Princeton researchers have invented a method for turning simple data about rainfall and river networks into accurate assessments of fish biodiversity, allowing better prediction of the effects of climate change and the ecological impact of man-made structures like dams.

The mathematics behind the new method also can be used to model and predict a wide range of other questions, from the transmission of waterborne illnesses to vegetation patterns on land adjacent to rivers.

The researchers, who published a report in the May 8 issue of Nature, have created a computer simulation that allows them to predict -- based on rainfall measurements and the structure of river networks -- how many species of fish will occupy any given region.

"It is an extremely simple model but it predicts absolutely fantastically well all of the characteristics of biodiversity that we were interested in," said Ignacio Rodríguez-Iturbe, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the leader of the research group that published the report in Nature.

"Our model implies that water dynamics have a commanding effect on biodiversity in river basins."

Paolo D'Odorico, associate professor of environmental sciences at the University of Virginia, called the research "exquisitely original and thought-provoking."

"It is the first study I am aware of that provides a real quantitative framework for the study of river biogeography," D'Odorico said.

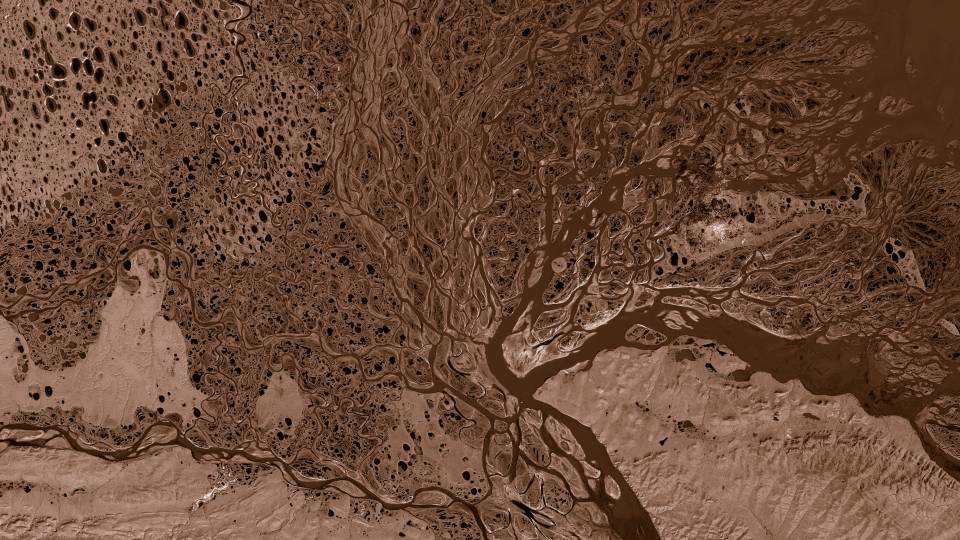

In their research, the authors merged different sets of existing data from the Mississippi-Missouri river basin, an extremely large region that covers more than half of the United States. This network of rivers springs from the Mississippi River, which cuts down the middle of the country. The triangle-shaped basin stretches from Minnesota to Louisiana and from Montana to New York.

Using one set of data, the researchers were able to identify 824 distinct sub-basins and establish how the rivers within each sub-basin were linked together. Another set of data identified 433 different species of fish living in those sub-basins. A third set of data identified each region's average runoff, which is the amount of rainfall that ends up in rivers or streams as opposed to water that is soaked up by the ground.

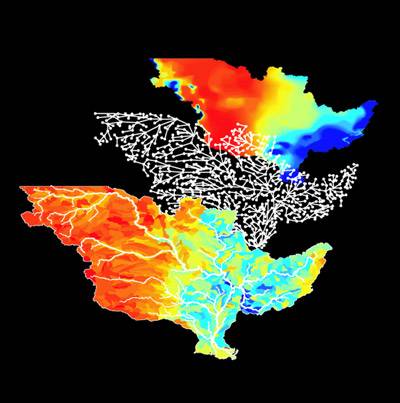

The figure at the top right represents average runoff (the amount of rainfall that ends up in rivers or streams) with the driest regions appearing in red and the wettest in blue. The middle figure is an abstraction of the Mississippi-Missouri river network. The figure in the foreground represents how many different species occupy different regions of the network, demonstrating a close correlation between the average runoff and the number of species. The areas with the fewest species are represented in red; the areas richest in the number of species are represented in blue. (Image: Enrico Bertuzzo, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne)

The researchers combined all these data and came up with a computer model that accurately predicts how many different species of fish will inhabit any given sector of the river basin. Their research shows that the habitats richest in the diversity of species are areas where multiple streams are close to one another.

"This will help identify which parts of a river basin are 'hot spots,' meaning they have more species than others and therefore should receive special care," said Rodríguez-Iturbe, senior author of the paper.

To create their model for the Nature paper, the researchers disregarded the biological features of the fish in question -- for example, which species might be tenacious predators or which might be well-suited to take advantage of available food in the area. The model tracks how many species will thrive in a given area but does not predict which species. It is what is known as a "neutral" model and thus treats each fish equally.

The lead author of the paper is Rachata Muneepeerakul, a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton who received his Ph.D. from the University in 2007. Co-authors are hydrologists Andrea Rinaldo and Enrico Bertuzzo of the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, and Heather Lynch and William Fagan of the Department of Biology at the University of Maryland. The study was funded by the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

"The authors have combined sophisticated ecological theory and sophisticated hydrological theory," said Simon Levin, the George M. Moffett Professor of Biology at Princeton. "This is work not only of practical importance, but [it] also stretches the boundaries of biogeography."

Biodiversity characterizes the number of species within an ecosystem. Biogeography is the study of how biodiversity changes across space and over time.

"If because of climate change you have an increase in rainfall, our model can tell you how that will affect biodiversity," said Rodríguez-Iturbe. "Or if you have a change in the connectivity of rivers due to human activity -- for example, the building of a dam -- our model can also measure how that will affect the numbers and distributions of species."

River networks act as ecological corridors and as such the model will be useful not just for understanding the biodiversity of fish in rivers but also for understanding such things as the dispersal of seeds or even the spread of cholera. Rodríguez-Iturbe, Bertuzzo and Rinaldo also collaborated on a paper that recently appeared in an American Geophysical Union publication on how river networks affect the spread of cholera epidemics.

"Seeds and bacteria are different from fish -- obviously they can't swim upstream," said Rodríguez-Iturbe. "But like fish, their distribution is dramatically impacted and controlled by the river network."

In order to construct the model, the researchers created a mathematical representation of river systems that went far beyond simple volume calculations. They drew upon an advanced area of geometry known as fractals.

River networks are examples of fractals, fragmented geometric shapes whose parts are, mathematically speaking, smaller versions of the whole. Fractals occur widely in nature. For example, the branching structure of trees -- from trunk to branch to twig -- are fractals, as are clouds and lightning bolts and snowflakes.

Unlike in a savannah, where wildlife move across an open plain, in a river basin fish have to move through the fragmented space of river networks, which like all fractals follow a predicable set of mathematical rules.

River networks have "a universal type of structure independent of scale," said Rodríguez-Iturbe. "Some may be big or small, elongated or round, but they all follow some basic features regardless of their scale, regardless of their size, regardless of where they are located in the world."