From the April 6, 2009, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

In a rehearsal room in the Woolworth Center of Musical Studies, students are blowing into their instruments, flicking hands over finger holes, shaking heads, and dipping chins up and down to create different sounds. Playing a few basic recitations absorbs all their concentration, as most in the class first picked up the instrument a few weeks prior and only a handful are experienced musicians.

Classic shakuhachi repertory was an oral tradition. Imprecise scores serve as an outline rather than a prescription.

This immersion into new musical territory is the mission of the course "Masterworks for the Zen Flute: Music for Shakuhachi," in which students across disciplines have the opportunity to play the shakuhachi, a Japanese bamboo flute, and to study its history and culture. The class is cross-listed in the departments of comparative literature, East Asian studies and music, and is co-taught by comparative literature professor Thomas Hare and visiting fellow Riley Lee, the first non-Japanese to attain the rank of shakuhachi grand master.

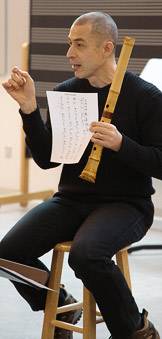

"From the very start, we thought if we were going to do a course on shakuhachi we would have to give the students some hands-on experience," said Hare, the William Sauter LaPorte '28 Professor in Regional Studies.

The shakuhachi traces back in Japanese culture to the eighth century, though its mellow timbre may be unfamiliar to many Western ears. With just five finger holes and no mouth piece, the end-blown bamboo pipe is a simply constructed instrument that can make infinite sounds.

"Learning to play the shakuhachi helps you understand the instrument's role in performance, of course, but it also provides some vantage on social class and social change. It represents one facet of the relation between the arts and Buddhism in traditional Japan and comes to show how these structures in turn have an effect on the music proper," said Hare, who himself began learning shakuhachi nine years ago.

Introduced into the country from China centuries before, the shakuhachi thrived in contemporary Japan, most prominently in the 16th and 17th centuries through its association with Zen Buddhist monks. Shakuhachi means 1.8 feet — the instrument's standard length.

Class lectures are split between Hare discussing the instrument in Japanese mythology, religion, literature and arts, and Lee teaching traditional shakuhachi repertoires through Western and non-Western musicological perspectives. Students also attend weekly music lessons with Lee, an American-born ethnomusicologist who has traveled the world performing and teaching shakuhachi.

Thomas Hare, the William Sauter LaPorte '28 Professor in Regional Studies, discusses how the shakuhachi is represented in Japanese mythology, religion, literature and arts. Tracing back to the eighth century, the shakuhachi represents one facet of the relation between the arts and Buddhism in traditional Japan.

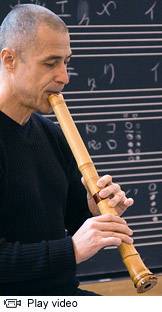

"Of course the students are not going to become superb musicians in just one semester, but they certainly will have a much better appreciation for the instrument than they would if we just talked about it in lectures," said Lee, a Class of 1932 Fellow in Comparative Literature in the Council of the Humanities.

Only a few of the 18 students are music majors, with others representing departments including anthropology, comparative literature, East Asian studies and mathematics.

"It's just one of those classes that you have to take after reading the syllabus," said junior Lauren Ledley, who is not a musician. "It's wonderful to have a teacher like Dr. Lee come from outside the community to expand what you're learning and make it more hands-on."

Ledley, an anthropology major, said learning shakuhachi has helped inform another class she is taking about Zen Buddhism.

Only a few of the 18 students are music majors, with others representing departments including anthropology, comparative literature, East Asian studies and mathematics. "It's just one of those classes that you have to take after reading the syllabus," said junior Lauren Ledley, who is not a musician.

Mathematics major Siddharth Bhaskar said the class builds upon his hobbies playing the tin whistle and Irish flute.

"The shakuhachi is challenging to learn, but it's a lot of fun. Practicing doesn't feel like class work," said Bhaskar, a senior.

During a recent lecture, discussion moved from references to the shakuhachi in Japanese mythology to its place in historical medieval texts, including an early citation to a piece of shakuhachi music in the diary of a Buddhist priest. Hare noted how the piece "Mujô Shinkyoku" — meaning "that single tune which brings the changing heart of things to mind" — shows the shakuhachi's connection to the Buddhist value of transience.

On the following day, small groups of students experienced firsthand the music's changeable nature while learning the piece "Honshirabe." Unlike much Western music, classic shakuhachi repertory was an oral tradition, leading to changes in the music as pieces were passed down and to imprecise scores that serve as an outline rather than a prescription. The only way to learn traditional shakuhachi music, Lee noted, is to hear a teacher play a piece over and over again.

"Notice I came back up on that note," Lee said as he finished playing a phrase for the students to repeat. "It doesn't say that in the notation, but now you know to do that."

With more weeks of insight into the traditional and technical aspects of the shakuhachi, Hare and Lee hope the semester will culminate with a small student recital.

Senior Folasade John said she values the rare opportunity to gain exposure to the shakuhachi and its history.

"I'm not sure I will be so lucky to have this chance again," said John, a comparative literature major and former flute player. "We are learning how to play an instrument many of us would not have picked up without this course and also are getting an experience that we can build upon after we leave Princeton."

Riley Lee, a Class of 1932 Fellow in Comparative Literature in the Council of the Humanities, is the first non-Japanese to attain the rank of shakuhachi grand master. During weekly music lessons, he teaches students how the simply constructed shakuhachi — with just five finger holes and no mouth piece — can be used to make infinite sounds.