Even at a time when multidisciplinary research and teaching are increasingly common, it would be hard to find a course with more contributing disciplines than the latest offering from the Department of Psychology.

“PSY 214: Human

Identity in the Age of Neuroscience and Information Technology,” given

for the first time this semester, has guest lecturers from 13

departments — from classics to computer science, psychology to physics.

The course looked at how advances in science and technology are

changing people’s conception of what it means to be human, and how

these changes are affecting the economy, medicine and many other

aspects of society.

Lecture subjects spanned Aristotle to artificial intelligence. Neuroscientists described how they are coming ever closer to understanding and predicting the workings of the human brain. Computer scientists discussed technology that is muscling in on what once seemed to be uniquely human powers of reasoning. An economist, philosophers, historians and other humanists weighed in on how these advances are affecting the very core of society.

Though the scope of the course may seem unwieldy, the subjects coalesced around the common interest and even a sense of urgency among the participating faculty.

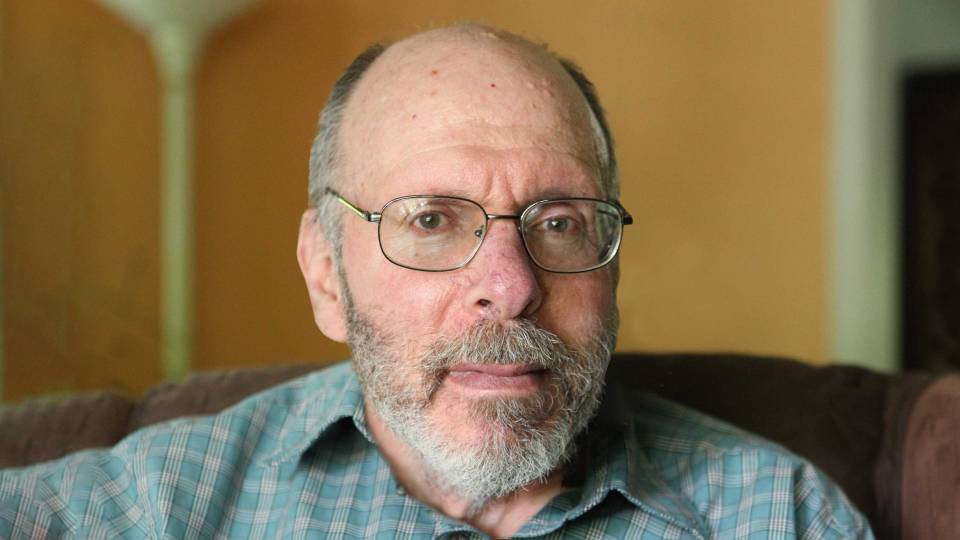

“We are living through a revolution in the way human intelligence is conceived,” said Daniel Osherson, who joined the faculty in 2003 as the University’s first Henry Luce Professor of Information Technology, Consciousness and Culture.

“We think of our identity as depending on a neural tissue lodged in our cranium,” Osherson said. “It’s a different conception than a non-mechanical, non-material idea about a spirit that motivates the flesh. Now it’s an organ we can understand and dissect that moves us.”

Computer technology is further altering that conception, he said. “Just like the Earth was dethroned as the center of the solar system after Copernicus, so human intelligence is being gradually dethroned as the most perfect form of rational processing,” Osherson said.

As big as these changes are, they are not unprecedented. Osherson noted that history has been marked by junctures when the understanding of what it means to be human has been transformed. During the Enlightenment, for example, the idea emerged that people were endowed with rational faculties and that human thought was capable of perfection, Osherson said.

“That contributed to tremendous political developments,” he said. “It was one of the inputs to the political ferment that led to the revolutionary period in Europe. Voltaire and others were writing about this new conception they had of human beings, and ultimately many people decided they could take care of themselves and didn’t need the aristocratic state to do it for them.”

Though it may take decades or centuries to filter through society, the transformations taking place today “may well, judging by earlier historical moments, have momentous consequences for how we decide to organize ourselves, what our relations to one another might be and what we think about a human life,” Osherson said.

An event for faculty

The idea for creating a course to examine these issues came together several years ago when a group of faculty applied to the Henry Luce Foundation to create the professorship for which Osherson was hired in 2003. Osherson, who had been a professor of both psychology and computer science at Rice University, has taught at Stanford University, the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in addition to directing programs in artificial intelligence in Italy and Switzerland. For the year before arriving at Princeton, he came to campus from Texas once a month to develop the course and convene meetings of the faculty members who would participate.

Osherson said he was gratified to find many faculty members who were deeply interested and who gave substantial amounts of time for which they did not receive teaching credit in their own departments. The preparatory meetings and the course itself became a unique opportunity for faculty members to meet and discuss common interests. “People have had a good time attending each other’s lectures and talking about them afterwards,” said Osherson. “So it’s an event for the faculty at Princeton. And it encourages interdisciplinary thinking.”

Ultimately 21 faculty members participated: Charles Gross, Jonathan Cohen, Elizabeth Gould, Deborah Prentice and Osherson from psychology; Robert Schapire and Perry Cook from computer science; Joshua Katz from classics; Leonard Babby from Slavic languages and literatures; Robert Freidin from the Council of the Humanities; Michael Berry and David Botstein from molecular biology and genomics; Gilbert Harman and Alexander Nehamas from philosophy; William Bialek from physics; Bede Liu and Ruby Lee from electrical engineering; Alan Krueger from economics; Michael Mahoney from history of science; Mark Hansen from English; and Philip Pettit from politics.

At a debriefing after the final lecture, many faculty members agreed to participate again, said Osherson, who plans to make some modifications and continue the course next year.

Osherson acknowledged that a format of all guest lectures makes it a challenge to present a well-integrated lesson plan. For that reason, the precepts became an important opportunity to bring together and discuss common themes in the lectures. All precepts were led by Osherson or Adele Goldberg, a professor of humanities and linguistics who also helped organize the course.

“We drew out themes and refined points in the lectures and let the students do a lot of the talking,” said Goldberg. “The students were wonderful. They got the big picture. They dug into the specific ideas.”

For students, the course was not only a fascinating whirlwind through subjects of neuroscience and information technology but a chance to indulge their own eclectic interests. “There are so many amazing professors at Princeton, and you can only take so many classes,” said sophomore Elizabeth Distefano, who is considering a major in economics or molecular biology and possible certificates in finance, neuroscience, Spanish or Italian. This class “let someone like me hear from lecturers in areas like metaphysics, philosophy, linguistics and music, which are areas that I otherwise wouldn’t have heard any lecture on.”

Emily Aull, a freshman, said the experience will help guide her choice of courses in the coming semesters. “Nearly everything I learned in the course was new and eye-opening,” she said.

In one precept, Osherson followed up on his own earlier lecture, which addressed fundamental differences between human intelligence and machine computing and asked the question, “Are our computers doomed to stupidity?” He walked the students through a clever and somewhat technical proof that a computer cannot be made to compute every mathematical function.

Moving from the technical to the philosophical, the final two lectures were delivered by Nehamas, the Edmund Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor in the Humanities, who spoke about “Conceptions of a Life Worth Living.” As science and technology bring new possibilities for how we live our lives, what values and goals should we pursue, he asked. Nehamas touched on research published in December by Princeton’s Alan Krueger and Daniel Kahneman (see story on this page) seeking a national index of well-being, but drew his deepest conclusions from the ancient philosopher Aristotle. The definition of happiness, Nehamas argued, must come from more than an individual’s subjective sense of whether he or she is happy, but must include an objective measure of how well a person is taking advantage of their abilities and circumstances to reach their full potential.

Such confrontation of age-old questions and new technologies are part of what the course is all about, said Goldberg. “We have new tools and old questions,” she said. “That is one of the most exciting times in science.”

Departments involved in PSY 214:

Classics

Computer science

Council of the Humanities

Economics

Electrical engineering

English

History of science

Molecular biology and genomics

Philosophy

Physics

Politics

Psychology

Slavic languages and literatures