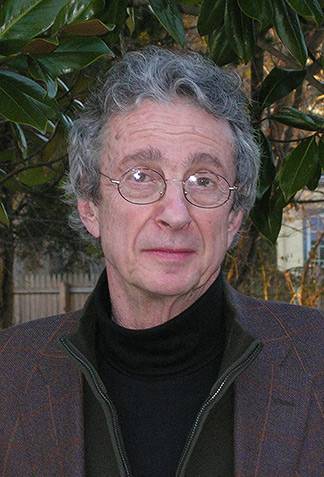

C.K. Williams, an acclaimed poet and faculty member at Princeton University whose writing embraces the full breadth of the human experience, died Sept. 20 of multiple myeloma at his home in Hopewell, New Jersey. He was 78.

Williams, a former lecturer with the rank of professor in the Council of the Humanities and the Lewis Center for the Arts' Program in Creative Writing, joined Princeton in 1995 and retired on July 1, 2013.

"He was a great poet, one of the few who still believed that poetry can indeed have an impact in the world," said Paul Muldoon, the Howard G.B. Clark '21 University Professor in the Humanities and professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts.

Williams, whose work often highlights war, politics and social injustice, won virtually every major writing award in the field of poetry throughout a career that spanned six decades. "Repair" was awarded the 2000 Pulitzer Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award; "The Singing" won the National Book Award for 2003; and "Flesh and Blood" received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1987. Other books of poetry include "Wait," "Collected Poems," "Writers Writing Dying" and "All at Once." His most recent collection of poetry, "Selected Later Poems," was published Sept. 22. His most recent book of essays, "In Time: Poems, Poets, and the Rest," was published in 2012. He completed another collection of poems, "Falling Ill," before his death.

Williams published translations of Sophocles' "Women of Trachis," Euripides' "Bacchae" and poems of Francis Ponge, among others. He also wrote a memoir and two children's books.

At Princeton, Williams taught creative writing, introductory and advanced poetry, dramatic adaptation, and literary translation including "The Art of Imitation: Translation in Theory and Practice," co-taught with Sandra Bermann, the Cotsen Professor of the Humanities, and "Translation and Adaptation for the Stage," co-taught with Michael Cadden, chair of the Lewis Center and a senior lecturer in theater.

"You never had to guess where Charlie stood on a piece of work," Cadden said. "In most classes, he ranged all over the place, emotionally and intellectually, in relation to our students' work. It could make for a wild ride.

"His pedagogical generosity took the form of absolute honesty, expressed sometimes with laughter, sometimes with fury, sometimes with boredom," Cadden said. "It was clear to the students that he had the highest expectations about the work they could produce, and they did all they could to live up to those expectations."

Cadden added that his favorite fact about Williams — who was born Charles Kenneth Williams in Newark, New Jersey, in 1936, and grew up in South Orange and the suburbs of Philadelphia — was that the comedian Jerry Lewis was one of his childhood babysitters.

Williams served as an adviser for hundreds of students during his time at Princeton, including Chenxin Jiang, a 2009 alumna who remembers Williams as a great teacher and mentor as well as a gifted poet.

She said taking Williams' class on translating poetry as a sophomore "shaped the rest of my Princeton experience as well as my subsequent career. CK taught us to love translating as a way of reading poetry, weighing the words in each line." On the last day of that class, Williams asked Jiang to stay in touch with him, and over the next year, while studying in England, she sent him a poem each week, translated from Chinese, Italian and German. "He read it promptly and sent me thoughtful, line-by-line comments," she said.

Jiang said getting her creative writing thesis — a translation of the work of a young German poet — published in literary magazines launched her career in literary translation; this year, HarperCollins will publish her first translated book.

Another advisee, Amy Paeth, a 2008 alumna, also remembers Williams as a mentor. "His poetry workshops were the most formative courses of my Princeton experience," said Paeth, a lecturer in critical writing and English at the University of Pennsylvania. "He expected his students to be or become his intellectual peers. Praise didn't come easy: we were real poets. The discerning critic was shrewd, but also joyful."

Adrienne Raphel, a member of the Class of 2010, said she was lucky to work with Williams in poetry and translation workshops. "No weak image or wimpy phrase slipped by his sharp gaze — his intuition was sometimes terrifyingly blunt, but always brilliant and always impeccably sharp. Williams taught me about honesty in poetry. Whatever a poem is going to say, it has to be true," said Raphel, a doctoral candidate in English at Harvard University.

Williams began his undergraduate studies at Bucknell University, having been recruited for basketball — he stood six-feet-five-inches — but later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania. When he decided he wanted to be a poet, he dropped out to live in Paris, but returned to school several months later and graduated in 1958. He then attended Penn's graduate writing program but did not finish. Poetry magazine first published his work in 1964 and his first book of poetry, "Lies," was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1969, at the urging of Anne Sexton, whom he met at a poetry reading.

Before coming to Princeton, he taught at the YMCA in Philadelphia in the mid-1970s, then at Drexel University, George Mason University, and Franklin and Marshall College.

In addition to the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, Williams' fellowships and awards number in the dozens and include the 2005 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, which includes a $100,000 award; a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1974; the PEN/Voelker Career Achievement Award in Poetry and the Berlin Prize from the American Academy in Berlin, both in 1998; and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Literature Award in 1999; among others. He served as editor of several poetry and essay collections.

His work sifts through the experiences and observations of everyday life, catching the details that can so readily lead to the big questions about life and the big emotions of love and despair. The 40 poems in "Repair," for example, focus on hurt and healing, while exploring such themes as love, memory, social disorder, the natural world, the Holocaust and American race relations. When his memoir, "Misgivings: My Mother, My Father, Myself," was published in 2000, he told the Princeton Weekly Bulletin, "What inspires me now are tensions, social and personal, and the movements of language which promise to take me places I haven't yet been."

His work gained early renown in the late 1960s for its vehemence against the Vietnam War and its moral reflection of the Civil Rights movement. His poem "In the Heart of the Beast," about the killing of student protesters at Kent State and Jackson State universities in 1970, begins: "this is fresh meat right mr nixon?"

At that time, Williams wrote in an urgent style, using short lines and minimal punctuation to project his anger about the war. Gradually, over the next decade, Williams began to write poetry with longer lines, a signature style that at times garnered both favorable comparisons with Walt Whitman and criticism for being too much like prose.

In fact, Williams wrote a study of Walt Whitman, "On Whitman" (2010), part of the Princeton University Press series "Writers on Writers."

"Everyone, including Charlie, has noticed the affinity of his poetry to Whitman's, both in its long line and its largeness, its inclusiveness, the way it can rise to the prophetic in a way that contemporary poetry seldom does," said James Richardson, a professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts. "But the core of his work is something far more personable, absolutely life-size. It's a voice speaking to you, just you, across a small table, thoughtful and tender, excited and vulnerable. It says everything you hadn't quite thought of, or weren't quite ready to say aloud."

Richardson said that Williams treated everyone, colleagues as well as his students, as the same age. "He was always at your level. Well, metaphorically anyway: actually he was about a foot taller than I am, and our hugs were a little incongruous. When we sat down to dinner with him, there was always his piercing friendliness."

While his poems may depict the tiniest details of life from the viewpoint of a careful observer — a toddler tripping, a woman showing a bug bite on her arm — larger themes of war and politics dominate much of his work, such as the two poems "War" and "Fear" in "The Singing," which examine the events of 9/11 and their aftermath. In the last decade, the threat of global warming also has permeated his work.

Yusef Komunyakaa, a professor in the creative writing program at New York University who taught at Princeton from 1996 to 2006, first met Williams in 1978 as a student in his graduate poetry workshop at the University of California-Irvine. "C.K. taught us to listen as an American to the everyday music in human experience," Komunyakaa said.

When he arrived at Princeton, Komunyakaa said he wanted to convey to Williams how much he influenced his life. "But it was much later, one night in Paris in 2007, I said, 'C.K., thanks for giving me the confidence early on.' Of course, C.K. being C.K., he only smiled and said, 'Bullshit. Do you want another glass of wine?'"

Williams and his wife, Catherine Mauger, a jewelry designer and native of France, divided their time between his home in Hopewell and a house in Normandy. The two met by chance at an airline ticket counter when their flight was delayed.

Williams remained a strong presence at campus events even after his retirement. In conjunction with "Myth in Transformation: The Phaedra Project," which spanned the 2013-14 academic year, students performed a staged reading of Williams' new play "Beasts of Love" — which focuses on the brutal aspects of Phaedra's love for for her stepson Hippolytus — at the Princeton University Art Museum.

Williams' last public appearance at Princeton, on March 9, 2014, was a recital for the Princeton University Concerts (PUC) series that featured Williams reading from his work accompanied by renowned pianist Richard Goode playing works of Schumann, Mozart, Chopin and others.

Marna Seltzer, director of Princeton University Concerts, said she will never forget the concert, which she arranged after having met Williams at a luncheon at Prospect House and learned that he studied piano as a child and loved classical music.

"Charlie shared so many personal poems, including one that he wrote for the occasion based on Beethoven. There was an intimacy in the hall, and a feeling that we were experiencing not a performance, but the outpouring of two intimate friends who were sharing their most personal utterances. After that concert, Charlie loved to attend Richard's recitals in Paris during the year.

"Last spring, Charlie remained involved with PUC. He sat on the final jury for our Creative Reactions [classical music essay] contest and was a spirited and committed judge. Charlie was a quiet but powerful presence," Seltzer said.

In addition to Mauger, Williams is survived by a son, Jed; a daughter, Jessica Burns, from his first marriage; son-in-law Michael Burns; a sister, Lynn Williams; a brother, Richard; and three grandchildren. Also among his surviving relatives is his first cousin N. Jeremy Kasdin, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, and vice dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Princeton.

Donations may be made to Children of Uganda, P.O.Box 659, Charles Town, West Virginia, 25414, or online.

A memorial service will be held at the University at a later date.