Name: Gyan Prakash

Title: Dayton-Stockton Professor of History

Scholarly focus: Modern South Asia, urban history and postcolonial studies. He is the author of "Mumbai Fables," "Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India" and "Bonded Histories: Genealogies of Labor Servitude in Colonial India."

Published this fall by Princeton University Press, "Mumbai Fables" tells the story of this great Indian city, which before 1995 had the colonial name of Bombay. What inspired you to write the book?

An obsession. Since childhood, I have been obsessed with the city, though it is not my hometown. I grew up in a town nearly a thousand miles away from Mumbai, or Bombay as it was then known. Bombay was never just another big city, but an idea, a figure of myth and desire. Cinema, newspapers, magazines, novels and visiting relatives all stoked this desire. After I completed my last book, "Another Reason," which was on the cultural authority of science in India, I decided to return to this lifelong obsession. I spent four months in Mumbai about 10 years ago, trying to figure out how to approach it, how to understand the origins and the history of Mumbai’s imaginary life. What lay behind it? What were the historical forces that produced these images? I hit the streets, walked the lanes and bylanes, talked to anyone who would talk to me, scoured archives and libraries, and read everything I could find written on Mumbai. "Mumbai Fables" is the result.

Published in 2010 by Princeton University Press, "Mumbai Fables" was written by Prakash during his 2008-09 sabbatical year that he spent in Mumbai, where he said he "negotiated the routine challenges as well as the pleasures of everyday life." (Photo of book cover by Brian Wilson)

What is your relationship to Mumbai?

I have always had a relationship to the idea of Mumbai. Ten years after I began my research, and even after writing the book, I still find the city's myths compelling -- all the more so because I now understand them and am better able to appreciate their rich texture. This has made my relationship to the city more intense. My wife and I even bought an apartment in the city because I wanted to get a sense of what it was like to deal with it on a daily basis, to negotiate the routine challenges as well as pleasures of everyday life. I wrote the book in Mumbai during my 2008-09 sabbatical year. I wanted the book to have the feel of having been written in daily engagement with the city.

You are a historian who looks at the story of Mumbai through many lenses -- politics, architecture, literature, art, film, criminal trials and even comic strips. Why do you employ so many viewpoints and what was your process for writing the book?

As I researched the city, I became convinced that Mumbai's various lives -- artistic, literary, political, economic and legal -- spilled into each other. No domain was self-contained. People lived the map of the city revealed in the newspapers and tabloids. Street life borrowed from cinema as much as the screen drew from real life. I saw architectural plans not just as lines on paper, but also as dream texts. Court trials drew from theater, and cinema placed the law on trial in its narratives. All this cross-pollination required that my research had to identify lateral links between different materials even as I traced their respective linear histories. I looked for relationships between archival documents, newspaper accounts, literary materials, cinematic representations, political treatises and architectural design. This made the research very demanding but also great fun.

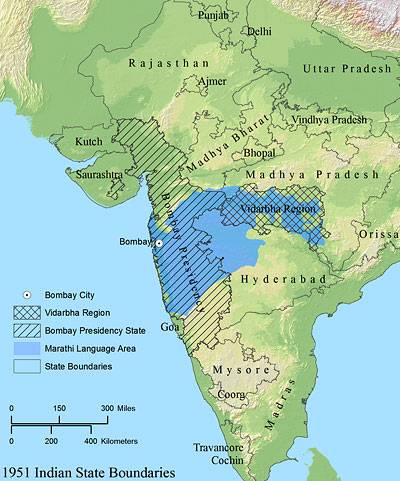

Having the colonial name Bombay before 1995, Mumbai, says Prakash, is fabled as a unique Indian city "where anything is possible, where you can create something out of nothing." (Map illustration by Tsering Wangyal Shawa)

You describe Mumbai as a "triumph of human artifice." Why is that? What makes it so unique?

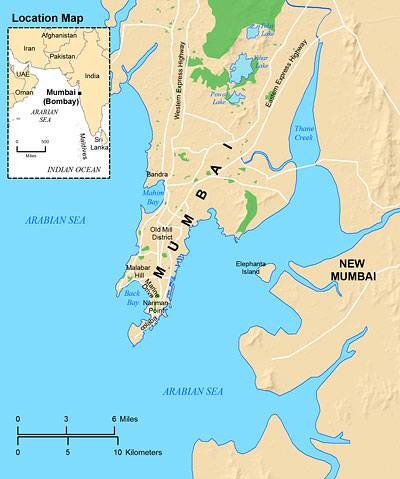

Of all the cities in India, Mumbai is thought to be one place where anything is possible, where you can create something out of nothing. This is part of the city’s historical DNA. Consider its origins. When the Portuguese seized it, Mumbai was one of seven islets on the Arabian Sea. Not until the 19th century were the breaches filled and the seven islets joined to become a single island city. Under British rule, hundreds of thousands from India and beyond washed up on its shores, attracted by its promise. Under discriminatory conditions, Indian merchants and traders built thriving enterprises, and poor immigrants worked in its cotton mills and built the city, enduring incredibly oppressive and exploitative conditions. It is this history of survival and growth amidst tremendous odds -- in both the colonial and postcolonial periods -- that makes Mumbai a place for the triumph of human artifice.

You say that your "desire" and "hunger" for Mumbai grew out of images of the city, both real and imaginary. For you today, what might be most "real" about this city, and what is "imaginary?"

I don't draw strict lines between the "real" and the "imaginary" because I believe that we experience one in the other. We live our imaginations. Even something as "real" as daily commuting in the Mumbai trains is shaped by the images we draw of its crowded compartments, the little tricks of the trade that commuters use to negotiate the crowds, the images we carry in our heads of the train stations.

Doing research in Mumbai, Prakash made connections between materials from literature, architecture, history, cinema, politics, law and the media. (Photo by Aruna Prakash)

In the media in Mumbai you say there is a lot of talk about the "death of the city" -- that its glory days are behind it due to its ever-expanding population, the vast gap between rich and poor, and ongoing traumas such as natural disasters and violence. What is your view of the future of Mumbai?

I regard the talk about the death of the city as critical comments on the challenges of current urban life. To be sure, Mumbai today is not what it was four decades ago, and it is true that its current urban form is that of a megalopolis and not a classic city. But this only means that the challenges are different today. They are more formidable than they were earlier. Mumbai's problems are caused by growth and dynamism, not decay and stagnation. Yes, urban violence, poverty, environmental degradation and many other such problems are intense. But Mumbai's residents have tremendous survival skills, and there are many thoughtful urban activists who continue to struggle for a better future.

Mumbai has a huge film industry -- Bollywood -- in which you seem to be playing a major role. What is that role and what is it like to be part of this larger-than-life endeavor?

You cannot write on the city, engage with its imaginative life, and not encounter the film industry. And I did. While doing my research I came to know a number of people in Bollywood, many of whom became dear friends. It also turned out that my research material lent itself to cinematic storytelling. So, encouraged by a friend, I wrote a dark story. A film director, Anurag Kashyap, liked it. So I went on to write a script, about which I knew next to nothing. I wrote version after version -- nearly 15 before I could come up with something that was acceptable. The director loved the idea, and so did a production company. It has been a great learning experience, but I don't seek a major role in the film industry. I like my day job at Princeton! [The film, titled "Bombay Velvet," will be in production later this year.]

Do you bring your tales of Mumbai back to the Princeton classroom? How does this material inform your teaching?

Always. In my graduate seminar on modern cities, I always draw on my research on Mumbai. Anecdotes, books, current events and historical episodes -- I bring them all in. These often help to clarify what is unique to Mumbai, while shedding light on other urban experiences. I tell my students to stop me if I go on and on about Mumbai. They are very indulgent, and appreciate my enthusiasm. I think enthusiasm for your subject has good pedagogic value.

Formed by joining seven islets in the Arabian Sea, Mumbai today is a cosmopolitan metropolis that Prakash describes as "a city of immigrants that was sired by colonial conquest." (Map illustration by Tsering Wangyal Shawa)