From the Nov. 7, 2005, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

Seated at a table in Blair Hall on a recent

afternoon, a group of freshmen grappled with the idea of grace. They had just

watched the film “The Diary of a Country Priest,” which gives a wrenching

portrayal of one man’s suffering and his efforts to hold on to, and share, his

faith.

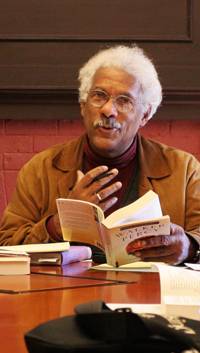

The students are enrolled in the freshman seminar, “Holy Ordinary: Religious Dimensions in Contemporary Fiction,” taught by Albert Raboteau, the Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion. The course focuses on texts that deal with moral and religious values, which Raboteau hopes will resonate with students “concretely and personally.”

Explaining that the appearance of the divine “often is described as a spectacular and miraculous inbreak into this world from another,” Raboteau is offering another perspective by using contemporary texts that present the holy in everyday life.

“I’ve been struck in reading contemporary fiction at how the emergence of the holy is described as occurring within the ordinary events of daily life,” he said. “So it occurred to me that a course in which students could read and discuss some of this literature would be an interesting window on the contemporary vision of experiencing the sacred.”

To get to the heart of such vast and ethereal matters, Raboteau encourages the freshmen to use as their foundation the very intertextuality of literature, which he said is “filled with allusions and direct references to other texts.”

To reflect this, the reading list is wide-ranging and includes several important works of 20th-century and current authors, such as James Baldwin’s “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” William Faulkner’s “The Bear,” Walker Percy’s “Love in the Ruins,” Georges Bernanos’ “The Diary of a Country Priest,” Flannery O’Connor’s short stories, William Trevor’s “Death in Summer,” Mark Salzman’s “Lying Awake,” Manil Suri’s “The Death of Vishnu” and Marilyn Robinson’s “Gilead.”

For Tara Hueston, the books were a major attraction to choosing the seminar. “I love to read, and this seminar gave me a good reason to appreciate many interesting and famous books,” she said. “I have always found the discussion of books fascinating.”

Lisa Bendele also was drawn to the reading list, but she said she was particularly eager to take a freshman seminar that was an “experiment” — which, for her, is studying fiction using religious perspectives.

The discussion that arose from watching “The Diary of a Country Priest,” the 1951 adaptation of the 1937 novel, which the class read before watching the film, provided a powerful means for the students to discover and describe numerous religious allusions and images.

Quickly, as soon as the students agreed on the childlike qualities of the country priest, the conversation expanded to how he could be understood as a Christ-like figure.

“He sort of represents Christ, and he dies young, too,” said Sam Gorman.

“He suffers on behalf of others,” added Hueston. “And he never asks for pity.”

“His death can be seen as an example to others,” said Emmy Stevens.

“There are a lot of images,” interjected Raboteau, “let’s stick with one image at a time.” Here he reminded the class of the loneliness Jesus faced at the Garden of Gethsemane before his arrest. “Just as Christ suffers alone, the priest suffers alone,” he said.

“There’s also his forgiveness,” said Gorman. “He’s shunned by the community but he visits everyone and continues his efforts despite not being wanted.”

“And was anyone struck by the priest’s diet?” asked Raboteau. “Bread and red wine. He’s living on Eucharistic food.”

“That wouldn’t make me feel good,” said Hueston.

“Especially stale bread and bad wine,” joked Raboteau. “But what is suffering in this book?”

“The priest characterizes suffering as need and want,” answered Hueston. “It’s part of being human.”

“He begins to take on the suffering of others,” added Raboteau. “Again, that’s very Christ-like.”

“He’s suffering because he’s absorbing everyone else’s faults,” said Bendele.

Referring to a scene in the film when the priest notices a girl’s apparent suicide letter, even when it is hidden from view, Raboteau added that he was able to “read other people’s hearts,” explaining that this ability is usually “reserved for saints.”

Bringing the class to an end, Raboteau asked the students to listen to “one of the best definitions of ‘grace’” — the song “Grace” by U2. Echoing the final words of the dying priest in Bernanos’ novel—“Grace is everywhere”—Bono’s voice filled the room: “Grace finds goodness in everything.”