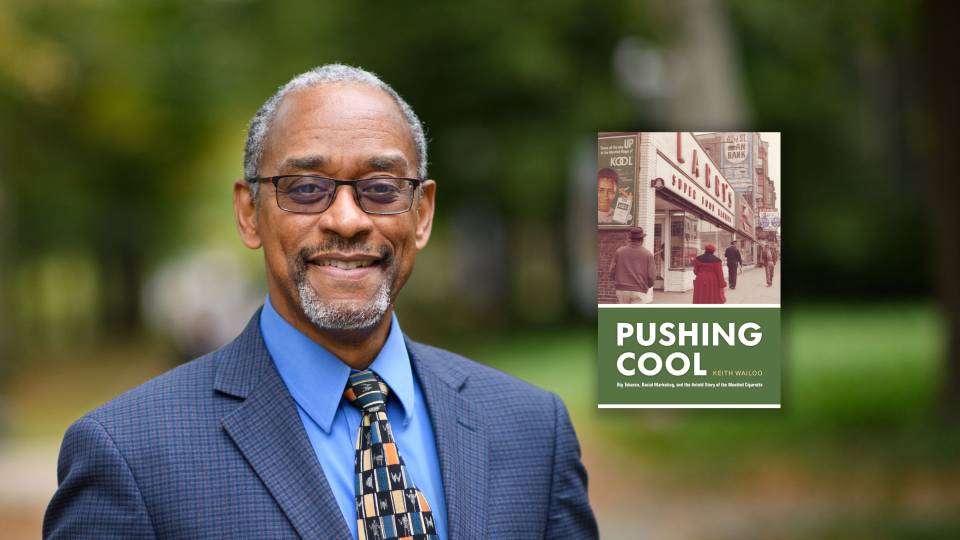

In investigating public health issues, Princeton University scholar Keith Wailoo assumes an array of roles: historian, scientist, anthropologist, sociologist and policy analyst.

He looks at cancer through the lens of race and gender in his new book, showing how a disease once believed to afflict mainly wealthy white women was transformed in the scientific, medical and public imagination. In his undergraduate course on drugs in America, he illuminates how legislation on narcotics such as opium and crack cocaine was tied to attitudes about racial and ethnic groups associated with their use.

This multifaceted approach has brought Wailoo -- a professor in the Department of History and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs -- to the forefront of the study of the history of science and medicine. His research and teaching tackle issues at the nexus of health and society, with particular attention to race and identity.

"I've always been drawn to study science and technology as a way of understanding issues of progress, conflict and the impact of new knowledge on society," Wailoo said. "As a historian, I've also been fascinated by the intended and unintended implications of scientific and technological and medical innovation."

Angela Creager, a Princeton professor of history who, along with Wailoo, is an executive committee member of Princeton's Program in History of Science, said, "What I admire about Keith's work is that he is able to bring together analysis of technological developments in medicine with the history of social perceptions, showing how the social and technical sides of medical change are closely related, often in unexpected ways. His work in the history of science and medicine on race and medical research absolutely leads the field."

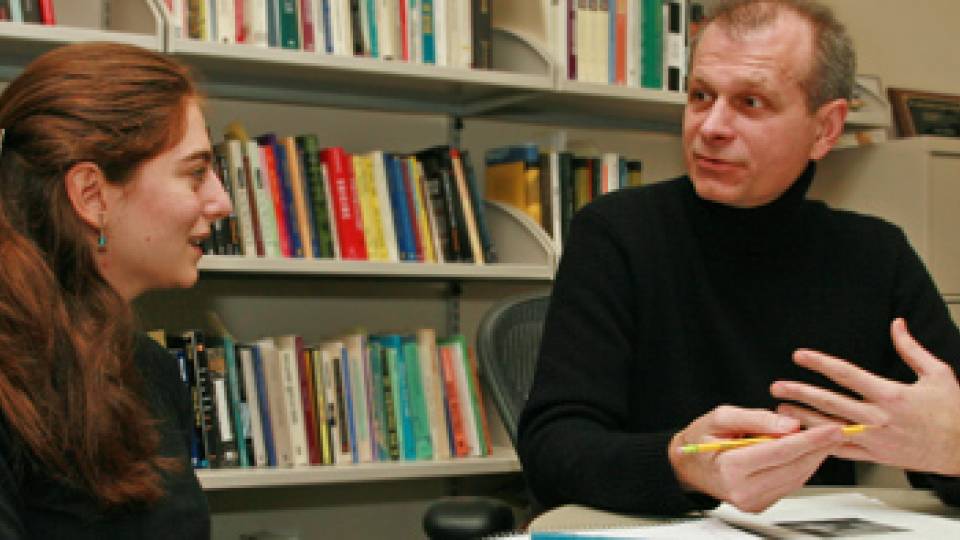

Wailoo leads a precept discussion for his class "Race, Drugs and Drug Policy in America," which examines drug policies and their relationships to debates over immigration, identity, cultural and biological differences, and criminality. (Photo by Brian Wilson)

Wailoo joined the Princeton faculty in 2010 as the Townsend Martin Professor of History and Public Affairs after spending the previous year as a visiting fellow in the University's Center for African American Studies. Previously he taught at Rutgers University, where he founded the Center for Race and Ethnicity, and at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, where he taught in the history department and the medical school.

In recognition of his work in bringing history to bear on health policy, Wailoo in 2007 was elected to the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies -- an independent nonprofit that works to educate decision-makers and the public -- and serves on the institute's health sciences policy board.

Moving to Princeton has enabled Wailoo to forge new relationships with scholars and students who share his multidisciplinary interests. This past spring, for example, he taught a graduate course in the Wilson School on "Controversies in Health Policy," covering subjects such as direct-to-consumer advertising, end-of-life care, the role of the courts in health care reform and the history of Medicare.

"The students were a diverse group made up of physicians, students with policy experience, others with law degrees and heading to clerkships, some with science backgrounds and others who are going off to study political science after completing the public policy degree," Wailoo said. "It's an ideal setting for teaching and learning. What linked us was a common interest in the complex and sometimes perverse pathways by which health policies evolve, and an interest in how the past has both constrained and created opportunities for reform in the present."

More broadly, Princeton "is a perfect place for me to be in that it makes good use of all of the approaches I have developed in terms of my teaching and research," he added. "It is an exceptionally stimulating environment drawing me into sustained interaction with leading figures in history and policy."

From science student to journalist to professor

Wailoo began to amass his diverse scholarly interests as an undergraduate at Yale University, where he was a chemical engineering major but also was fascinated with philosophy and history, and developed a deep love of writing.

After graduating from Yale in 1984, he worked as a freelance writer for American Scientist magazine, scientific research organizations and Yale Alumni Magazine. He then decided to pursue a Ph.D. in the history and sociology of science from the University of Pennsylvania, which he earned in 1992.

"As a freelancer I found myself living hand-to-mouth. It struck me that having a Ph.D. would provide a stable basis for having a writing career, which has turned out to be true," he said with a laugh. "Little did I know that I would love being a professor and thrive with the kinds of engagement that teaching brings. But, truth be told, I still think of myself primarily as a writer."

Wailoo's output as a writer and editor has been prolific and he has received numerous awards for his books, most notably "Dying in the City of the Blues: Sickle Cell Anemia and the Politics of Race and Health" (2001). Set in the city of Memphis, the book examines the history of sickle cell anemia's association with African Americans and the sociological factors that affected the diagnosis and treatment -- or lack thereof -- of the disease in black patients.

"Dying in the City of the Blues" is "probably his most famous contribution to the literature -- a truly spectacular book," Creager said.

Wailoo's other award-winning books include "The Troubled Dream of Genetic Medicine: Ethnicity and Innovation in Tay-Sachs, Cystic Fibrosis, Sickle Cell Disease" (2006) and "Drawing Blood: Technology and Disease Identity in 20th-century America" (1997). He currently is completing a study of the politics of pain medicine. He also has co-edited books on transplantation and immigration; the impact of Hurricane Katrina; and genetics, race and history.

"Keith never starts from a polemic position when investigating the social forces shaping the science and practice of medicine," said Carolyn Rouse, a Princeton professor of anthropology who also studies medicine and social inequality. "Particularly in the case of race and gender, Keith investigates medical mistakes, statistical uncertainties and treatment disparities as the outcome of discourses and genealogies that cause us to confuse opinions and emotions with fact."

In his newest book, "How Cancer Crossed the Color Line" (2011), Wailoo traces the history of cancer diagnosis, treatment and awareness over the past century, from a time when it was seen as a disease largely affecting well-to-do white women.

"In a world where the poor were more likely to die younger of infectious disease, the mantra then was that you were lucky to live long enough to get cancer," Wailoo said. "So for people who were better off and had higher expectations of longevity, there were higher rates of cancer. And given the diagnostic tools that were available 100 years ago, cancers of the breast and cervix -- which were the main killers of women -- were far more likely to be diagnosed."

At that time, cancer diagnoses also were more likely to be made by urban doctors, so whites were overrepresented among cancer patients compared to African Americans, who lived predominantly in the rural South, Wailoo noted.

"At the birth of cancer awareness, the malady was not seen as an equal opportunity disease, and the story I tell is of how that perception took shape and changed over the course of 100 years and is still changing," said Wailoo, who cites the 1979 death of popular soul singer Minnie Riperton from breast cancer as a seminal moment in raising cancer awareness among African Americans.

The book is an example of what Rouse calls Wailoo's greatest strengths: "his brilliant questions, meticulous research and historical prose."

Addressing controversies in the classroom

As with his research, Wailoo brings a curiosity about wide-ranging medical, scientific, social and policy issues into the classroom. As a visiting professor at Princeton he taught a course on "Race, Drugs and Drug Policy in America" in spring 2010, drawing positive reviews from among the 60 students who enrolled. In spring 2011, the course attracted more than 120 students.

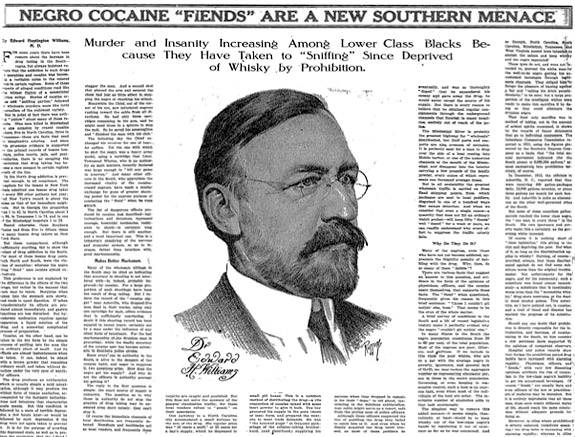

The course explores how controversial substances become the subject of debates over immigration, identity, cultural and biological differences, criminality and other issues. Ranging from the Colonial era to the present, Wailoo and his students discuss controversies that swirled around opium and Chinese immigration, the impact of Prohibition on today's drug policies, differences in sentencing patterns for crack and powder cocaine convictions, and the interaction of drugs, youth rebellion and social change.

In his undergraduate course on drugs and America's drug policy, Wailoo investigates controversies about narcotics legislation that are fueled by attitudes about certain racial and ethnic groups. Wailoo and his students review how these attitudes were reflected in historical images, newspaper and magazine articles, and video clips, such as this 1914 New York Times column allegedly about cocaine use.

"I'm fascinated with the ongoing set of debates about how to define the line between permissible and impermissible drugs -- from medical marijuana to Ritalin -- and how that line shifts over time, and what it tells us about the role of government in determining health care choices and options," Wailoo said. "Controversies about drugs are never only about the drugs -- they're also about social norms and values, and evolving ideas about the users themselves."

Colin Quinn, a member of the class of 2012 who took the course this spring, said Wailoo helped students "understand the different time frames and points of view that we were studying. He also seemed to genuinely care about student input. He would pose a question at the end of every lecture and then post a few of the most insightful student responses to start off the next lecture's Powerpoint, which allowed us to consider varying perspectives."

Quinn, a Wilson School major, said students learned that, in terms of understanding the genesis of drug policies, "often it's not what any drug does, but rather who is using it. True or not, it is very easy for certain perceptions to form around certain drugs. It was also interesting to examine the government's role in shaping perceptions."

Justene Hill, a graduate student in history who served as a preceptor for the course, said Wailoo succeeded in the "herculean task" of giving the students a nuanced understanding of drugs in American society. "He is a master lecturer, using images, newspaper/magazine articles, video clips and popular cultural references to convey sometimes complex information about drugs and policy," she said.

Tomiko Ballantyne, a graduate student in history and preceptor for the course, added, "As a scholar, Professor Wailoo's entire process is inspiring for me. His work ethic is undeniable but, aside from that, he is able to use the richest historical details one can possibly find to build meaningful, teachable narratives. In that way, Professor Wailoo is everything a great historian should be. He mentors his students, he provides great leadership for his preceptors and his lectures are full, exciting one-hour journeys."

In the fall, Wailoo will teach a Wilson School junior policy task force titled "To Medicate or Not? Children and Drug Policy," which will analyze trends and policy dilemmas in medicating youth for conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disabilities and bipolar disorder. Students will produce recommendations for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the New Jersey Department of Youth and Family Services.

"I want students to understand the multiple ways in which the thing we call public policy takes shape," Wailoo said. For policy students, in particular, "my goal is to help them understand not just the history of those discussions but the stakes involved, their implications for patients and people who suffer from illnesses, and also to look ahead to anticipate the consequences of the kinds of policy developments which they presumably will be part of making."