and India — around 1600 to 1800 — to understand key developments. For Elman, this endeavor is crucial because it focuses on a time when this part of the world had advanced in many spheres, before the so-called ascendancy of Europe as an economic and political power over the course of the 19th century.

Elman, the Gordon Wu '58 Professor of Chinese Studies and professor of East Asian studies and history, argues that by shedding light on this period it is possible to have a "shift in perspective" not only regarding the history of East Asia but world history. One outcome of such a shift, Elman asserts, is that the West in particular would no longer find so "surprising" or "miraculous" the rise of China or India in the 21st century.

"What we're trying to do is change the narrative," Elman said. "It's not that it's a triumphal narrative for China, but it means in many ways that the global system is much more complicated than we thought it was. And Chinese and Indian success in the 21st century is not a miracle; it is due to longer-term economic, social and cultural developments that we need to study very carefully."

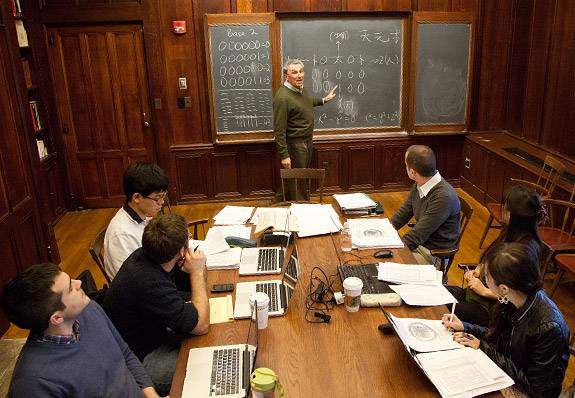

This semester, Elman is teaching a graduate class on medicine and mathematics in early modern East Asia. He is interested in showing how this part of the world had advanced in many spheres, before the so-called ascendancy of Europe as an economic and political power over the course of the 19th century. Here, Elman discusses the hexagrams in the ancient Chinese text "Yijing" ("Classic of Changes") and equates them with binary mathematics. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

In telling this story, Elman has written and edited more than 10 books, which weave together history, philosophy, literature, religion, economics, politics and science. Many of the books have been translated into Chinese as well as Korean and Japanese.

Elman, who joined the Princeton faculty in 2002, emphasizes the pronoun "we" when he talks about pursuing this work. As a teacher and a scholar, who also has been chair of the Department of East Asian Studies for the past two years and before that director of the East Asian studies program, he works closely with Princeton students and faculty members.

Elman also has been very effective in building relationships with institutions in East Asia, particularly Fudan University in Shanghai and the University of Tokyo, to establish scholarly exchanges and to expand access to archival and other research materials.

In recognition of such efforts, in 2011 Elman received the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation's Distinguished Achievement Award that honors scholars who have made significant contributions to humanistic inquiry.

"I understand the Mellon award as recognition of Ben's accomplishments in rewriting the narrative of world history, the East Asian region and Chinese history," said Stephen F. Teiser, the D.T. Suzuki Professor in Buddhist Studies and professor of religion at Princeton who directs the Program in East Asian Studies. "For nearly 35 years, Ben's scholarship has defined new trends in many domains of history."

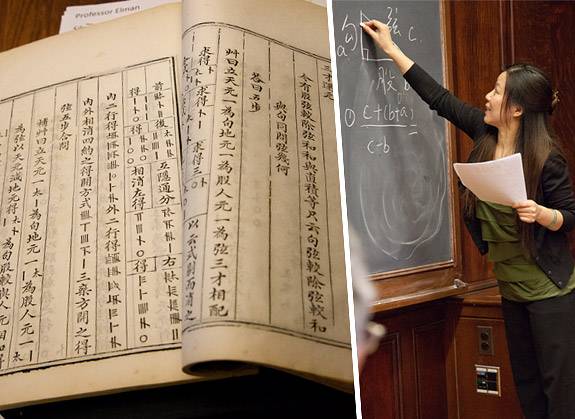

In a recent seminar, students discussed the text "The Jade Mirror of the Four Unknowns," which originally was compiled in the early 1300s and recollated and printed in the mid-1800s. Professor Minzhen Lu, a visiting fellow in East Asian studies from Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, explained the traditional Chinese matrix calculations in the text, which Elman said are akin to modern algebra from the Arab world. (Photos by Denise Applewhite)

Evolving as a historian

Elman's evolution as a scholar was by no means direct. Originally intending to study science and engineering at college, he became interested in Asian history and philosophy as a freshman at Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y. He spent his junior year in Hawaii and started studying Chinese, which he followed up with two summers in Taiwan. With no East Asian studies program yet in place at Hamilton, he majored in philosophy.

Awakening to his fascination for China, he was preparing to continue his studies in graduate school, only to have his plans disrupted by the Vietnam War; Elman elected to serve in the Peace Corps in northern Thailand.

For three years, Elman worked in malaria control, carried out epidemiology procedures along the Thai-Burmese border and learned Thai. Through training in the field, he said he "got a sense of society, economics and politics."

Upon returning to the United States, he was employed by the New York State Department of Public Health in Syracuse, where he worked in epidemiological control of venereal diseases. Again, he said, socially focused fieldwork proved to be "very good training for a historian."

During the 1970s, Elman pursued opportunities to study in Taiwan — China was off limits to Americans during this time — as well as Japan. At various times, he was employed by the U.S. State Department as a contract interpreter for guests to the United States.

In 1980, Elman completed his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. Before coming to Princeton, he taught at Colby College, Rice University and the University of California-Los Angeles, and was the Mellon Visiting Professor of Traditional Chinese History and Civilization at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Elman's Princeton colleague Susan Naquin, a professor of history and East Asian studies, has observed Elman's career over the long term. At Penn, she even served on his dissertation committee.

"Then as now, he was an intellectual powerhouse, full of ideas and fresh ways of looking at East Asia with a contagious enthusiasm for research and writing," she said.

Changing the historical framework

In working to change the historical framework in studying East Asia, Elman challenges what he calls the "failure narrative" of China. By this he means the West's "simplistic" interpretation of China as a failure economically and politically, as viewed in terms of the period from 1850 to 1950. Then, with the arrival of Maoism, the West continued to cast a dismissive — and alarmist — eye toward China, he said.

Elman uses various examples to show what, in fact, "China was doing right," noting that in many ways "the Europeans admired China in the 17th and 18th centuries because they were doing things they had not done."

He points to the civil examination system that was used for selecting government officials as one example. "I think it was a framework that the Europeans admired for selecting a government that wasn't based on aristocracies, that wasn't based on birth and that tested people based on a knowledge framework," Elman said.

Elman has been deeply engaged in developing academic partnerships between Princeton and Fudan University in Shanghai and the University of Tokyo. Here, Elman (far right, third back) was among a faculty group from the three universities gathered for a traditional Japanese dinner held at the University of Tokyo in December 2011. (Photo courtesy of Benjamin Elman)

In his book "A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China," he describes how the civil examinations— which lasted nearly three centuries before ending in 1905 — had broader outcomes in "creating through competition a literate pool of men and women" who then went on to do other things, such as becoming writers, doctors and printers.

"The consequences of this huge apparatus was that it was kind of like a gyroscope; it ordered a society in perpetual motion," Elman said. "If you failed at the exams — most did — you could do all kinds of other things as part of the cultural sphere using classical Chinese as the language of politics, society, economy, medicine, religion and the premodern sciences."

Another area of focus for Elman is the history of science and medicine in China. In his book "On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550-1900," he refutes the argument that China "had no science" and describes how the Chinese and the Europeans exchanged ideas that advanced awareness of physiology, diseases and treatments.

For example, the Chinese "had notions of circulation long before there were notions of blood circulation in the West," Elman said. "The Chinese were thinking about the flow of 'chi' (qi) and blood as one of the chi in the system."

These ideas gave rise to the practice of acupuncture, which led to an understanding of the body's organs and later was adapted to the discovery of the central nervous system in Europe. "We can now view these things with a much more positive eye instead of saying this is some backward, medical tradition," Elman said.

This semester, Elman has delved into this topic in a graduate class on medicine and the mathematical sciences in early modern Asia, which is being co-taught by Mathias Vigoroux, a postdoctoral research associate who said one of the reasons he came to Princeton was for the "great opportunity to work with a leading scholar in my field, Professor Elman."

Dan Barish, a student in the class, said, "Professor Elman, in all his work, is exceptional in his ability to allow the texts and times to speak for themselves. He gives voice to the past without the prejudice of hindsight."

Elman offers many other examples of Chinese advances in the early modern period, including the "print revolution" three centuries before Europe; the expertise in creating handicrafts from woven silk and cotton; and the prodigious production of porcelain, which required the use of specialized kilns with firing capabilities of more than 1200 degrees Celsius.

The shift in global power, he explains, occurred with the industrial revolution in Europe, when machines were built to process the raw materials coming from Asia.

"What happened was not so much that Europe had an industrial revolution, but that India and China were to a degree de-industrialized," he said. "They became sources of raw materials that were shipped to centers where they were produced in machines. What we have to see in this story is that the industrialization of Europe in many ways required the de-industrialization of China and India."

Elman noted that, "Today the epic industrialization of China brings in its wake the partial de-industrialization of the United States and Australia, for example, who both now ship massive amounts of crops and raw materials to China."

These topics are central to the courses Elman has taught at Princeton, including the freshman seminar "Global Science in Europe and China, 1600-1900"; "The Perception of China and Asia in the West"; "Culture and Society in Late Imperial China, 1000-1900"; and a range of graduate courses that explore the early modern period in China, as well as comparative history with Tokugawa Japan.

Elman's approach to reframing the study of East Asia resonates with other historians, who are eager to engage with the broader discussion.

"I am interested in discovering a new way of interpreting and describing world history," said Masashi Haneda, a professor of historical studies and the director of the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia at the University of Tokyo.

"I have learned a lot from Ben," he said. "Even when he discusses some specific topic of East Asia, he is always taking the whole world and its history into account. His discussion based on his wide view is excellent."

"Professor Elman is a globally influential scholar in the field of Chinese studies," said Zhaoguang Ge, the founding director of the National Institute for Advanced Humanistic Studies at Fudan, who is in his third and final year as a visiting Global Scholar at Princeton. "His in-depth studies focus on the history of intellectuals, civil exams and science and technologies of Ming-Qing [early modern] China. He recently has broadened his research interest into East Asia as a whole, and therefore his work now has its influence not only in the China field but also in the Japan and Korea fields."

For Jeremy Adelman, the Walter Samuel Carpenter III Professor in Spanish Civilization and Culture and professor of history at Princeton who collaborated with Elman on the first volume of the interdisciplinary history "Worlds Together, Worlds Apart," this lesson of multiplying perspectives for the interpretation of history is crucial.

"Ben insisted to all of us that world history looks distinct depending on your vantage point," Adelman said. "The view of world events looks different in Beijing than it does in London. This may seem obvious at first glance. But how do you write a book that is coherent but does not ignore the significance of perspective? Ben was so important for us for helping us figure out this puzzle. What I now teach and write about Latin American and world history has been shaped by this learning experience."

Senior Astrid Stuth said taking Elman's class "The Perception of China and Asia in the West" as a sophomore provided her with a "new framework for thinking about U.S.-China relations," and convinced her to major in East Asian studies. Stuth was named a Rhodes Scholar last year, and after she graduates she will continue her studies of China at the University of Oxford.

Internationalizing the study of history

Building a network to spark collaboration and the exchange of ideas is a vital part of Elman's work. It is also an approach that is significant in the ongoing efforts at Princeton to support internationalism as a central component of the educational experience at the University.

Adelman, who is also the director of the Council for International Teaching and Research at Princeton, said the Department of East Asian Studies "has been a model for us as we think about enhancing our presence elsewhere on the globe."

International initiatives, he said, are "important because they create opportunities for faculty and students to participate in the global production and circulation of knowledge."

Language training in Chinese, Japanese and Korean is a key activity of East Asian studies at Princeton, and undergraduates are encouraged to study in the region during their Princeton careers. Also, the intensive summer language programs Princeton in Beijing and Princeton in Ishikawa are popular for students of Chinese and Japanese.

From left: Professor Masashi Haneda of the University of Tokyo and Professor Zhaoguang Ge of Fudan University, who currently is completing his third visit to Princeton as a Global Scholar, joined Elman at the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park in Princeton in April 2011. The scholars are expanding the collaborations among the three universities to further internationalize research in East Asian studies. (Photo courtesy of Benjamin Elman)

Elman has helped forge partnerships around East Asia as well, with the multilateral relationship with Fudan University and the University of Tokyo as a central feature.

"Our partnership is triangular. That is a very important point," Haneda at Tokyo said. "Views of scholars belonging to these three institutions on East Asia and world history are often different."

Haneda said that "acknowledging other viewpoints" and "asking the reasons for these differences" allows the discussion to deepen. And, from the standpoint of Japan, he is eager to "build a bridge" that will allow for a "kind of internationalization of Japan studies in Japan."

Like Haneda, Ge said the alliance between the three universities is a "cooperation that is comprehensive and highly successful and fruitful."

Ge, who started communicating with Elman in 1996 after writing a review in China of Elman's book "From Philosophy to Philology: Social and Intellectual Aspects of Change in Late Imperial China," helped establish the institutional connection between Fudan and Princeton in 2007 when he invited Elman to join the academic council of the newly created National Institute for Advanced Humanistic Studies at Fudan. Through this relationship, Elman has pursued various research and teaching projects.

In 2009, Ge arrived at Princeton as one of the first group of Global Scholars, for one of three short-term visits over three consecutive years.

He said the experience has made him appreciate the "pursuit of excellence" of the research culture at Princeton; the value that is placed on "both the humanities and the humanistic spirit"; the "highly admired" library collections; and, in particular, the Department of East Asian Studies that is "of the highest standard worldwide."

The Princeton-Fudan-Tokyo partnership made possible a conference in December 2011 hosted by the University of Tokyo on "Local History in the Context of World History." Fudan University will host the next conference in December 2012 on "The Place of East Asia in Global History." This summer, a second special seminar for 30 chosen graduate students from the United States, Europe and China will be held in Shanghai from June 24 to July 3 at Fudan on "Studies of Asian Arts, Religion and History." A third conference is being planned at Princeton for December 2013 on "Differing Regional Perspectives of World History." Publications in English and Chinese will capture the work coming out of these discussions.

The institutional partnerships also have generated academic opportunities for students. Elman said that over the past five years, one or two Princeton graduate students a year have gone to Tokyo or Fudan to pursue research.

For Victoria Lee, a Princeton Ph.D. candidate in the history of East Asian science currently pursuing research at the University of Tokyo, the access to archival as well as secondary literature is essential to her work. Further, she said, "Engaging with Japanese scholars has provided a valuable perspective on my topics of study, in addition to giving me familiarity with the Japanese academic system."

Producing concrete results out of scholarly debate is an important goal for Elman, and the Mellon award is helping him organize new avenues for collaboration. In early May, he convened workshops at Princeton that will lead to a series of publications offering a comparative framework on historical developments in China and India in early modern times.

This project has also been sponsored as a research cluster jointly funded by the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies and the Program in East Asian Studies since 2009, which included parallel meetings on artisans, work and material culture in early modern China, organized by Naquin.

Another Mellon grantee, Sheldon Pollock, the Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies at Columbia University, is involved in this endeavor. "Our thinking about the India/China project is still very much in the planning stages, but Ben and I, and our other collaborators, understand the need to produce a book for the general reader about the lineages — social, political, ecological, intellectual, aesthetic — of these two re-emergent powers," he said.

"Truly globalized learning begins to take place when we have a steady, working relationship with our colleagues abroad," said Teiser, who will be teaching at the seminar at Fudan this summer.

Looking ahead, Elman and his colleagues at Princeton and beyond envision new opportunities for teaching, research and collaboration that will serve to internationalize the study of history.

"I think that in the future we will have scholars globally doing world history together," Elman said. "We need to undo the earlier narratives and to see things as they were dynamically developing from the inside, rather than seeing them passively from the outside in hindsight."

A poster promotes a conference between Fudan, Princeton and Tokyo universities held in Shanghai in December 2011 on "Local History in the Context of World History." The conference was the first in a series to be held annually. (Image courtesy of Benjamin Elman)