Class: "Philosophy of Randomness and Extreme Risk

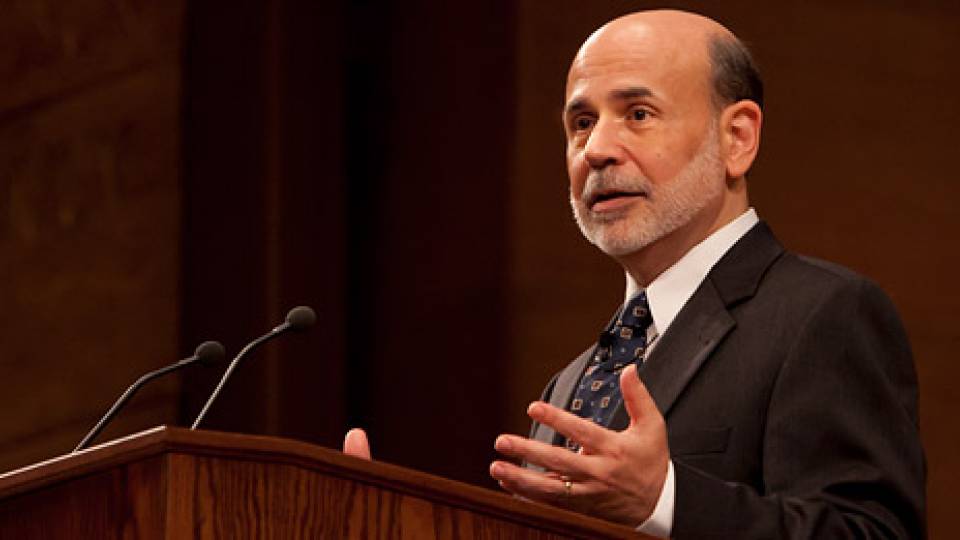

Daniel Cloud, a Perkins-Cotsen Fellow and lecturer in philosophy and in the Council of Humanities, is combining the knowledge gleaned from his first career in finance with his present work as a philosopher to challenge some of the basic assumptions of today's economic system in the class. (Photo: Brian Wilson)

Instructors: Adam Elga, an associate professor of philosophy, and Daniel Cloud, a Perkins-Cotsen Fellow and lecturer in philosophy and in the Council of Humanities. Elga, who received an A.B. in philosophy from Princeton in 1996, returned to join the faculty in 2001 after earning his Ph.D. in philosophy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. An expert in the philosophy of probability, Elga is concerned with the analysis of random phenomena and has made distinguished contributions to various puzzles in epistemology -- the theory of knowledge -- such as his work on what is known as "The Sleeping Beauty Problem." After founding and running a successful hedge fund in the 1990s, Cloud ventured into the academic world, earning a Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University for his exploration of Erwin Schrodinger's theory of the nature of life. Before coming to Princeton in 2007, he studied cancer stem cells at the University of Calgary. He said he wanted that experience, which included many failed experiments, because he hoped it would make him a better philosopher of science.

Description: Pooling their talents -- from the knowledge of economic theories and the philosophy of science, to insights gained from real-life experiences on Wall Street and games of chance like coin spinning -- Elga and Cloud worked over a year to develop this course, their efforts supported in part by the 250th Anniversary Fund. Students are learning the philosophical foundations of methods designed to manage and "tame" extreme risks. In doing so, they are immersed in classical traditions that embrace skepticism and meld humanities, mathematics and the sciences. They are being exposed to modern thinkers who challenge standard economic models and are discussing contemporary risk-management issues that confront policymakers and others who must make safe decisions in risky situations. They are reading selections from an eclectic list, including Manfred Schroeder, a German physicist known for contributions to acoustics and computer graphics; William Poundstone, a popular American business author and skeptic; and Nelson Goodman, the late American philosopher who focused on logic and induction

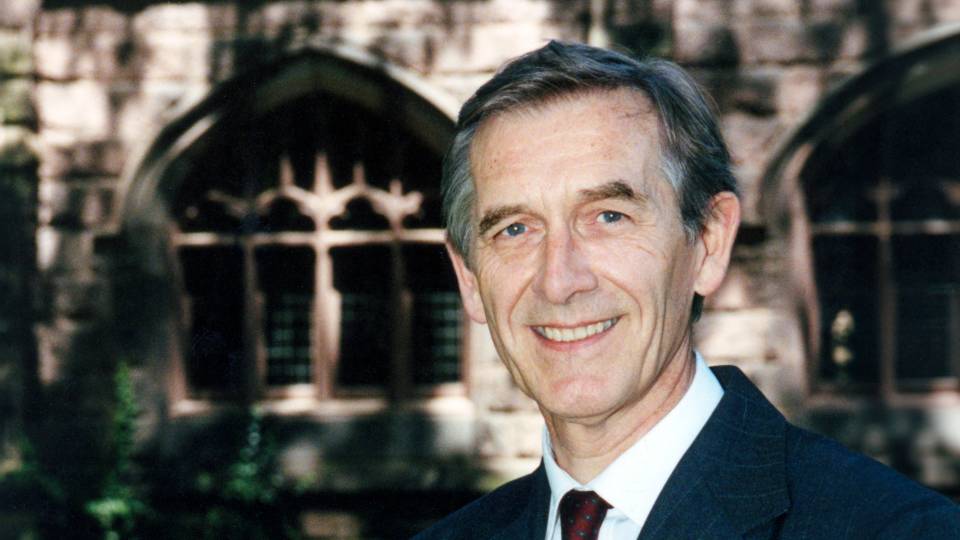

Elga believes many undergraduates arrive at college thinking that there is little place in philosophy for mathematical reasoning. Using "hard edges," such as high-level mathematical analysis, he wanted to draw students with strong quantitative skills to the course. (Photo: Denise Applewhite)

Inspiration: Many undergraduates arrive at college thinking that there is little place in philosophy for mathematical reasoning, Elga believes. Using "hard edges," such as high-level mathematical analysis, he wanted to draw students with strong quantitative skills to the course who, he said, "would actually be very interested in philosophy if they knew the degree to which that kind of thinking played a role in philosophy." Recent financial instabilities in worldwide markets, as well as cascading failures in electrical power grids, prompted him to start thinking about a course that would guide students on how to assess such large problems -- and avoid them in the future. Reflecting on the queries of David Hume, the 18th-century philosopher, Elga said, "It's really about probabilities and about predicting the future -- when you can predict the future and when you can't." Cloud agreed with Elga that, in light of present worldwide financial difficulties, it might make sense to ask, as philosophers have, what is wrong with present societal assumptions. So much of economics, Cloud said, depends on what is meant by words like "rational" and "risk," which are philosophical questions. The two would like to help prepare their students for when they ultimately are in the workforce, likely in leadership positions. "If we teach them to be skeptical about models in some way so that they make a better decision at some point in the future, it may help them and other people," Cloud said. "We hope to produce people who create less risk for the world in doing their jobs."

Some of the lectures take a more whimsical approach. Elga, shown with senior Zachary Slepian, spins coins as part of a demonstration of how small departures from perfect randomness can get magnified over time. A tiny bit of unfairness in a single spin can, over many spins, be magnified to produce massive unfairness, he said, skewing the odds and producing, for example, an inordinate amount of "heads" over "tails." (Photo: Brian Wilson)

Students say: "Princeton has an excellent program in finance, including very strong research in behavioral finance, which does question some of the assumptions of traditional research," said Joshua Harris, a junior majoring in philosophy and pursuing a certificate in finance. "But, by nature, the courses rarely examine or question the most basic elements of the theory: What is risk and how can it be modeled, what is the rational response to risk and so forth."

By focusing on basic questions rather than the development of models, this course, Harris said, "provides a unique and valuable perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of existing approaches. That is one of the most important reasons that I was drawn to philosophy in the first place: the emphasis it puts on analyzing, clarifying and critiquing basic assumptions, techniques and goals. Furthermore, the questions addressed by the course -- of the nature of risk and our response to it -- have wide applications beyond finance: We live in a world rife with risk and uncertainty, and finding sensible and rational ways to think about and deal with these uncertainties is one of the most important goals that we, as individuals and as a society, ought to have."

Sophomore Michael Weylandt is interested in a number of subjects, such as mathematics, philosophy and religion, and was drawn to the course after reading a description online.

"I like a lot of things," he said, so reviewing the universe of course listings offered for any given semester is one of his favorite times of the year. He suspected the class might be fascinating and he has not been disappointed. "This is the sort of philosophy class that I find interesting and rewarding," Weylandt said. "It's focused on real life; not what you might expect from a philosophy class. In this class, we are not asking, 'What does it mean for something to be random?' It's more about how anyone can live in a world of randomness."

Recent financial instabilities in worldwide markets and some other system failures inspired Cloud and Elga to devise a class that would guide students on how to assess such large problems. (Photo: Brian Wilson)