For nine days, Sarina Meikle wrestled with the question of how to get a crucial genetic test to work.

Was her solution too diluted? Were the temperature settings she needed to establish in multiple stages for this polymerase chain reaction technique too high? Too low? Meikle, a rising senior in molecular biology at Princeton, thought that perhaps the problem rested with her primers, which are the short fragments of DNA activating this technique that amplifies pieces of genetic material.

Meikle applied the research techniques she is refining as one of 99 undergraduates from Princeton and other U.S. colleges participating this year in the University's Summer Undergraduate Research Program in Molecular and Qualitative and Computational Biology. She checked and re-checked her materials, her procedures, her thought processes.

On the 10th day of her research, the test worked after she reset some temperature ranges. "Finally, success!" Meikle said, beaming hours after her victory, now knowing that she could move along with her experiment. "We just kept on trying different things."

Princeton undergraduate Sarina Meikle (right), met often with molecular biologist Alison Gammie in strategy sessions on her summer research project. (Photo: Denise Applewhite)

In being challenged in this way, Meikle and other students in the summer biology program are learning one of the truths of cutting-edge research -- that practitioners of research are trailblazers, forging new paths through unforeseen obstacles, technical and otherwise. Research by its very nature, its adherents say, requires a certain toughness of mind.

"What separates those who are going to be scientists from others is the willingness to persevere and face discouraging results and get the energy up to do something different," said Alison Gammie, a Princeton molecular biologist and the program's director since 1999.

The program, funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Princeton's Department of Molecular Biology and Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, the Genentech Foundation, and the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research, supports intensive laboratory research experiences for a select group of undergraduates chosen from a nationwide pool.

Each student is assigned to a research group headed by a Princeton faculty member, and carries out an original research project. Students visiting from other universities work in campus labs for nine weeks. Princeton students also complete nine weeks but continue their investigations into the academic year.

Meikle is working in Gammie's lab this summer and will continue through the coming year, writing her thesis on her research. Gammie studies a genetic process called DNA mismatch repair, which protects organisms against genetic mutations that often can lead to cancer. Meikle is studying the process in yeast and investigating what carcinogens prompt mutations in copies of this protective gene.

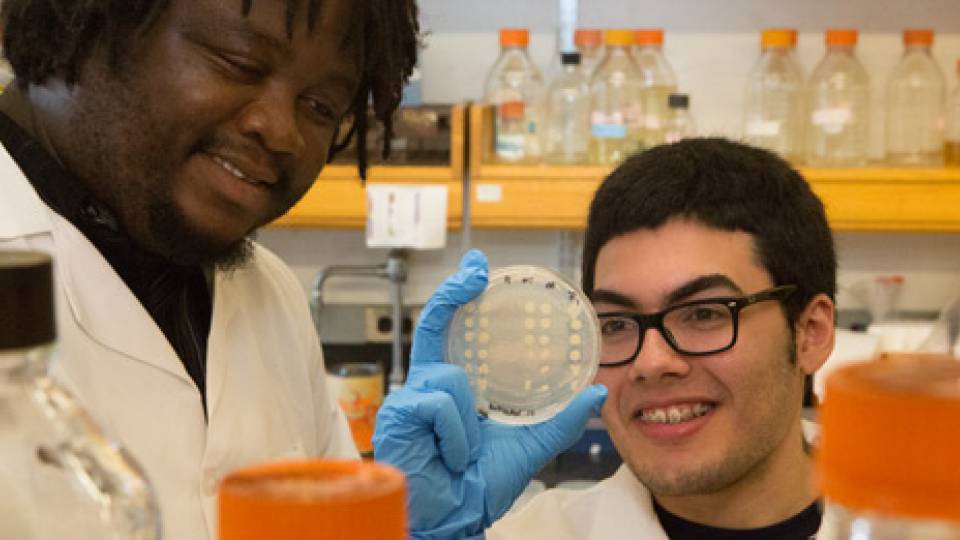

The nine-week program culminates in a mass poster presentation allowing students to explain their research projects to the University community. Students in the program also immerse themselves in the campus' scientific culture, collaborating with other undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and faculty. (Photo: Brian Wilson)

Separately, Meikle also is studying broad genetic patterns within these mutated genes.

Gammie, a senior lecturer in molecular biology, explained that in designing research assignments for students, "you want it to be real." She added, "You want the students to be part of something that is new and exciting, a real project that they can be enthusiastic about -- we don't want to give them something pedestrian."

Students in the program also immerse themselves in the campus' scientific culture, collaborating with other undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and faculty. In ongoing discussion groups, they learn how to analyze and present data. They attend weekly seminars given by Princeton faculty and also career forums where they interact with former program participants. The nine-week program culminates in a mass poster presentation allowing students to present research to the University community.

More than 70 percent of former participants have gone on to pursue doctoral degrees, medical degrees and programs combining those degrees, Gammie said.

Being inspired to pursue research

On a 100-degree July afternoon, about 70 students in the summer program poured into a cool basement auditorium in Thomas Laboratory for a talk by the noted Princeton molecular biologist Bonnie Bassler, titled "Tiny Conspiracies -- Cell to Cell Communication in Bacteria."

Bassler spoke about her work, tracing the history of an idea -- quorum sensing, which involves how bacteria communicate with each other -- how she made her discoveries concerning the phenomenon, and what it means. Along the way, she interjected humor and commentary, which kept the crowd smiling. "Oh wait, this is science, this is serious," she said, getting more laughs. Her research, she said, explains why bacteria, which are so tiny, are so successful as organisms. They do more than just eat and sleep, she contended. "They talk to one other and carry out tasks," she said.

She closed by presenting a recent photo of her lab team, showing all the students working there. Most of the researchers who do this work are between 20 and 30 years old, she told the students.

"In fact," she added, "most of what you read about scientific breakthroughs in news accounts is done by the same group -- that's you!"

Albreia Hall, a rising junior at Fort Valley State University in Georgia, and part of the summer program, found Bassler's words inspiring. Hall is majoring in biology and would like to go to graduate school. She is studying zebrafish this summer in the laboratory of Rebecca Burdine, an assistant professor of molecular biology. "I like going to the lab every day," Hall said. "I never thought I would say that!"

Program participant Luke Yancy Jr., a rising senior at Morehouse College in Atlanta, learned about the program in November when a few researchers from Princeton visited Morehouse and met with students. Mona Singh, an associate professor of computer science and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton, was there. Yancy, who is majoring in computer science with a minor in mathematics, talked with her about their common interest in computational biology.

"I followed up with her and got into the program," Yancy said.

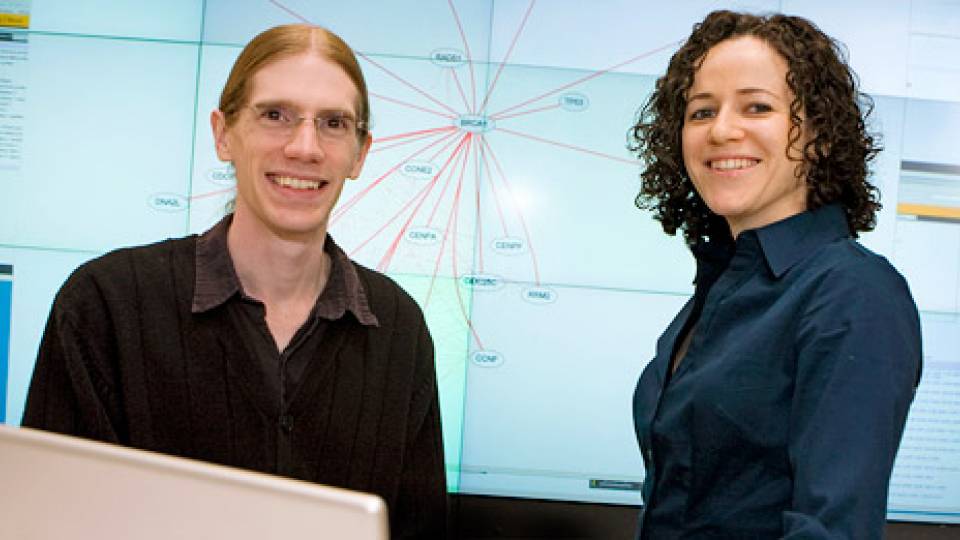

Program participant Luke Yancy Jr., a rising senior at Morehouse College, worked this summer with Mona Singh, an associate professor of computer science and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton. Yancy was charged with developing an algorithm to help Singh's scientific team, which is focused on predicting protein interactions and analyzing protein interaction networks. (Photo: Brian Wilson)

He works this summer with Singh, who is focused on predicting protein interactions and analyzing protein interaction networks. Her lab works on developing and applying algorithms for analyzing biological networks in order to better understand how they work, what certain proteins do and how they interact with other proteins. "This program is a tremendous opportunity for students who want to learn about research," Singh said. "It's a great way of introducing talented students to research, and it can allow them to figure out where their passions lie."

Yancy was charged with developing an algorithm to help Singh's scientific team better predict interactions of particular types of transcription factors known as zinc fingers. Transcription factors are a critical part in cellular networks, as they turn other genes on or off.

Over the course of the summer, Yancy developed an improved algorithm to help identify these zinc finger interactions, and he produced a new graphical tool to help the lab visualize their findings. In order to accomplish this, he had to teach himself advanced versions of several computer languages. The larger topic of finding ways to predict where to look for certain protein interaction sites genome-wide is something he will continue to study."

"One of the major things I will take with me is the ability to dissect and review other researchers' works," said Yancy, who will be applying to graduate programs in computational molecular biology in the fall. "Often, we feel research is an independent adventure by saying things like 'my project.' In Professor Singh's weekly lab meetings, the entire lab constantly critiques and offers suggestions on projects. This feeling of collaboration not only encourages one to keep producing innovative ideas, but allows these ideas to be developed in an environment where it can be nurtured and formed into a groundbreaking project."

Yancy plans to maintain what he calls this "urgent sense of collaboration" as he moves forward with his research career.