From the Dec. 12, 2005, Princeton Weekly Bulletin(Link is external)

The five-year survival rate for women with early-stage breast cancer is 98 percent, according to the American Cancer Society. For those with a late-stage form of the disease, the rate falls dramatically to 26 percent.

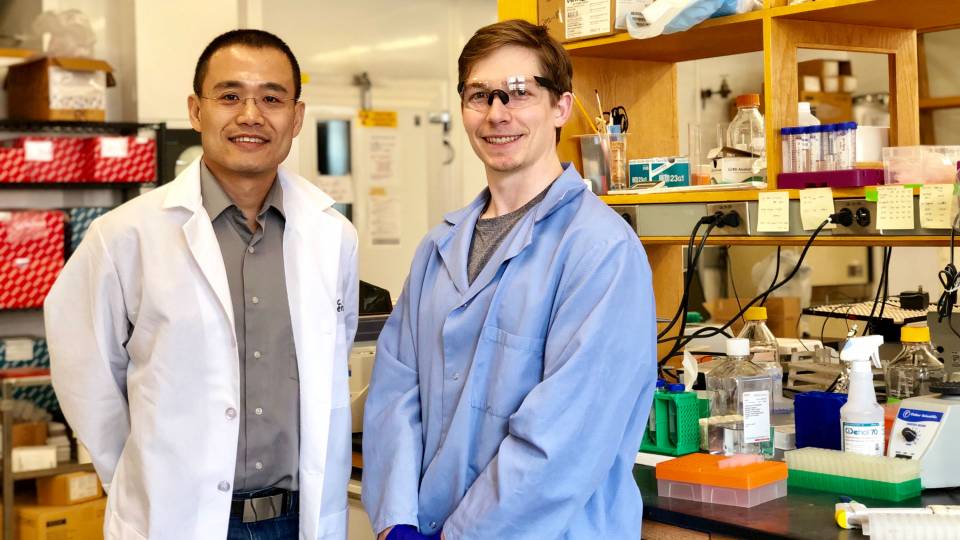

“One reason is that we really don’t know much about metastasis,” said Yibin Kang(Link is external), an assistant professor of molecular biology(Link is external) at Princeton, referring to the recurrence of tumors in secondary sites common in late-stage breast cancer. Armed with a recent grant and innovative research tools, he’s hoping to provide new data on the spread of cancer.

In November, Kang was named the recipient of a $3.8 million Era of Hope Scholar Award from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program. He is one of five scientists in the country to receive the prestigious award this year.

According to the award letter, program officials chose Kang “based upon your record and your potential for accomplishment, with the belief that ultimately your work will accelerate the eradication of breast cancer.” The disease is expected to kill 40,000 American women in 2005; only lung cancer accounts for more cancer deaths in women.

Kang joined the Princeton faculty in 2004 after serving for four years as a postdoctoral research associate at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. He has been conducting research on the molecular mechanisms of cancer metastasis since 2000, and also has received support for his work from the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research, the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation and the American Cancer Society.

Kang said the new grant will provide funds for research that is costly to conduct, and also will help him attract highly competent students and postdoctoral scholars to join his cancer research group at Princeton. “This is a basic science campus — we don’t have a medical school,” he said. “The Department of Defense, however, has emphasized strong support for our approach — utilizing the strengths of Princeton in computational biology, genomics and developmental biology to address this critical problem of cancer from a unique and unconventional angle.”

Kang describes his work as finding a molecular explanation for the “seed and soil hypothesis” — a theory proposed in 1889 by British surgeon Stephen Paget, who sought to determine why certain cancer cells (seeds) grew in certain organs (soils).

“To effectively prevent the spread of cancer, it is very important to figure out what is the property of the tumor cells that allows them to strike in a certain microenvironment,” Kang said. “On the other hand, what is the property of the organ environment that encourages the growth of tumor cells?”

Breast cancer most frequently spreads to bone, then lung, liver and brain. Cancer metastasis is not a random process, Kang explains. Only a small percentage of cells from a given primary tumor can effectively colonize a secondary organ.

He uses experiments with mice to determine how tumors metastasize to bone and other organs. He injects the mice with tumor cells from human cancer patients. The cancer cells have been engineered to express a gene called luciferase — the same gene that makes fireflies glow in the dark. Kang follows the progression of the cells as they form metastases in the mice with an advanced imaging tool that can sensitively detect the bioluminescence signal emitting from metastases.

Once he isolates cancer cells with a particular appetite to invade a certain organ, Kang analyzes the tumor cells through DNA microarray technology, a powerful new tool that enables scientists to quickly establish which genes are expressed at what level in a cell.

Most cells in the body contain a full set of chromosomes and identical genes. However, only a portion of these genes are “turned on” or expressed, and this subset is what gives each cell its properties. Previously, cancer researchers had to tediously search for anomalies such as overexpressed genes in tumor samples one gene at a time. With the help of data processing and mining software, microarray technology allows scientists to determine in a single experiment the expression levels of thousands of genes within a cell.

“We are able to come up with a profile of genes expressed in overly aggressive tumors,” Kang said. “We also look at the genes that are underexpressed because they might be metastasis suppressors.”

Some genes identified in Kang’s experiments encode proteins that allow tumor cells to seek out the target organs efficiently. Other factors secreted by tumor cells destroy bone and promote the formation of new blood vessels. “Through this comprehensive and unbiased approach, we can follow all kinds of molecules that the tumor cell utilizes in order to make the metastasis grow,” Kang said.

Interestingly, some genes used by tumor cells to migrate and spread also are essential for certain normal cell movements during the early development of embryos. “It is as if the cancer cells just pick up some long-forgotten old tricks learned from their early days and use them for an evil purpose,” Kang said. His lab is teaming up with Princeton developmental biologists Trudi Schupbach and Jean Schwarzbauer to investigate this curious link between cancer metastasis and embryonic development.

Kang said he also is taking his research a step further to ascertain whether there are some “master regulators” that activate the spread of cancer. He is collaborating on this project with Sun-Yuan Kung, a professor of electrical engineering who studies signal processing and recognition, and Olga Troyanskaya, an assistant professor of computer science and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics who is an expert in computational biology.

“What is lying behind the metastasis?” Kang asked. “There is always a reason for a gene to be overexpressed or to become hyperactive. It’s likely that there are common mechanisms of control. These are the potential ‘Achille’s heels’ of metastatic cancer that we are trying to find out.”