Neuroscientists at Princeton University have developed a new way of tracking people’s mental state as they think back to previous events -- a process that has been described as “mental time travel.”

The findings, detailed in the Dec. 23 issue of Science, will aid efforts to learn more about how people mine the recesses of memory and could have a wide-ranging impact in the field of neuroscience, including studies of brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

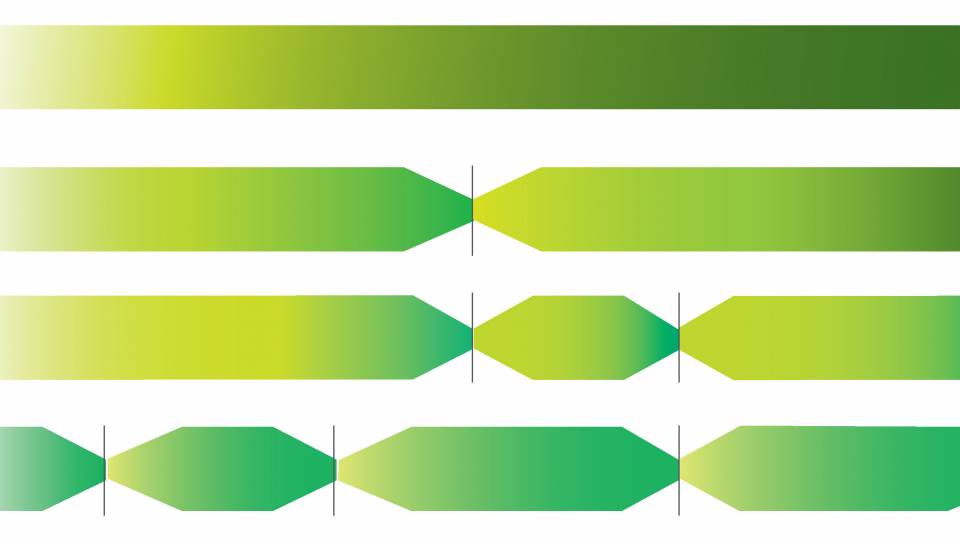

The researchers showed nine participants a series of pictures and then asked them to recall what they had seen. By applying a computerized pattern-recognition program to brain scanning data, the researchers were able to show that the participants’ brain state gradually aligned with their brain state from when they first studied the pictures. This supports the theory that memory retrieval is a form of mental time travel.

In addition, by measuring second-by-second changes in how well participants were recapturing their previous brain state, the researchers were able to predict what kind of item the subjects would recall next, several seconds before they actually remembered that item.

The study was conducted by Kenneth Norman(Link is external), an assistant professor of psychology, and Sean Polyn, who earned his Ph.D in psychology from Princeton in 2005 and is a now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. Polyn and Norman collaborated with Jonathan Cohen, director of Princeton’s Center for the Study of Brain, Mind and Behavior(Link is external), and Vaidehi Natu, a researcher in Norman’s lab.

“When you try to remember something that happened in the past, what you do is try to reinstate your mental context from that event,” said Norman. “If you can get yourself into the mindset that you were in during the event you’re trying to remember, that will allow you to remember specific details. The techniques that we used in this study allow us to visualize from moment to moment how well subjects are recapturing their mindset from the original event.”

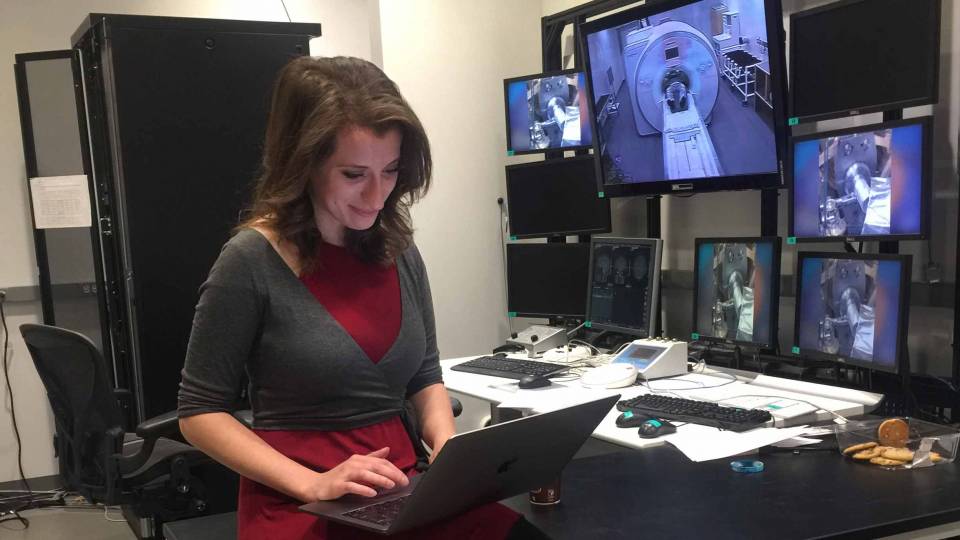

In the experiment, participants studied a total of 90 images in three categories -- celebrity faces, famous locations and common objects -- and then attempted to recall the images. Norman and his colleagues used Princeton’s functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to capture the participants’ brain activity patterns as they studied the images. They then trained a computer program to distinguish between the patterns of brain activity associated with studying faces, locations or objects.

The computer program was used to track participants’ brain activity as they recalled the images to see how well it matched the patterns associated with the initial viewing of the images. The researchers found that patterns of brain activity for specific categories, such as faces, started to emerge approximately five seconds before subjects recalled items from that category -- suggesting that participants were bringing to mind the general properties of the images in order to cue for specific details.

“What we have learned over the years is that what you get out of memory depends on how you cue memory. If you have the perfect cue, you can remember things that you had no idea were floating around in your head,” Norman said. “Our method gives us some ability to see what cues participants are using, which in turn gives us some ability to predict what participants will recall. We are hopeful that, in the long run, this kind of work will help psychologists develop better theories of how people strategically cue memory, and also will suggest ways of making these cues more effective.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health.