Strolling through the Princeton University Art Museum, a visitor readily notices the resemblance: The elongated man's head in a 20th-century Italian painting is shaped exactly like a nearby decorated weaving loom pulley from 19th-century West Africa.

It is no coincidence that these pieces resonate visually with each other — or that they are now displayed together in the art museum. It is part of a new approach the museum is taking to showcase its 72,000 objects, intended to make the collections more accessible to patrons by drawing connections and providing additional context and background.

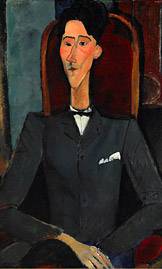

African art, such as the decorated loom pulleys (above) from 19th-century West Africa, inspired many artists working in Paris in the early 20th century, including Modigliani. Caroline Harris, curator for educational and academic programs at the museum, said that Modigliani's work "shows the translation into his painting of the aesthetics" of the African pulleys. Referring to his painting "Jean Cocteau," (above right) she added, "… when you look at the treatment of the face — the way that the eyebrow is related to the nose, the elongation of the face and the chin, and the somewhat diamond-shaped mouth — all of those stylizations of the features really resonate with the African objects." (Video still by Nick Barberio)

The museum recently reinstalled its galleries of European and American art from the medieval period to the present. These 13 galleries now bring together well-known favorites with new acquisitions and mix works across media, as shown in the accompanying video. The technique enables the museum to draw on the depths of its holdings to tell richer and fresher stories.

"We wanted to create new opportunities to rotate works through the collections galleries on a more regular basis and to somehow break down the boundaries between different areas of the collections," said James Steward, who has championed the new method since joining the museum as its director in 2009.

"For pragmatic reasons, we thought it would be interesting to create some new juxtapositions across collections, across cultures," he continued. "Intellectually, it felt to us that this would bring our practice as a museum much more in line with what has been happening in the broader academy for the last 20 or more years: crossing disciplinary borders more regularly, looking to find the connection between and through disciplines, and to speak to points of cultural contact."

For example, in one gallery some paintings by 20th-century Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani are shown near a case containing several 19th-century heddle pulleys, which resemble small portrait masks, from weaving looms of the Baule and Guro people from what is now the Ivory Coast.

Caroline Harris, curator for educational and academic programs at the museum, said that Modigliani was heavily influenced — like many artists working in Paris in the early 20th century — by African art. She points, in particular, to a portrait on display of poet, playwright and future filmmaker Jean Cocteau by Modigliani.

"It shows the translation into his painting of the aesthetics of African sculpture," she said. "It's lovely that we have these heddle pulleys in association with the Modigliani because this is exactly the sort of African art that he was looking at and was interested in. And when you look at the treatment of the face — the way that the eyebrow is related to the nose, the elongation of the face and the chin, and the somewhat diamond-shaped mouth — all of those stylizations of the features really resonate with the African objects."

Non-Western art forms, such as Ando Hiroshige's Japanese woodblock print, "100 Views of Edo," (left), were used by many avant-garde artists of the late 19th century, including Vincent van Gogh, for innovative approaches to composition and color. Van Gogh's oil painting, "Tarascon Diligence, "(Tarascon Stage Coach), is shown on the right. (Photo of the Hiroshige print courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum; photo of the van Gogh painting by Bruce M. White)

Steward said that the goal of the new way of displaying objects is to answer fundamental questions about works of art.

"There's been a concept based on what (art historian) Michael Baxandall called 'the period eye' — a sense that through looking at a broad array of what's called 'cultural artifacts,' we can get a better understanding of the impulses of a culture at any given point in the past, and therefore pull objects out of a vacuum and put them in a broader context," he said. "That is something that has been at large in the broad fields of the humanities for a good while now, but not something that we've particularly explored relative to our installation practice in the museum galleries until very recently."

The approach provides opportunities to incorporate much more interpretive information in the galleries, such as more complete labels addressing "the question of why an individual work of art matters — why someone who isn't a specialist in the discipline ought to find something engaging," according to Steward.

In one gallery, the 1888 painting, "Tarascon Diligence, "(Tarascon Stage Coach) by Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh is displayed near two 1856-57 Japanese woodblock prints from the series "100 Views of Edo" by Ando Hiroshige. A nearby label explains that many avant-garde artists of the late 19th century abandoned traditional European painting practices and looked to non-Western art forms, such as Japanese prints, for innovative approaches to composition and color.

Christopher Heuer, an assistant professor of art and archaeology at Princeton, said that the new approach is going beyond making the museum more accessible to patrons.

"(It) will do what museums across the country, across the world are being forced to do now, which is make art relevant to the present day in a way that's more than kind of superficial," Heuer said. "That's always been something we try to talk to students about, but James has also been crucial in opening up the museum to more than just the University community. These kind of comparisons he's drawn are just one way to do that."

Steward said he wants the museum to serve students of art and of other disciplines, and members of the University community and the wider community. He has implemented several initiatives designed to make the museum more approachable, including keeping the galleries open Thursdays until 10 p.m. and programming those evenings with other activities connected with the visual arts, such as film screenings, gallery talks and concerts.

"I think increasingly our mission is to serve simultaneously as a very deep and rich 'laboratory' for teaching and research that goes back to 1882 when we were co-founded with the Department of Art and Archaeology, but recognizing that we can't any longer simply be a 'laboratory' for that finite sub-part of the University community," Steward said. "Instead, we have to engage every Princeton student. My view is that once we're embarked on that goal of trying to find ways, whether they're in the classroom, outside the classroom or on a purely social level, we're developing strategies that are just as likely to be effective in finding ways to engage members of the non-University public."

The museum recently received a $500,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation of New York to support an expansion of this effort, called "Activating the Collections." The award will fund, in part, the establishment of a new position, a curatorial fellow for collections engagement, who will work with curators, faculty, students, guest scholars, artists and other experts across disciplines to develop and present compelling interpretative approaches and materials.

The grant also will establish the Museum Voices Colloquium, which will function as a visual arts think tank in bringing together traditional and nontraditional experts to consider new ways of understanding art.

"Jean Cocteau" and "Tarascon Diligence" are on long-term loan from the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation; "100 Views of Edo" is a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Straka; African heddle pulleys are from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Brian Leyden.