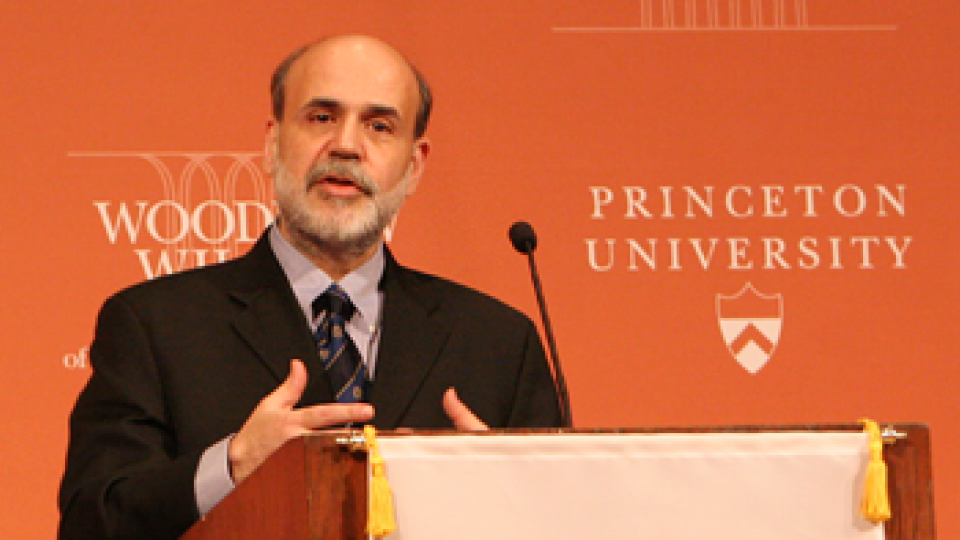

If the economy slides into recession, Professor Ben Bernanke will be among the first to know.

Bernanke, chair of the Princeton economics department, is the rookie member of the business cycle dating committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a six-member group that decides when the U.S. economy has entered or exited from a recession. A private nonprofit organization founded in 1920 to support nonpartisan economic research, the NBER has long been the nation's best recognized authority on business cycles.

Since he was appointed to the post in July 2000, Bernanke has added another responsibility to his schedule: being on call to attend a meeting called by the committee chair, Stanford University's Robert Hall. That usually means one thing: bad news.

"We see each other all the time," Bernanke said of the committee members, "but a formal meeting usually leads to a declaration that the economy's in a recession."

For now, at least, he does not expect the committee chair to phone. The economy is slow, he believes, but not bad enough to be considered in recession.

"We've had a major slowdown that's come about because the economy over-invested in high-tech," he said. But he suggested that the rest of the economy is not doing so badly, and that tax cuts and recent interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve Board should give it a boost.

"Much of the non-high-tech economy is still reasonably healthy -- because consumers are still spending well, because housing has done, in fact, relatively strongly," Bernanke said. "I personally would have preferred if the Fed had been a little less aggressive, but given what they've done, and given the tax rebates, that certainly increases the odds of the second half of the year being a little stronger."

"I think there's a good chance we'll dodge the bullet this time," he said.

Not surprisingly, the business cycle dating committee doesn't meet very often. The group last met formally in April 1991, when it announced that the economy had entered a recession the previous July. As it happened, the recession already had ended a month before the announcement. (At eight months the last U.S. recession was short; recessions since 1945 have averaged 11 months).

When they get together, the group does not work to forecast a recession, but to review economic data to determine if one already has begun. Committee members consider a variety of economic indicators, including the industrial production index, housing starts, inventories, and employment indicators such as overtime and hours worked.

The committee also reviews gross domestic product (GDP), but doesn't follow the textbook definition of a recession -- two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. "There are many dimensions to economic activity," Bernanke said, "so looking just at GDP is not necessarily accurate. Other problems with relying solely on GDP are that it is a quarterly rather than monthly indicator, and it is often subject to large revisions as new information comes in over time."

The need for this variety of data means the announcement of a recession often comes six months or more after it has already begun. "We don't want to call it and have to change our minds," Bernanke said. "We're not out there trying to anticipate or be ahead of the curve."

Still, not everyone thinks the dating committee should continue its practice. "There are some economists who think these dates aren't really needed or even all that meaningful," Bernanke noted.

So why do it? Dating recessions can be useful for economists doing certain kinds of research and modeling, Bernanke said. He added that historians and others also consider recessions a convenient way to divide and mark history -- they separate good times from bad and help show the progress of the economy.

Recession-dating traces its roots to NBER founder Wesley Mitchell, who did classic work on the business cycle alone and in collaboration with Arthur Burns (later the chair of the Federal Reserve Board under President Nixon). The NBER has retrospectively dated U.S. business cycles month-by-month going back to 1854. Besides its work in business cycles, the NBER has branched out to study a wide range of economic issues and has hundreds of leading academics as research associates.

Bernanke will serve on the committee for as long as he remains director of the NBER's Monetary Economics Group -- an indefinite appointment.

Contact: Marilyn Marks (609) 258-3601