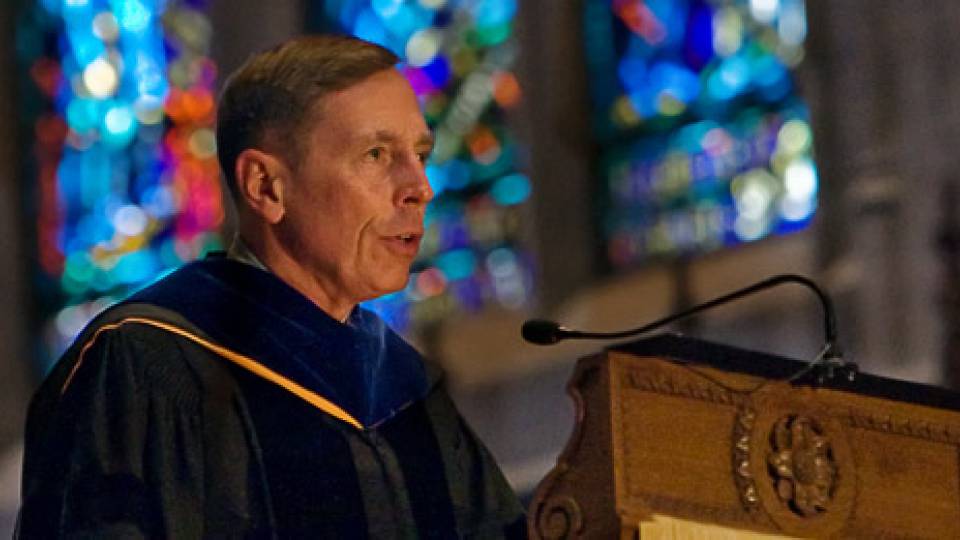

Abridged remarks by U.S. Army Gen. David Petraeus, as provided to the University

Baccalaureate

May 31, 2009

Delivered to the Princeton University Class of 2009

Good afternoon and thank you for that warm welcome. It’s a pleasure to be back at Princeton, an honor to help celebrate the class of 2009’s graduation, and every Princeton graduate’s dream to share a few thoughts with you today!

[Salutations]

Finally, of course, congratulations to the class of 2009! You have worked hard here at Princeton over the last four years. And you should feel rightly proud of all that you have accomplished to get to this day.

But today, with your accomplishments in mind, I would like to do more than just congratulate you; I want to challenge you. For at present, perhaps more than ever before, your communities, your nations, and our world need talented people like you to help tackle the pressing issues we face. So this afternoon, I want to challenge you to respond to this need and to make a commitment to something larger than self, to a greater good . . . to public service.

The Importance of Service

As all here know, ours is a time with no shortage of pressing issues. As unemployment rises, as layoffs mount, as foreclosures stack up, and as federal, state, and local governments steel themselves for budget cuts, routine responses won’t do. As the divide between rich and poor increases in many countries, as preventable diseases like malaria and AIDS take millions of lives, and as basic human rights issues persist, the old ways of tackling problems have become stale. We need thoughtful, hard-working, talented people like you to help find and implement better solutions. We need you and those like you to choose careers in public service and to help solve the many problems before us.

You might suspect that someone who wears a uniform would think of public service solely in terms of military service. And I am very grateful for those who have committed to serve our country in uniform and who have chosen the path of military service.

So let me say thank you to this Ivy League school for proudly supporting its ROTC program and let me offer special congratulations to the soon-to-be commissioned members of the class of 2009 -- Alec Williams, Patrick Gallagher, Cameron Heggi, Brendon Reilly, Jordan Blashek, “Clay” Puryear, Rich Hagner, Katrina Johns, Wyatt Yankus, and Rhodes Scholar and Class of 2009 Salutatorian, Stephen Hammer. Well done to each of you. By the way, Steve, I need your email address. We look forward to seeing you after Oxford!

But while military service is important, it is only one of many forms of public service. Indeed the ranks of Princeton civilians who served in Iraq were led by my great diplomatic wingman Ambassador Ryan Crocker, who was a WWS Fellow. And my first diplomatic partner when we were in Mosul in 2003 was an exceedingly talented WWS grad, Herro Mustafa, who spoke fluent Kurdish and Arabic. They and many other Princetonians and graduates of other great schools helped us turn around a faltering effort and give new hope in the land of the two rivers.

But, of course, public service need not entail putting oneself in harm’s way in foreign countries. While the challenges are different, our own neighborhoods and communities also require creative solutions. Indeed, you can be a servant of the greater good with a private sector career, as well. Our nation’s history is full of examples of captains of industry and masters of the universe who made tremendous contributions of good citizenship. Such individuals represent the best of what John Milton, writing at the time of the English Civil War, called on good citizens to do: actively and forcefully participate in the shaping and the serving and the protecting of society. And in these respects, all graduates can serve and all can contribute.

So whether you follow in the footsteps of diplomats, soldiers, foreign aid workers, health care professionals, educators, entrepreneurs, environmentalists, financiers, legal advocates, or political figures, there are countless ways to serve the public good and numerous issues that would benefit from your focus. But this morning, again, I would like to challenge you to consider a career in public service.

You all have big brains and amazing talents or you wouldn’t be sitting here today. By now you also have a sense of your strengths and, probably, of your weaknesses. And this is the time to ask yourselves: what pressing needs can I help to address?

The Risks and Benefits of Service

Now, as I issue this challenge, I am well aware that it is, indeed, just that: a challenge. Public service is certainly not easy. The sacrifices that it often entails are real…and tough. As I’m sure you’re all aware, it’s possible that you’ll work twice as hard to earn half as much. On top of that, the issues with which you will grapple in public service are difficult, complex, and seemingly intransigent. You will likely face a lack of full resourcing to address those issues. The choices are never easy and the solutions are seldom perfect.

In case all of this reminds you of Dante’s warning: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” let me make clear some of the powerful – albeit less tangible – rewards of public service.

First, the biggest and most important reward of public service is the gratification that comes from being part of worthwhile endeavors. As 1985 Princeton graduate and First Lady Michelle Obama recently said of public service, “There is nothing more fulfilling…

It’s an opportunity to put your faith into action in a way that regular jobs don’t allow…a great way to demonstrate one’s values and to give back to the community.”

Second, public service offers the chance to work hard at work worth doing – what Teddy Roosevelt called “the best prize that life has to offer.” Those of you graduating today already know of this benefit. No one can earn a Princeton degree without a great deal of hard work. So you know personally the satisfaction that comes from achieving a worthwhile goal through hard work. In public service, similarly, there is great reward to be found in grappling with the toughest of problems and in helping find solutions to them.

Third, working in public service, alongside others committed to serving a greater good, fosters an uncommon level of camaraderie and sense of teamwork. There are few more rewarding experiences than linking arms with others in striving to achieve goals that are uniquely challenging and important. Nowhere is this exemplified better than on the battlefield, where troopers routinely put their lives on the line, above all for the troopers on their left and right. The relationships forged between men and women of the brotherhood of the close fight often are the most intense imaginable.

But all forms of public service require shared perseverance in the pursuit of a worthy cause and so offer similar opportunities for camaraderie. Indeed, Woodrow Wilson noted that, in public duty, “There is a reward awaiting you which is superior to any other reward in the world. That is the affectionate remembrance of your fellow men – their honor, their affection. No man could wish for more than that or find anything higher than that to strive for.”

Lastly, public service provides an unparalleled opportunity for relatively young professionals to exercise and develop leadership skills. These skills – faculty, please cover your ears – cannot be taught in the classroom. They come only from experience, from doing, from applying what one learns in an academic environment in real life together with real people. It is, by the way, in that setting that the theoretical “rational consumer” of economics theory and Professor Willig’s lectures becomes the often less than rational citizen of the real world.

In fact, this thought reminds me of an event from the early stages of my career, when I learned firsthand that undergraduate learning has to be complemented with on-the-ground experience. ...

[Humor]

Well, regardless of the truth to that story, I can attest to the fact that I learned the most about leadership from getting my hands dirty and my boots dusty.

Marine Lieutenant Donovan Campbell learned similar lessons following his graduation from Princeton in 2001. He learned how to lead under fire when he deployed with his Marine platoon to help prevent Ramadi, the capital of Iraq’s difficult Anbar Province, from falling into chaos. In his book, Joker One: A Marine Platoon’s Story of Courage, Leadership, and Brotherhood, Campbell recalls how he developed leadership skills while in combat, learning to balance the often competing demands of accomplishing his unit’s mission and taking care of his troopers at the same time.

While, again, the challenges one faces in other forms of public service may not be the same as those on a battlefield, they are no less real and provide ample opportunity to lead. Indeed, young leaders in public service often find themselves entrusted with a level of responsibility that outpaces that of their contemporaries in the corporate world. And there are countless opportunities to develop hands-on leadership skills in a host of other public service endeavors.

So, again, I challenge each of you to pursue a path of public service – not only because the world needs you, but also because doing so will provide you with work worth doing, with unique opportunities for camaraderie, and with considerable scope to develop your leadership potential.

Why You?

“But, why me?” you might be asking yourself. The answer, of course, is that the problems that beset our local, national, and international communities call for public servants who are our best and brightest – and because Princeton has uniquely prepared you for such service.

Your education here has emphasized broad knowledge, critical thinking, and the ability to communicate your thoughts coherently. And the quality and character of such a background are particularly well suited to public service, where the problems are typically complex and the resources thin.

You may be surprised at how the knowledge and skills you have acquired here at Princeton – whether in the social sciences, the natural sciences, or the humanities – will serve you as you serve others.

When I first went to Iraq in 2003, my soldiers and I were often greeted by Iraqis who would say to us: “Thank you, American. We love democracy! What is it?” I also remember being pulled aside after a provincial council meeting by an Iraqi business professor from Mosul University. This was right after I’d given a particularly impassioned and, I thought, persuasive explanation of the virtues of free market economics. “You know, General,” this western-educated professor told me, “the idea of free markets scares 95% of the people in this council.”

In truth, these reactions were not entirely unfamiliar to me because as a graduate student here, I learned to work in an environment in which not everyone thinks the same way as those who come from a military background or from a variety of other backgrounds, for that matter. I was, moreover, aware of the uneven spread around the world of what we know as liberal democratic thinking. So, as we came to grips with the fact that the 101st Airborne Division was going to have to do nation building in Northern Iraq in 2003 -- something for which we were not ideally prepared when we began the fight to Baghdad -- I found myself thinking back to my political philosophy and government classes, and, yes, even to Professor Willig’s Microeconomics course. Given my time here and my later stint as an assistant professor at West Point, I knew how to convey basic ideas about the concepts of market-based economics, the importance of majority rule and minority rights, the idea of basic freedoms, and the need for limits to avoid infringing on the rights of others. I could explain what I knew to the Iraqis we met, and I’d like to think we were all better for it.

You are also uniquely prepared to accept the challenge of public service because, as Princeton graduates, you have been imbued with a culture that values the ideals of service. And in making a decision to serve the public good, you would be guided by the principles you learned here. Recall that it was Princeton President Woodrow Wilson who coined Princeton’s informal motto – in the nation’s service – in a speech he delivered here in 1896. And since that time, our university has expanded the motto to in the nation’s service, in the service of all nations.

These aren’t just words. Countless Princetonians have upheld our university’s motto -- from the Princeton veterans whose service and sacrifice are memorialized by the bronze stars on the windowsills of your dorm rooms, to Wendy Kopp, class of 1989, who wrote her senior thesis about novel ways to attract the best and brightest to teach and then created Teach for America, to some of our nation’s notable modern senators, like Bill Frist, class of 1974, Bill Bradley, class of 1965, Jack Danforth, class of 1958, Paul Sarbanes, class of 1954, and Claiborne Pell, class of 1940. Unfortunately, some of those rival schools to the north have been producing more presidents of late—and I’d ask some of you here today to resolve to change that? But seriously, in rising to meet the challenge of public service, you can take confidence from the fact that each of you will be following in the footsteps of a long line of distinguished Princeton graduates.

You can also take courage in the fact that you have the vitality and energy of youth on your side. Recall the words of traveler and adventurer Richard Halliburton, Class of 1921, who, in his wonderful book, A Royal Road to Romance, wrote movingly about the sense of possibility that he felt as a young man venturing out into the world. “Realize your youth while you have it,” he wrote . . . “Don’t squander the gold of your days. . . . Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you. Be afraid of nothing.”

My mother made me read that book one summer when I was in high school. In truth, I’d much rather have been playing baseball or hanging out at the town pool. Heck, I’d rather have been mowing the lawn than reading that book on some days. But, in the end, I appreciated her insistence. Halliburton told a wonderful tale of the adventures he had after graduating from Princeton as he sought to realize his youth while he had it. And his account of his experiences remains inspirational to this day. So today, in the spirit of Richard Halliburton, I encourage you to be afraid of nothing and to take advantage of your youth in choosing to help confront the challenges that lie before us.

You stand at the threshold of a world of choices with a great education and a wealth of energy. Thousands of Princetonians before you have stood in the same position. Those we often praise most for their impact on our world have chosen the path of public service. They made the bold choice that the hard work of public service was worth it, whatever it took. And, as my mentor General Jack Galvin used to say, “The bold move is usually the right move.” So, be bold and fearless in channeling your energy into the undaunted pursuit of worthwhile work.

Each of you entered this university four years ago with lofty hopes and aspirations. You have achieved a great deal, and you will soon receive one of America’s most coveted diplomas. Whether you have spent these past four years in Terrace or Cottage, Woody Woo or art history, you have much to be proud of, and I offer heartfelt congratulations to you on all of your accomplishments.

As President Tilghman noted, there’s a reason a graduation ceremony is called a commencement not a termination. It’s a beginning, not an end. And, now, our world awaits the impact you will make after your long-awaited walk through Fitz Randolph Gate. Be bold in your commitment to serve. Be determined, not deterred in seeking opportunities to work hard at work worth doing. Good luck, Godspeed, and Go Tigers! Thank you very much.