In his new book about time travel, astrophysicist Richard Gott has plenty of science to explain, but first he makes sure that his readers are up to speed on science fiction.

The first chapter of "Time Travel in Einstein's Universe" walks readers through the wonders and conundrums of time travel as illustrated by books such as H.G. Wells' "The Time Machine" and the popular movie "Back to the Future."

One section is titled "Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure and Self-Consistency," referring to the popular 1989 film about two high school students who travel through time to earn a good grade on a history project.

It's not just a trick to engage readers in a technical subject. Gott shows that science fiction writers have been surprisingly prescient in exploring ideas that have proven to be topics of serious investigation among scientists. Gott, in fact, has used ideas from time travel research to develop a novel theory about the origin of the universe.

As Gott discusses the idea of warp drive from the television series "Star Trek," he builds the case for one of his central themes: Time travel is not just the stuff of fantasy fiction. Although time travel on any significant scale would require a great deal of effort, it is physically possible, he writes.

"We have had time travelers already," Gott said in an interview at his Peyton Hall office. "The greatest time traveler so far is (cosmonaut) Sergei Avdeyev, who, by virtue of being on space flights for 748 days, is one-fiftieth of a second younger than if he had stayed home. So that man has traveled one-fiftieth of a second into the future."

The key to time travel of any sort is the bendable nature of time, as described by Einstein's theories of relativity. "Einstein showed that moving clocks tick slowly," Gott explained. Moving at typical, earthly speeds, all clocks tick at essentially the same speed, with differences detectable only by extremely accurate atomic clocks. But for anyone able to approach the speed of light, the passage of time slows dramatically.

So astronauts could speed through space for what they believe to be a few years, but then return home to find that time had advanced many, perhaps hundreds of years.

"I suspect that in the near future, we'll see more time travel into the future, but only in small hops," said Gott. "It just depends on how much money we are willing to spend on the space program."

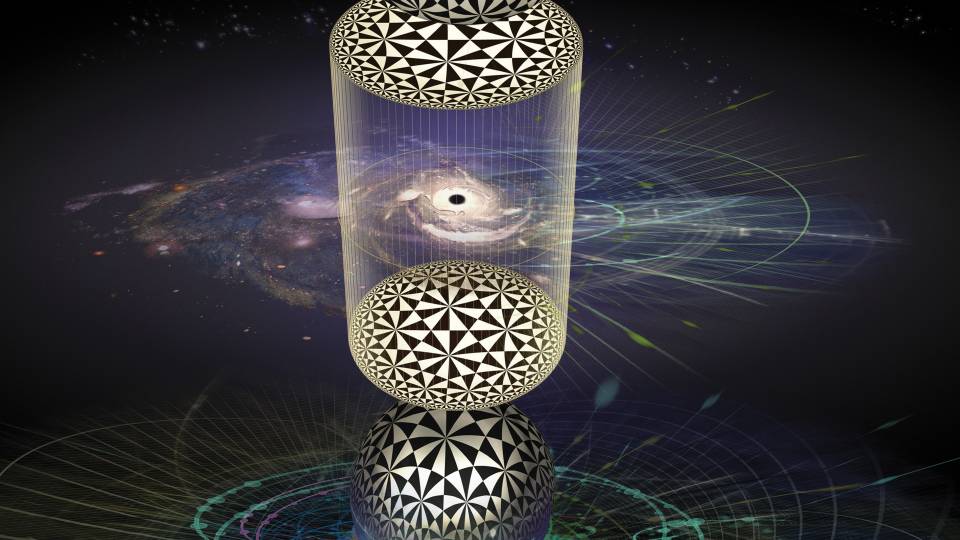

Regarding time travel into the past, Gott said it may be possible, but much more difficult. One idea, developed by Kip Thorne and colleagues at the California Institute of Technology, involves "wormholes," which are shortcuts from one part of the universe to another. The other, which Gott proposed in 1991, involves two "cosmic strings," which are filaments of very dense matter left over from the early universe. When two cosmic strings pass each other at a great enough speed, someone traveling around the strings would be transported back in time.

"Time travel to the past is a project that only supercivilizations could attempt, because it involves manipulating enormous masses," Gott said. To use the cosmic string idea to travel back one year, for example, would require a time machine with half the mass of our galaxy. Investigating both approaches may also require an understanding of quantum gravity, an area of physics that has not yet been developed, Gott said.

Such requirements, however, should not stop people from thinking about time travel, Gott said. Science fiction writers often have used mechanisms that seemed outlandish at the time, but then became part of standard physics, he noted. H.G. Wells, for example, wrote "The Time Machine" in 1895, when time was still thought to proceed at a fixed and universal rate; 10 years later Einstein published his theory of special relativity, which showed that the progress of time changes according to the circumstances.

In addition, the study of time travel "pushes us to explore physics in extreme limits and to test the boundaries of the laws of physics," Gott said. In his own case, Gott and Princeton graduate student Li-Xin Li used their research into time travel to develop a possible explanation for the origin of the universe. The two showed that the early universe could have branches -- essentially new universes branching from an original trunk -- and that one of these branches could form a time loop that circles back and grows up to become the trunk. "This is a model that allows the universe to be its own mother," said Gott, noting that it also solves some nagging problems associated with the start of the universe.

Another reason for studying time travel is that it is an effective tool for teaching. In his book, Gott gives an accessible explanation of Einstein's theories of special and general relativity. These theories often come up in the introductory astrophysics course, "The Universe," which is geared toward non-scientists and is co-taught by Gott, Neil Tyson and Michael Strauss. Gott also teaches an entire junior/senior-level course on general relativity, which he said is not commonly included in undergraduate programs.

"Einstein was named the person of the century by Time magazine -- I think it's important to know what he did and how he made his discoveries," said Gott. "And time travel is a very interesting window from which to look at special relativity and general relativity."

So would Gott be willing to experiment with time travel if the opportunity presented itself?

"I certainly would be interested in going a couple of hundred thousand years into the future and seeing what had become of the human race, if it had survived and, if so, what people were up to," he said.

Even if he couldn't come back?

"Yes. If you took a trip a thousand years into the future -- with reasonable acceleration -- the time aboard your space ship would be 24 years. That is exactly the amount of time that Marco Polo spent in his travels," he said. "I think it would certainly be equally, if not more, interesting to see the world in the year 3000. It would be worth the investment of 24 years. Even if you couldn't come back."

Contact: Marilyn Marks (609) 258-3601