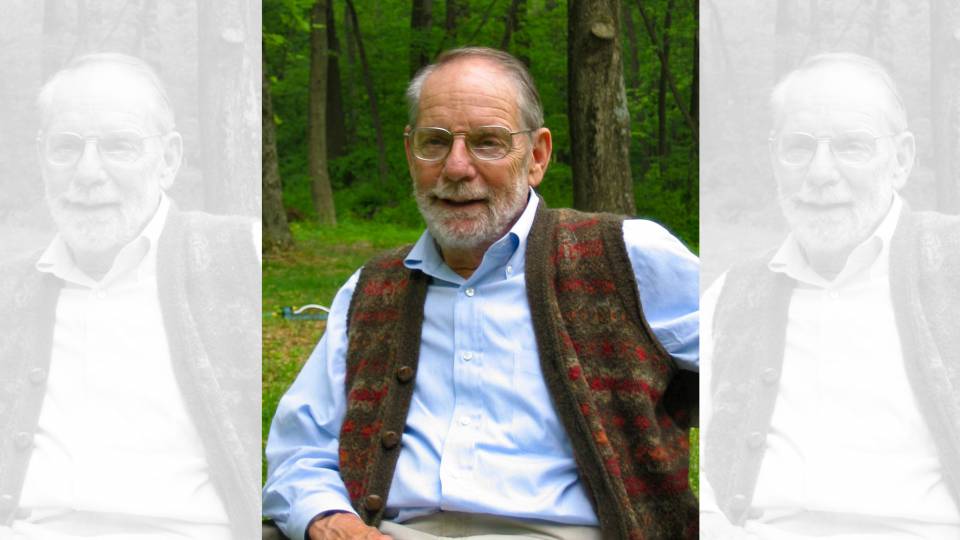

Hugh Price, the former head of the National Urban League, has been a lifelong advocate for civil rights and equal opportunity. Now he's passing along lessons from his 40-year career in education and urban policy to Princeton students.

Price arrived at the University this semester as the John Weinberg/Goldman Sachs Visiting Professor of Public and International Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School. During his five-year appointment, he will teach courses examining how governments, foundations and nonprofit organizations can address social problems.

In addition to serving as president of the National Urban League for nearly a decade, Price has been a vice president of the Rockefeller Foundation focusing on at-risk youth, a senior vice president of the Thirteen/WNET public television station in New York and a member of the editorial board of The New York Times, writing about education and criminal justice.

"Hugh Price is a wonderful addition to Princeton and to the Woodrow Wilson School community," said Anne-Marie Slaughter, dean of the Wilson School. "He brings broad expertise in urban policy, education policy, race relations, children's issues, philanthropy and a host of other issues, as well as the ability to bridge the worlds of policy analysis and practice."

In a recent interview, Price explained how to get communities involved in supporting children who are doing well in school. He also discussed his focus on working with Princeton students to address solutions to social problems from policy and nonprofit perspectives.

From 1994 to 2003 you served as the head of the National Urban League, which helps African Americans secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights. What was the focus of your tenure?

I concentrated on K-12 education because it's clear that the more education you have, the more you're likely to earn and the less the odds are that you'll encounter economic adversity. Many African American children are performing well in school, but quite a few are having severe problems with achievement levels and dropping out.

About a month after I was chosen to head the Urban League — and as I was thinking about how we ought to come at the challenge of engaging in education — I read an article in The Wall Street Journal about a young man who had done well in high school but who was so intimidated by his peers he would not show up at an awards assembly to accept recognition that was going to be bestowed on him. And I just had a visceral reaction that we can't have that. If our children are ambivalent about doing well in school, they are going to be in deep trouble. It struck me that the niche we could fill would be to engage in spreading the gospel of achievement to persuade our children and parents that achievement matters.

How did you do that?

We created a series of activities designed to stoke children's interest in achievement and mobilize communities to recognize kids. And we recognized not just the top achievers but kids who are doing better. We staged block parties, street festivals and back-to-school events to rally the adults around the children. One of our back-to-school rallies in Los Angeles drew 1,200 children. When we inducted 350 African American children into our National Achievers Society in San Diego, Calif., close to 2,000 parents, grandparents and well-wishers attended. At the end of some of these events, we had kids come up and say, in effect, "What took you so long to find me?"

We need to make children who are striving in school our heroes. We do that for teams that win sports championships, for war veterans, for women, for gays and lesbians — we have parades and celebrations for all manner of purposes and people. But by and large communities do not make as big a deal as they need to make about children who are striving to do well, who are making progress and who are doing the right thing with their lives. Those children need company, they need recognition, they need to belong to peer groups that espouse those values and they need protective cover.

Price's book explains how he created a series of activities designed to fuel children's interest in achievement and mobilize communities to recognize their accomplishments.

Your recent book, "Mobilizing the Community to Help Students Succeed," has been distributed to 100,000 educators who are members of the international Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. It outlines how you think every community can take the example of what you did at the Urban League and use it for their children.

Yes, and the beauty of these kinds of initiatives is that this isn't rocket science. This stuff is not hard conceptually. It all depends on the capacity of the community and their willingness to engage. The impetus for these kinds of activities can come from community-based organizations, as was the case with the National Urban League and its affiliates, or it can come from a superintendent or a school board. But it requires an investment of energy and a sustained commitment from the community, which has the capacity to set and reinforce values in our children.

What reaction have you gotten to the book so far?

I am heartened by the response. The National PTA (Parent Teacher Association), for instance, asked me to write an article for its magazine about how local PTAs can help mobilize their communities to motivate kids to learn. I give a speech every other week or so to educators conveying this message. In early September I keynoted the opening ceremony of a school district in Westchester County (N.Y.) to an audience of roughly 300 principals, teachers and administrators. So I'm optimistic that the ideas in my book are gaining traction.

What are you teaching at Princeton?

This semester I'm teaching an undergraduate policy task force on childhood obesity. We'll examine how even when there appears to be broad consensus about the existence of a serious social problem, progress in dealing with the problem is never linear. Students who go into public policy will encounter that very quickly. We'll look at the nature and causation of childhood obesity and examine the ways various sectors have become engaged in dealing with the issue. At the end of the task force, students will produce a report advising a hypothetical incoming chief domestic policy adviser to the president of the United States on what kinds of initiatives to take to combat childhood obesity.

I'm also teaching a graduate seminar that examines whether and how foundations can serve as agents of change. From time to time major foundations have bestirred themselves to do more than respond to proposals — they have tried to change the game by playing a change-agent role. We're looking at some examples of that, such as when foundations helped spawn and expand public television in this country, which worked out well. And we'll look at when it didn't work out well, such as when the Ford Foundation tried to foster school decentralization in New York City in the turbulent late 1960s, which sparked a bitter school strike and racial tensions. We'll examine the lessons learned about what kind of change you can achieve, and what kind of change is risky.

This semester, Price, who also was a vice president of the Rockefeller Foundation, is teaching a graduate seminar that examines whether and how foundations can serve as agents of change. In addition, he is leading an undergraduate policy task force on childhood obesity.

What else will you be doing at Princeton?

These days I'm quite consumed by reacquainting myself with teaching, rolling out two new courses, advising students, promoting my book, and getting to know colleagues at the Wilson School and elsewhere on campus. I'm also winding down my project at the Brookings Institution related to lessons we can learn from the way the military educates and develops young people that could help students who are struggling in school and in life. There's another book idea percolating inside my brain when I have spare time to think about it.

You did some teaching 30 years ago. What is it like being in a Princeton classroom?

I was a visiting lecturer at Yale and Columbia's law schools back in the 1970s. Being in a classroom again is very stimulating. It's given me a chance to think about new issues and new topics. I'm struck by how smart and engaged the students at Princeton are. They're going to keep me on my toes.