Even as July 4 is recognized nationwide for the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the date has additional significance for the town of Princeton, which made history on that same date seven years later.

On July 4, 1783, the town received a letter from the president of the Continental Congress confirming that Princeton would be the home of the U.S. government in the waning months of the American Revolutionary War.

The fact that Nassau Hall, the oldest building of present-day Princeton University, was the home of the Continental Congress is an oft-cited part of Princeton history, but the events that transpired to make it happen are less well known.

In the book "The Continental Congress at Princeton" (1908), author Varnum Lansing Collins presents a letter that Elias Boudinot IV, 10th president of the Continental Congress, wrote to the town of Princeton on July 4, 1783.

"I am honored by the commands of Congress to signify to you their acceptance of the use of any of your Buildings that may be indispensably necessary for public offices; and to express their high sense of your kind offers of service and attention to their accommodation and convenience," wrote Boudinot, who also served as trustee of the University -- then known as the College of New Jersey -- from 1772 to 1821.

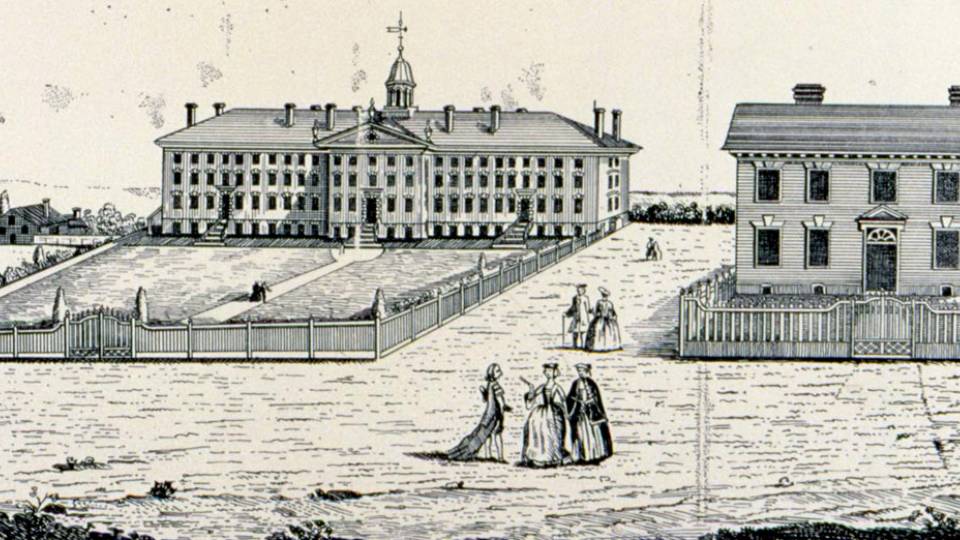

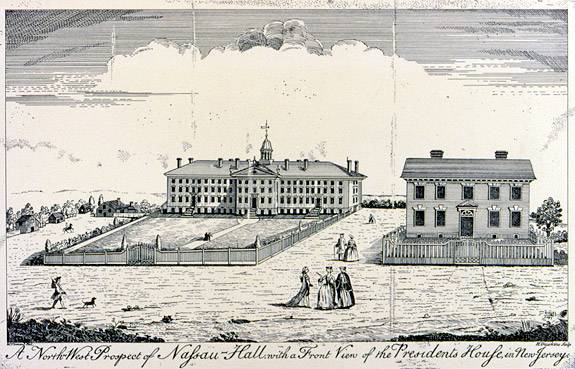

This 1764 copper engraving by Philadelphia artist Henry Dawkins -- copied from a drawing by William Tennent, a 1758 alumnus -- shows Nassau Hall (at left) as it likely looked in 1783, when the Continental Congress called Princeton home beginning in July of that year. To the right is Maclean House, which was the home of the president of the college, then known as the College of New Jersey. Maclean House still stands today as home to Princeton's Office of the Alumni Association. (Image courtesy of Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections)

Just two weeks earlier, the capital of the country was in Philadelphia, but Collins' historical account shows that thoughts of Princeton were simmering there as the tempers of Continental Army soldiers were flaring.

Congress adjourned on the afternoon of Friday, June 20, 1783, "as was their custom," but Philadelphia was in a state of unrest as soldiers described as "mutineers" had been gathering in the city for days to demand back pay for their service during the war.

Members of Congress, most notably Boudinot, who was a native of New Jersey, felt that the situation had grown critical by the night of June 20.

"The air was alive with wild rumors," Collins wrote. "Some said that the mutineers intended to raid the bank; others declared that an assault would be made on the Council; others that Congress was to be seized and held for ransom … ."

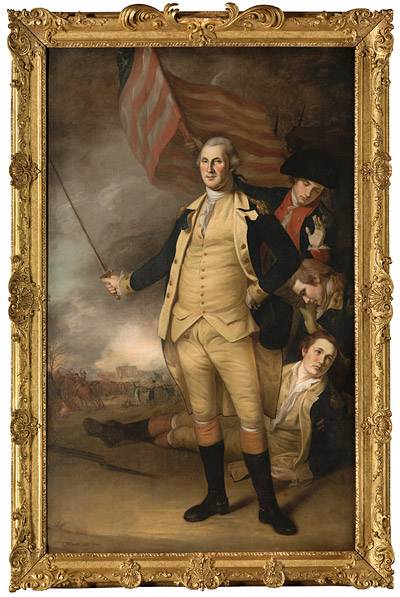

Gen. George Washington was among the dignitaries who visited Nassau Hall -- seen here in the distance -- while the Continental Congress was in session in Princeton from July to November of 1783. The general is said to have contributed 50 guineas to support the college, and the trustees responded by requesting that he sit for this portrait, "George Washington at the Battle of Princeton" (1784) by Charles Willson Peale, which remains in the University's collection. (Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum; Photo by Bruce White)

The congressional committee demanded from the president of the state council of Pennsylvania some action to confront the soldiers and deal with the issue of pay. Multiple emergency sessions of state and congressional representatives were called over that weekend, and Boudinot dispatched a letter to Gen. George Washington asking for troops to quell the soldiers.

At 11 p.m. June 21, Boudinot wrote a second letter to Washington in which he sent three resolutions, one of which resolved "to summon the members of Congress to meet on Thursday next at Trenton or Princeton in New-Jersey in order that further & more effectual measures be taken for suppressing the Present revolt & maintaining the dignity and authority of the United States."

According to Collins, the state recognized that the citizens of Philadelphia were sympathetic to the concerns of the soldiers, and decided not to call out the militia against them. John Dickinson, president of the Pennsylvania state council, felt he could do nothing other than to "advise Mr. Boudinot to adjourn from the City."

Word made its way to Boudinot, and on June 23, 1783, he wrote to his brother, Elisha, in New Jersey, "Congress will not sit here, but have authorized me to change their place of Residence -- I mean to adjourn to Princeton if the Inhabitants of New Jersey will protect us … ."

On June 24, Boudinot set off for Princeton after issuing the Proclamation Adjourning Congress to Princeton. In the proclamation he called for all the delegates to meet in Princeton June 26.

The town of Princeton's loyalty during the Revolutionary War that raged close to home -- as seen in this painting, "Washington Rallying the Americans at the Battle of Princeton" (1848) by William T. Ranney -- was possibly a factor in the Continental Congress' decision to move to Princeton in 1783, according to historians. (Courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum; Photo by Bruce White)

Personal ties bring Congress to Princeton

While historical records don't document the reasons why Boudinot chose Princeton over Trenton, Collins wrote that it was not the first time that members of Congress had considered Princeton as home to the federal government. Correspondence of 1779 shows at least one member of Congress referred to buying land in Princeton to establish public buildings for a permanent home for the federal government.

But historical accounts more or less deduced that Boudinot's reasons were personal. He knew Princeton well.

"As a boy he had played along its fertile street when his father's silversmith shop was also the village post office," Collins wrote. Boudinot had married Hannah Stockton, who was the sister of "Princeton's leading citizen," Richard Stockton, who had been a member of Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

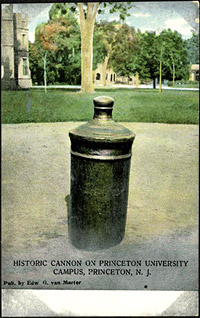

This historic postcard, "Historic cannon on Princeton University campus, Princeton, N.J." (circa 1900-1960), shows the cannon that remains muzzle-down in the center of Cannon Green behind Nassau Hall. Among other artifacts of the American Revolutionary War era on the Princeton campus, it was abandoned by the British Army after the Battle of Princeton in 1777. (Image courtesy of Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections)

There was also the fact that Boudinot's colleague John Witherspoon had left Congress a few months earlier to become president of the College of New Jersey. He was president from 1768 to 1794.

"Nor is it possible that as a trustee of the College of New Jersey he (Boudinot) had forgotten its unswerving loyalty to the Revolutionary cause or lost sight of the patriotism of citizens whose little village rejoiced in a well-earned reputation as a hot-bed of rebellion," Collins wrote.

The New Jersey State Council welcomed the Congress unanimously, submitting a letter pledging the loyalty of the state.

Vice President of the College Samuel Stanhope Smith also presented to Congress a letter June 26, 1783, on behalf of the governors and masters of the University offering, "If the Hall, or library room, can be made of any service to Congress, as places in which to hold their Sessions, or for any other purpose, we pray that they would accept them during their continuance in this place."

The Congress passed a resolution July 2 accepting the use of Nassau Hall, sent a letter to the town July 4, and the University was the seat of the federal government from July to November of 1783.

It was while in Princeton that the Congress learned that the Treaty of Paris had been signed Sept. 3, 1783, and it was this peace treaty that ultimately recognized the nation's independence.